Air Race E: We meet the man bringing electric motor sport to the skies

Jeff Zaltman wants to replicate the Formula E electric racing series — but in the air

ELECTRIFICATION of the car is well underway as we accelerate towards a point in the not-too-distant future where fossil-fuel-powered road vehicles will no longer be sold. But the same cannot be said of the aviation industry. Electrification of the skies is, essentially, playing catch-up with that of the land. However, inspired by the high-tech electric Formula E and Extreme E motor sport series, it would appear that electric air racing could help accelerate a future of emission-free air travel.

Air Race E is the brainchild of Jeff Zaltman, an American businessman with a proven track record in bringing the excitement of air racing to the masses. He’s the CEO of Air Race 1 World Cup and Air Race Events, representing the pinnacle of wing-to-wing air racing around the globe. Now he wants to use that experience to pioneer electric air racing, which, just like electric car racing, will feed into the development of mass-electrification of aeroplanes.

“Our vision for the series is that we’re trying to take aviation into the future, trying to advance the whole aerospace industry. We’re doing that by enabling it to use electrification and taking it forward on the platform of motor sport,” says the tanned 50-year-old from his home office in Barcelona.

“Motor sport is regularly used as a platform for development of technology, innovation and, of course, taking products to market, ultimately. We expect to be the motor sport platform for the aviation industry.”

Competitors in Air Race 1 fly oval courses at more than 200mph over eight laps

Indeed, while existing air racing, especially Air Race 1, is undoubtedly a thrilling spectacle, it hasn’t influenced wider aerospace industry technology for quite some time. Zaltman readily admits that, but points to the heyday of air racing for inspiration.

“By the 1920s, air racing was actually one of the most popular sports in the world, attracting the biggest audiences. Of course, it was for the amusement of fans, most of which hadn’t even seen an aeroplane, but a lot of technology came out of the early days of air racing.

“It was quite a lot of technology, especially on the aerodynamics and also, how to make aircraft more lightweight, etcetera. The Supermarine Spitfire was one example, which came about due to experience in the Schneider Trophy race, so there’s a real proven legacy there of air racing bringing technologies that can be put to use.”

Air Race E: How it works

The top rung of the international air racing scene runs to an established format, with eight aircraft flying laps of a circuit together at speeds of up to 250mph and sometimes no more than ten metres from the ground. It’s exhilarating to watch. Zaltman’s firm has so far organised races in the States, Spain, Tunisia, Thailand and China – and there’s much more to come. However, now that the format has been developed, he sees an opportunity to repeat the success of the likes of Formula E. In fact, he even spent some time working with the Virgin Racing Formula E team in 2016.

“We have an opportunity to change because we already have this platform. So why not use this motor sport environment, as it’s perfect for testing and proving new concepts. It’s a playground for the future.”

According to Zaltman, he can put together air racing events “in his sleep”, so the major missing piece in the puzzle to bring Air Race E to reality is electric racing planes.

There are two different classes under development. The regulations for the open class were requested by 17 different teams around the world, setting out the rules for the construction of the aircraft, with a maximum electrical power output of up to 150kW – or 201bhp.

There’s massive freedom in the rules for the powertrain, however, encouraging innovation in terms of the battery, electric motor and cooling systems.

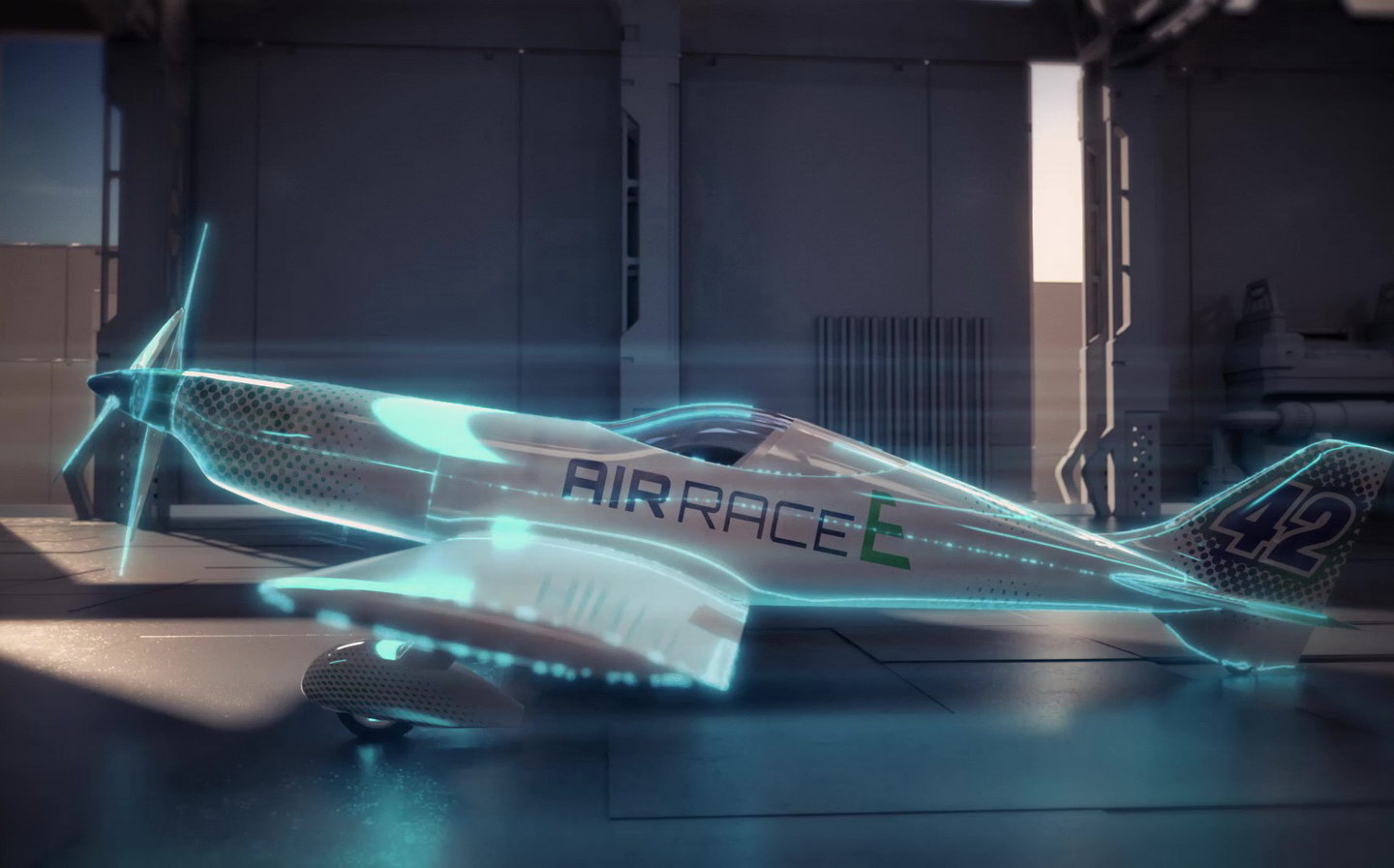

Meanwhile, Zaltman’s company is developing its own aircraft for the ‘performance class’, with up to 100kW (134bhp). It plans to have eight of these ready to race and, presumably, buy.

He’s quick to point out that, while the performance-class planes will all be manufactured equally, aiming for simplicity and safety, he does not expect them to remain the same, as teams will be allowed some freedom to operate them in terms of the aerodynamics, cooling and even recharging the battery.

Challenges of electric aircraft

Unsurprisingly, one of the biggest hurdles for the project is the weight of the electrical components. Zaltman estimates the increase to be between 50 and 100kg, which doesn’t sound crippling until you realise that the Air Race 1 planes weigh just 250kg.

“If you put a big battery in a car, it’s going to go; it might go slow, but it will go and it’s just a question of optimisation. Put a big battery in a plane and it won’t get off the ground – it simply won’t fly. And it could certainly be very unbalanced and even dangerous. It’s all much more weight sensitive.

“And that’s what’s held the industry back, the laws of physics. Aerospace is way behind automotive, certainly in adoption of electric technology.”

Electric planes are a challenge in terms of design, technology and safety

Other than weight, the biggest challenges facing electric air racing are governmental approval of the aircraft, and safety. There have been several high-profile electric car battery fires that burn much longer and are much more difficult to put out, and that issue is potentially even more catastrophic in an airplane.

“When you’re in an aircraft, it’s not like a car, where you obviously can park, step out and run away. You’ve got to control the aircraft all the way to landing. So we have to go through a lot of extra rigorous testing and making sure that any fire can be contained within the battery.

“Then we also need to think about gliding stability when it’s not under power. Like, can the plane actually glide to a safe landing without any power?”

One of the criticisms of electric car racing has been the lack of exciting noise, but Zaltman reckons that shouldn’t be a major challenge for Air Race E. Most of the noise comes from the air going through the propellor, he claims, not the combustion engine that turns it.

That speed will be reduced for the electric racing planes due to the different characteristics of an electric motor — down from about 4,200rpm to 2,700rpm — so the racing should be a little quieter. Of course, the wider aerospace industry will see quieter operation as a major plus point.

On the flipside, the high torque output of the electric motors from low revs should make the race starts even more exciting to watch. The pilots normally hold the plane on the brakes on the starting grid with the throttle fully open and then release the brakes when the green flag is waved, but there may be changes to the design of the propellors required to accommodate the electric motor’s performance.

Will electric aircraft really take off?

While there’s no date set for the first electric air race, that time is getting closer, Zaltman says, and the engineers have made the technology work. For races that are only five minutes long, anyway.

In terms of this technology’s possibility for wider aerospace use, there’s an enormous gap between a five-minute race in a lightweight racing plane and transporting a few hundred holidaymakers hundreds or thousands of miles, but Zaltman is quite pragmatic about Air Race E’s influence.

“For an aircraft to have a purpose in commercial airfare, you’ve got to be able to carry 100, 200 passengers a meaningful distance, from London to Berlin, etc. But you don’t just start by building something like that. That’s not the first step. It has to start on this very small scale.

“But you know, we are actually the cutting edge of the progression of this technology, and we are directly on that evolutionary path to those large aircraft.”

Air racing is a popular sport with online audiences of 1.2m viewers

He’s not the only one that believes that, as Airbus signed up to be part of the project at an early stage – one among many industry supporters. It takes a hands-off approach, encouraging innovation to thrive and allowing access to its vast experience when required.

There’s a link to the project closer to home, too. The University of Nottingham was given a current racing plane to convert to electric power and research the various sub-systems in the process. Word is that its effort is close to being ready for testing.

Zaltman wouldn’t be drawn on when the first electric air racing event will take place, as that will depend on enough teams and planes being ready to compete. He did hint at an imminent historic first test of a racing plane, though.

Once the aircraft is proven, it must be passed by the relevant authorities for flying and then racing. Dozens of cities around the world have already expressed an interest in hosting a round of the inaugural Air Race E, Zaltman says.

In parallel with the efforts to bring electric air racing to the masses, the aerospace industry will be closely looking at the lessons learned during its development.

Development continues ahead of the first race

A lot can happen in a short space of time. After all, it has only been just over a decade since Nissan released the first-generation Leaf electric car, and Tesla – now the world’s most valuable car company – was fighting for its financial life.

If you look at where the electric car industry is now, with the likes of the Lotus Evija, Porsche Taycan and new Mercedes EQE all leading the way, we can only wonder where light aircraft will be in 10 years, and perhaps larger passenger planes not too much after that.

Tweet to @Shane_O_D Follow @Shane_O_D

- If you enjoyed the interview with Jeff Zaltman, the founder of Air Race E, you may enjoy this interview with Alejandro Agag, creator of the Extreme E off-road racing series

- A future in the skies? Hyundai Motor’s boss says flying cars will arrive by 2030

- Goodwood says it will ‘carefully consider’ future flying car demonstrations after Airspeeder crash