Are motorways really the safest roads in the UK?

They can seem daunting, but should they?

Many drivers worry about heading out onto the motorway. It’s no surprise, perhaps, as the speeds are high, the fastest cars can be travelling at quite a rate higher than the slowest, and there are multiple lanes to navigate and intimidating HGVs to be aware of. And let’s not forget that practical training on motorways isn’t a requirement of gaining a driver’s licence (if it were, perhaps more drivers would keep left, but that’s another story).

But is a fear of driving on motorways well founded? Many claim that motorways are in fact the safest roads; is that true, and if so, why? Here we look at the evidence.

Fatalities on motorways, rural and urban roads

Official statistics should put your mind at ease about motorway driving. According to the road safety charity Brake, 10 times as many people die on rural roads in the UK than on motorways.

Rural roads account for over half of all fatal crashes on UK roads, the charity points out, with cyclists, drivers and motorcyclists three times more likely to be killed on a rural versus an urban road (around towns).

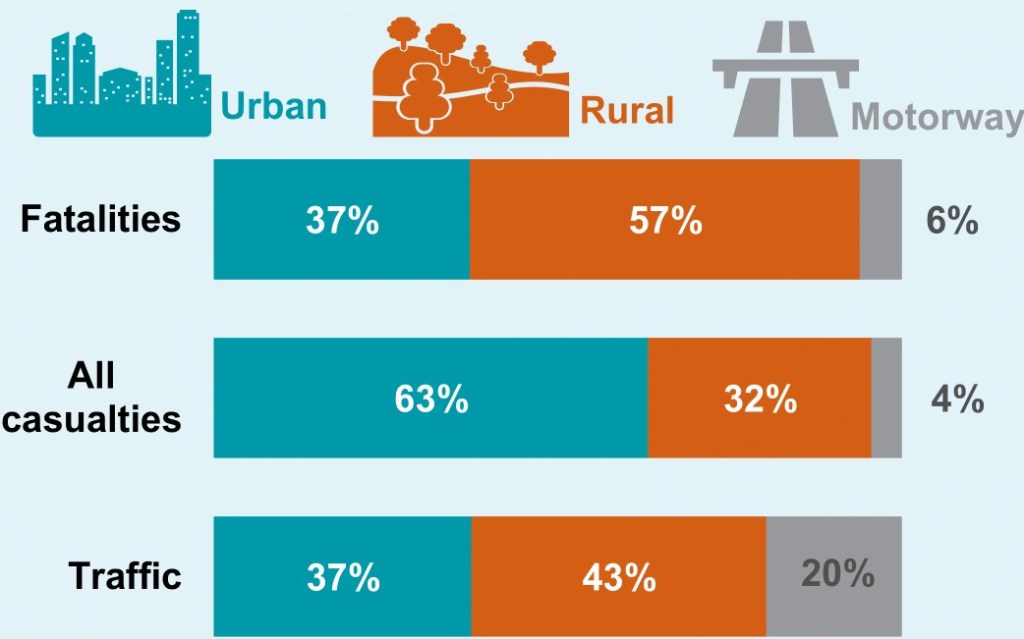

Some 57% of road deaths in Britain in 2020 occurred on rural roads, even though they accounted for 43% of traffic.

Motorways represent the safest roads in Britain, something underscored by the fact that in 2020, according to Department for Transport (DfT) figures, there were 76 deaths recorded on Britain’s motorway network, despite carrying a much higher volume of traffic any other type of road.

They’re safer because oncoming traffic is separated via the central reservation Armco barrier. That makes head-on collisions, with a combined speed of possibly double your own, highly unlikely. Collisions are much more likely to occur with traffic travelling in the same direction of you, which means less energy is involved in a collision.

Motorways also offer hard shoulders or refuge areas (on smart motorways — see below), which means broken down vehicles can often be brought to a halt away from the live lanes of traffic.

And motorways are not open to slow and vulnerable traffic, such as pedestrians, horse riders and cyclists.

Why are rural roads so dangerous?

Studies have repeatedly shown that the most dangerous roads in the UK per head of the population are in rural areas.

Speed is a major factor in making countryside roads unsafe, with a study of “minor” roads estimating that a 10% increase in average speed results in a 30% increase in fatal and serious crashes. For a variety of reasons, the national speed limit (60mph for cars) is rarely a safe speed at which to travel.

Rural roads are often narrow, with blind bends and brows and limited safe places to pass. They may not have pavements or cycle paths, despite being frequently used by some of the most vulnerable road users such as people walking or riding horses. Traffic often includes vehicles travelling at a wide range of speeds from the fast to the very slow.

Last year, for example, 66 horses died and 129 were injured on rural roads according to the British Horse Society.

Rural roads can often have poor road surface conditions and limited or no crash protection or barriers, and, with a higher frequency of debris such as mud and leaves on road surfaces, in wet and icy conditions stopping distances are much greater.

These factors mean that if a driver is going too fast, they may not be able to react in time to a hazard to prevent a crash. They also mean that if a driver is going too fast, they may lose control and end up in the path of an oncoming vehicle or running off the road — both potentially extremely dangerous scenarios often occurring at higher average speeds, meaning that driver fatalities are more likely.

What about urban roads?

With a comparably higher number of pedestrians, higher general populations and denser street networks, urban roads rather than rural roads usually record a higher number of KSIs — a statistical metric standing for “killed and seriously injured”. As the name suggests, this refers to combined deaths and serious injuries on the road.

In 2020, for example, urban roads recorded a KSI rate of 553 per billion vehicle miles versus 224 for rural roads and 49 for motorways. Those KSIs, however, are predominantly accounted for by serious injuries rather than deaths, with accidents generally occurring at lower speeds.

In terms of fatalities, rural roads were still the most dangerous with 795 people killed compared to 520 on rural roads and 76 on motorways.

Are smart motorways safe?

Earlier this year, the government paused the roll-out of “smart” all-lane running (ALR) motorways amid concerns by safety campaigners and MPs following an horrific series of accidents.

At present, data on whether smart motorways are statistically safer than regular motorways is at best conflicting, and the pause on new motorway construction was initiated with the aim of acquiring more data to better guide the future development of smart motorways.

All-lane running motorways were developed to reduce the cost of widening roads and to increase traffic flow by eliminating the hard shoulder. The roads were subsequently rolled out throughout the UK, and more are currently planned despite 39 fatalities in recent years.

As the system expanded, the number of deaths per mile rose from one every 43 miles in 2016 to one every 17 miles in 2019, the latest year for which accurate results are available. This is proportionally a higher figure than for the rest of the motorway network.

According to information obtained by the BBC’s Panorama team in 2020, since ALR sections were introduced on the M25 motorway around London, National Highways recorded a rise in near misses of approximately 2,000%. In the five years before the road was converted into an ALR smart motorway there were 72 near misses; in the five years after, there were 1,485.

National Highways contends that although conventional motorways have lower collision rates than other road types, their casualty and death rates are higher, suggesting that when a collision occurs on a conventional motorway it is more likely that those involved will be killed or seriously injured than in a collision on a smart motorway.

Most dangerous roads in the UK by location

A recent study by the price comparison site Forbes Advisor showed that the UK’s most dangerous roads were in rural Wales.

Comparing the total number of road casualties in each local authority last year with each area’s population revealed the rate of deaths or serious injuries related to population density. The worst area according to the study was Powys, Wales, with 101 deaths or serious injuries per 100,000 people.

Ceredigion, also in Wales, recorded 69 deaths or serious injuries in 2021 (94.5 per 100,000), far fewer than Powys. However, with its relatively sparse rural population, that figure – according to the Forbes research – makes it the second most dangerous place in Britain.

Another study by the Department for Transport examining accident statistics from between 2013 and 2020 found that the most dangerous roads in the UK were in Argyll and Bute in Scotland — again, a predominantly rural area — with an average of 170 accidents every year or 1.99 per 1,000 of the local population.

The road safety charity, IAM Roadsmart, said that the reason behind Bute and Argyll’s status was possibly down to the high number of motorcyclists visiting the area as well as its narrow, twisting roads and dangerous junctions, other factors that underline the dangers inherent in rural roads.

Related articles

- After reading about safety on the UK’s motorways, you may want to read how the public wants 60mph motorway speed limits – according to a WWF survey

- And check out how motorists are being fined millions of pounds for inadvertently entering low-traffic neighbourhoods

- 2030 petrol and diesel car ban: 12 things you need to know

Latest articles

- Skoda Enyaq 2025 review: Same book, different cover for electric SUV

- Lewis Hamilton wants to design a modern day Ferrari F40 with manual gearbox

- Dacia Bigster 2025 review: The ‘anti-premium’ family SUV that punches above its weight

- Your car’s worn tyres could be being burnt illegally in India, investigation reveals

- Open-top 214mph Aston Martin Vanquish Volante is world’s fastest blow-dry

- F1 2025 calendar and race reports: The new Formula One season as it happens

- Alfa Romeo Junior Ibrida 2025 review: Hybrid power adds an extra string to crossover’s bow

- Top 10 longest-range electric cars: all with over 400 miles per charge (officially)

- Renault 5 Turbo 3E ‘mini supercar’ confirmed with rear in-wheel motors producing 533bhp … and insane levels of torque