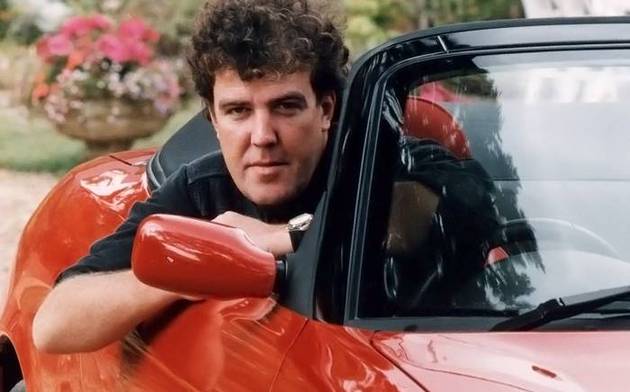

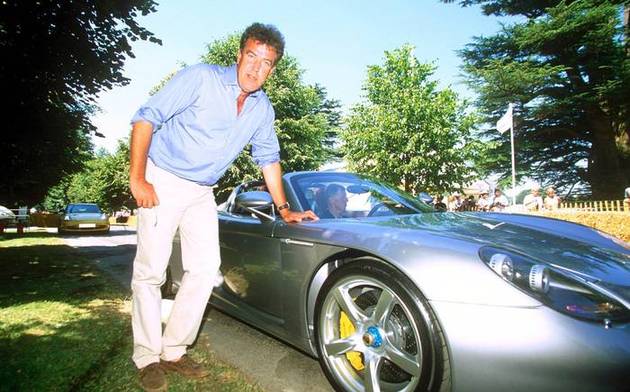

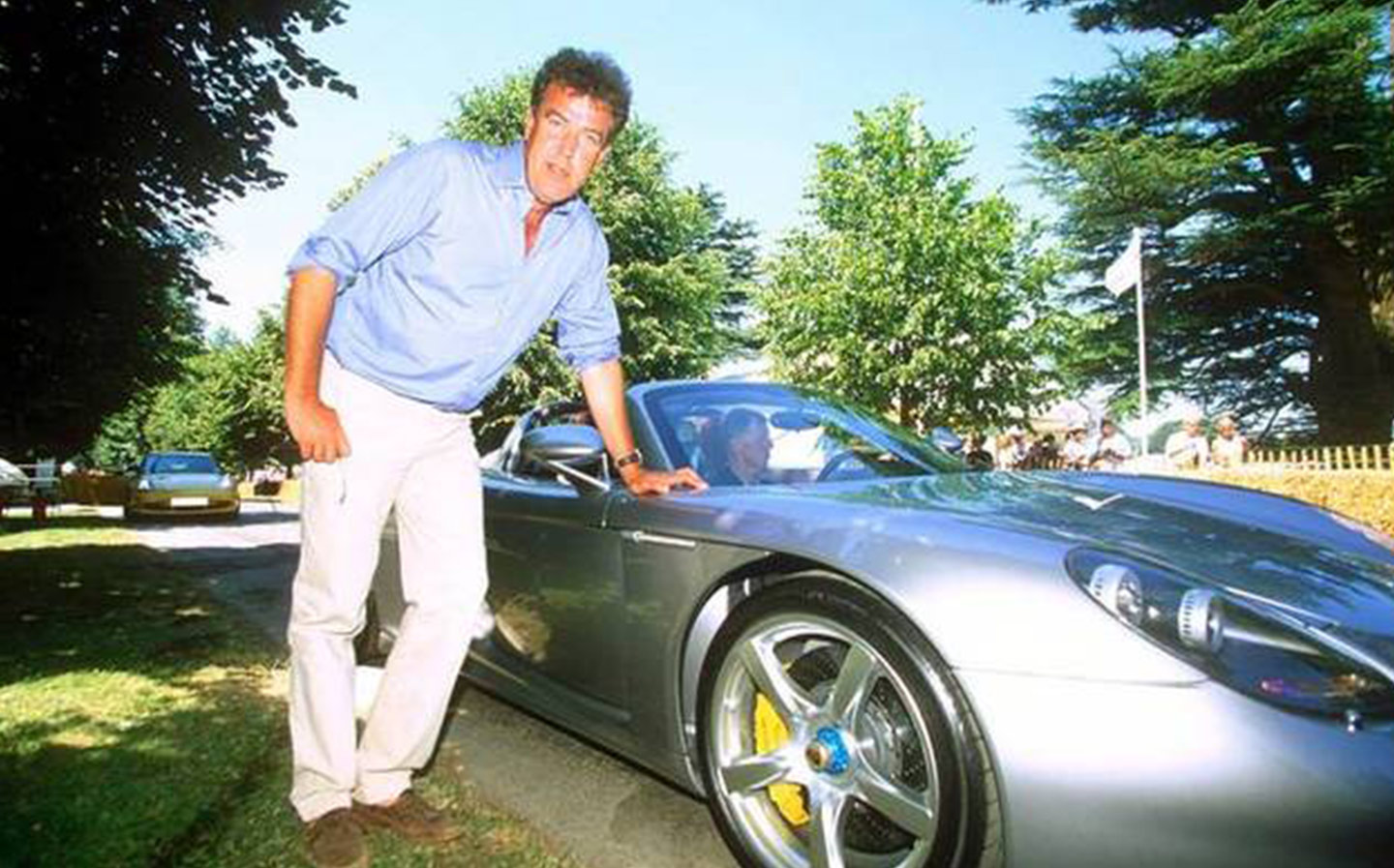

When Jeremy Clarkson attended the first ever Goodwood Festival of Speed (1993)

Winning formula

This article was first published in The Sunday Times on June 27, 1993

Ordinarily, if you go to a motor race, you will find yourself among a great many fat people in anoraks, knee-deep in half-eaten beefburgers and at least 50 yards from the nearest racing car.

While the horse racing fraternity has Ascot, sailors have Cowes and oarsmen have Henley, motor racing has, since the 1930s, had no equivalent. The oikish image of the sport has grown even worse in recent years. Ever since Nigel Mansell’s yobbish antics during the National Anthem became a familiar television spectacle, Silverstone, Brands Hatch et al have been attracting a new breed of builder’s-bottomed spectator, can of lager in one hand and Union Jack in the other.

Now, however, there is the Goodwood Festival of Speed, and motor racing is up there once again with Wimbledon, Cowdray, Ascot and Henley.

It’s a family day out, so long as the family in question consists of two daughters whose names end in the letter “a”, a father in a blazer, and a mother in floral trousers. It’s a day of sultry sunshine and Pimm’s, of tartan rugs and picnic baskets. It’s where showbiz mixes with high-octane fuel in a cocktail of sunshine, strawberries and screeching rubber.

The plan was a simple one. Lord March simply decided to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps and hold a hill-climb in the grounds of Goodwood House, his Sussex home.

The rules would be very simple. The rich and the famous would be invited to bring along their old cars and blast them up the 1.1mile drive as fast as they liked. Electronic timing would provide an element of competition.

1993: the year in cars

- In its first year, the Cones Hotline leads to the removal of just two sets of traffic cones. Drivers used it to report lanes that were needlessly coned off. It was scrapped in 1995.

- Hitch-hiking guidelines are cut from the Highway Code. Speed bumps and 20mph limits are in.

Now, these old cars were not your average run-of-the-mill Allegros. A quick glance through the 100-strong entry list revealed a welter of Ferrari 250 GTOs, each of which would fetch £2m, more Aston Martins than the company chairman Walter Hayes thought they’d made, and historic racing cars by the bucketful. Quite apart from some ex-Nigel Mansell and James Hunt Formula 1 cars, there were two BRM V16s, which have been described as the noisiest cars ever made (they are), a thin-walled Vanwall and, the fastest of all of them in practice, a Maserati 250F.

These motoring milestones were not only on show in the paddock, but also being driven as intended, hard and fast; some would say too hard and fast.

It was supposed to be a fun day out, but as one driver said: “When you get to the start line and put your visor down, I dunno, you just get all worked up. There’s this sort of red mist that comes down.”

Anyone who claims that the recent roller coaster of classic car values has rendered such machinery uninsurable, undriveable and fit only for a museum should have been there. There were spills, and thrills, and, sadly, even a death.

If you were really only there for the sounds and the smells and the notion of being at an event sponsored by, among others, Aston Martin, Hackett and Veuve Cliquot, there was plenty of more gawp-worthy material.

The paddock was like a page from Hello! No doubt one day it will be.

George Harrison piloted his own motorbike, part-car called the Rocket, and later was to be found telling designer Gordon Murray how much fun it had been.

Rowan Atkinson, complete with wife, linen suit and pram, was there as a spectator, but only in the marquee, because the noise of former Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason’s V16 engine BRM was too much for the sleeping infant. Mrs Mason’s Ferrari GTO wasn’t exactly quiet either.

Indeed, the world of rock’n’roll was very well represented, with Howard Jones, Genesis manager Tony Smith and Pink Floydster Steve O’Rourke all wearing Nomex racing suits.

There were some big boys from the high pressure world of motor racing, too. Ron Dennis – the boss of McLaren – had swapped clothes and roles with Ayrton Senna, and was driving a 1970 Formula 1 car up the hill, quite slowly, it must be said. John Surtees fell off his 1,000 cc Vincent motorcycle and Damon Hill went all nostalgic by entering the very Jaguar his father had once raced.

As a grand finale, and to keep the children quiet, every single one of today’s claimants for the title of Fastest Production Car In The World had a bash on the course. Some took it very seriously indeed. The $1m BMW-powered McLaren F1 went up the hill so fast that the back of the car had barely set off before the front finished. Inevitably, it was the fastest car anyone saw all day.

Some, such as the new Aston Martin Vantage, were quite fast and others were not very fast at all. The Jaguar XJ220 had a practice, then retired to the pits and was never seen again. Jaguars have been called big cats before. This one was a scaredy cat.

However, its sudden withdrawal was the only piece of politicking, nitpicking or whingeing that anyone saw all day. Except when I had a go.

Behind the wheel of a Honda NSX, I was so slow that I still haven’t finished yet. In fact, I’m writing this while doing it and I have to go now because there’s a corner coming up.

More from 30 Years of Clarkson