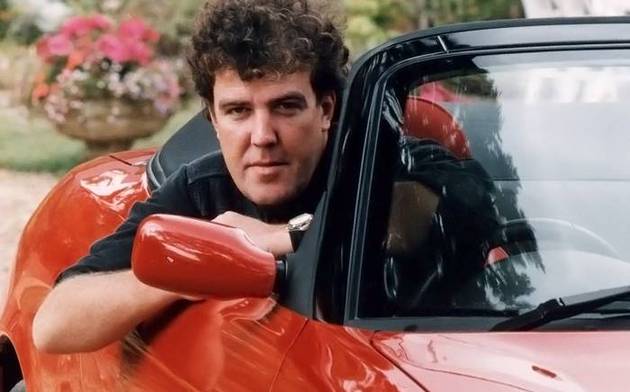

When Jeremy Clarkson handed back his Ford GT supercar (2005)

Sorry, Ford, I have to ask for my money back

This article was first published in The Sunday Times on July 3, 2005

Thirty-five years ago I promised myself that one day I’d own a Ford GT40, the blue-collar supercar that took an angle grinder to Ferrari’s aristocratic halo at Le Mans. But 25 years ago my dreams were dashed as I grew too tall to fit inside.

Happily, in 2002 Ford announced that it was to build a modern-day version of the old racer. It would, the company said, cost less than £100,000 and do more than 200mph. Ford also said it would be much bigger than the original, so pylon people like me would be able to drive it.

And so, two years ago, having tested a prototype in America, I placed an order for one of the 28 that were coming to Britain.

As the months groaned by, there were rumours of big price increases, insatiable thirst and catastrophic suspension failure. But there were also rumours of the supercharged V8 pumping out 550bhp and a mountain of torque so massive it was breaking the testing equipment. So I didn’t mind.

I didn’t even mind when it arrived at my house one month ago inside a truck that had “On Time” written down the side. As we know from the Americans’ arrival at the Second World War, their concept of “on time” differs slightly from ours.

And anyway, it looked so gorgeous, a mass of bulging muscle struggling to contain that massive 5.4-litre, supercharged heart. It doesn’t look like a GT40 but it looks how a GT40 looks in your head. And it’s huge. Longer than a Volvo XC90 and as wide as a Hummer.

Which is why, on its first run, to London, it was like a blue and white Pied Piper, trailing a stream of ratty hatches in its wake. Everyone was taking pictures, waving, giving me the thumbs-up. Never, not once in my 15 years of road-testing cars, had anything drawn such a massive crowd. And never had the crowd been so overtly supportive.

Of course, you can’t run a car such as this without a few problems rearing their heads from time to time. It’s too wide for the width restrictions on Hammersmith Bridge — backing up earned me a slot on the traffic news that morning. The turning circle means every mini roundabout becomes a three-point turn, and at oblique junctions, as is the case in a Ferrari Enzo, you absolutely cannot see if anything’s coming.

But set against this is a surprisingly quiet and civilised ride. It’s like a power station. Silent, as it gets on with the job of brightening up your life.

2005: the year in cars

- Police launch a nationwide network of 3,000 cameras that can read numberplates and alert officers if vehicles are wanted, uninsured or without road tax.

- Europe’s first Chinese car, the Landwind from Jiangling, gets no stars in a safety test.

Mind you, you are constantly aware of the Herculean power that nestles just over your right shoulder. Partly because you can see the supercharger belt whirring away in the rear-view mirror and partly because it makes a deep, dog-baiting rumble when you do put your foot down. Ford asked that I keep the revs below 4000rpm for the first thousand miles. But since 100mph equates to 1900rpm it’s not really a hardship. And at this speed you’re doing 15mpg, which isn’t bad at all. But three days later everything started to go very, very wrong.

As I left the Top Gear studio, the immobiliser refused to un-immobilise itself. So the car was pushed into the hangar and I went home instead in a rented Toyota Corolla.

Ford sent a tow truck, changed the immobiliser and delivered the car to my house the following day. “Is it fixed?” I asked. “Yes,” they said.

It wasn’t. At three in the morning the alarm blew. And then again at four. This meant my wife started to refer to it as “that f****** car”, which took away a bit of the sheen, if I’m honest.

The next day, on the way back to the garage, I received a call on the hands-free phone from the tracker company. “Your car’s been stolen, sir,” said the man. “I’m sure it hasn’t,” I said, “because I’m in it.”

Fearing that I might be the burglar, the man asked if I could give him my password. Tricky one, that, since I have a different password for everything on the internet and can never remember any of them. And that’s a big problem, because the man at the end of the phone has the power to remotely shut down the engine.

I threatened him, lightly, with some physical harm, but this didn’t work so I had to guess. “Aardvark,” I ventured. “Abacus, Aesop, additional …”

Eventually he took pity and I was able to deliver the car back to Ford with some stern warnings about the alarm, the immobiliser and the tracker system, all of which seemed to be malfunctioning. As a courtesy car they gave me a Ford Focus, with a diesel engine. Nice.

Two days later the GT was back. “Is it fixed?” I asked, again. “Yes,” they said.

Five minutes out of the Ford garage I received a text to say my car had been stolen. And then, in the next half-hour, three more. So, counting the two alerts I’d received before I was even out of bed, that meant my car had been stolen five times before 9am.

This time I rang Ford and explained that I would personally come over there and insert the whole car up the chairman’s backside if it wasn’t fixed. And while I was on the phone a yellow warning light came on on the dash.

“There’s a yellow warning light on the dash,” I bellowed, like Michael Winner, only angrier. “Oh, that’ll be something to do with the engine management system,” said the man with the bleeding ears. “You’ll need to get it looked at …”

When Ford gave me the car back after its third hospital trip in as many weeks, I didn’t ask if the security system was fixed. Because the notion of it still being broken was simply inconceivable.

So imagine my surprise when, one hour later, while at my daughter’s school play, I heard a familiar siren. I couldn’t believe it. The alarm had gone off again.

In a fury this time, I called Ford and explained, loudly, that Roush, the company charged with servicing and maintaining the 28 GTs in Britain, was plainly incompetent. And that there was simply no point asking it to fix the alarm again because it’d had three goes already.

I then did something the man at Ford wasn’t expecting. I asked for my money back.

And that, the next day, is what happened.

They put £126,000 in my account and sent a man to pick up the car. “Is it the alarm system?” he said. “They all do that.”

So there we are. A 35-year dream. A two-year wait. Ten years of damn hard work. And what do I get? The most miserable month’s motoring it is possible to imagine.

Strangely, though, as the GT rumbled down my drive for the last time, I felt like Julie Walters watching Michael Caine getting on the plane at the end of Educating Rita. I actually cried.

There’s a very good reason for this. I genuinely believe that some machines have a soul, and I can’t bear to think of my Ford sitting in a warehouse now, unloved and unwanted. It is fine. It is perfect. It knows it’s a great, great car that was ruined by a useless ape who fitted a crummy aftermarket alarm system.

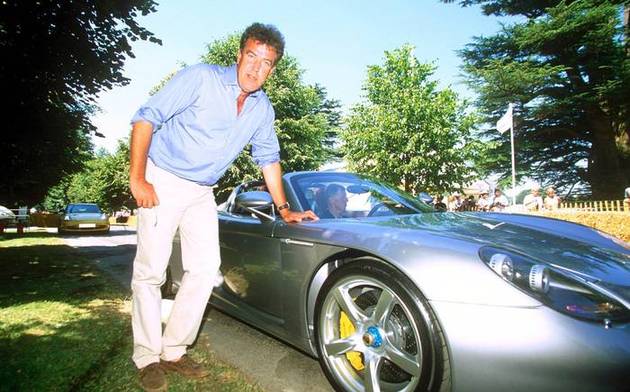

Ford has said I can buy the car back any time. It has even lent me an Aston Martin DB9 while I make up my mind. I don’t know, though. I just don’t know.

Normally I finish these columns with an opinion of mine. But this time it’s the other way round. I’d love to hear yours.

One thing: I know I could sell the car privately and make a £50,000 profit.

But I have never exploited my position as a motoring journalist for profit. And I never will.

More from 30 Years of Clarkson