What are electric vehicle batteries made of, where do the materials come from and are they produced ethically?

The truth about cobalt

Last year global sales of electric cars topped 10 million for the first time, according to the World Economic Forum, representing one in seven of all cars sold. It was a 60 per cent increase on the year before, and most experts agree the figure will continue to accelerate as governments clamp down on vehicle emissions. In the UK, sales of new petrol and diesel cars will be banned from 2020, with hybrids to follow five years later.

Leading the new electric vehicle wave is China, where one in four cars sold in 2022 was an EV. China is also producing huge volumes of electric vehicles and their components, both for the domestic market and export, and for established global brands as well as nascent homegrown start-ups. Experts believe as many as 25 Chinese car brands could be on sale in the UK by the end of 2024.

The next biggest market for electric vehicles was the European Union, with one in five vehicles sold being an EV, while electric vehicle sales in the United States represented one in ten.

With most of the world intent on making the switch from motoring powered by internal combustion engines to electric motors and large battery packs, it’s more important than ever that we know what electric car batteries are made of, and the costs of mining and manufacturing those materials.

- 2030 petrol and diesel car ban: 12 things you need to know

- United Kingdom set for an influx of Chinese electric car brands

The precise individual chemical make-up of each electric car’s battery is a closely guarded secret, but most electric vehicle batteries produced today are lithium-ion and lithium polymer-based, with the major components being steel, aluminium, lithium, manganese, cobalt, nickel and graphite.

The breakdown, according to environmental think-tank Transport & Environment, follows, with information about from where each material is sourced.

Bear in mind that many car makers are now at pains to say they are deeply focused on sustainability, so they may choose not to source materials from leading suppliers and countries if they are known for disreputable mining and production practices. If one car maker is able to sell their products for a lower price than others, it may be as a result of less ethical supply chains.

Graphite: 28.1 per cent

Graphite — the same material that makes up the core of a pencil — is used in EV batteries as the anode. That’s the part of the battery that holds the charged ions of lithium when the battery is charged-up.

Graphite is a relatively affordable and stable material, so there are few safety concerns around it, but it is heavy, and in a typical battery with a capacity of 60kWh it can make up around 53kg of the total battery weight.

- Where is it produced? Some 70 per cent of the world’s graphite reserves are to be found in Turkey, China and Brazil.

- Environmental impact: Mining graphite isn’t an especially intensive process, but it does cause dust pollution and obviously the mining machinery has CO2 emissions of its own. Purifying the graphite for use can mean using unpleasant chemicals such as sodium hydroxide and hydrofluoric acid.

- Political impact: Both the EU and the United States have declared graphite a “supply-critical mineral”.

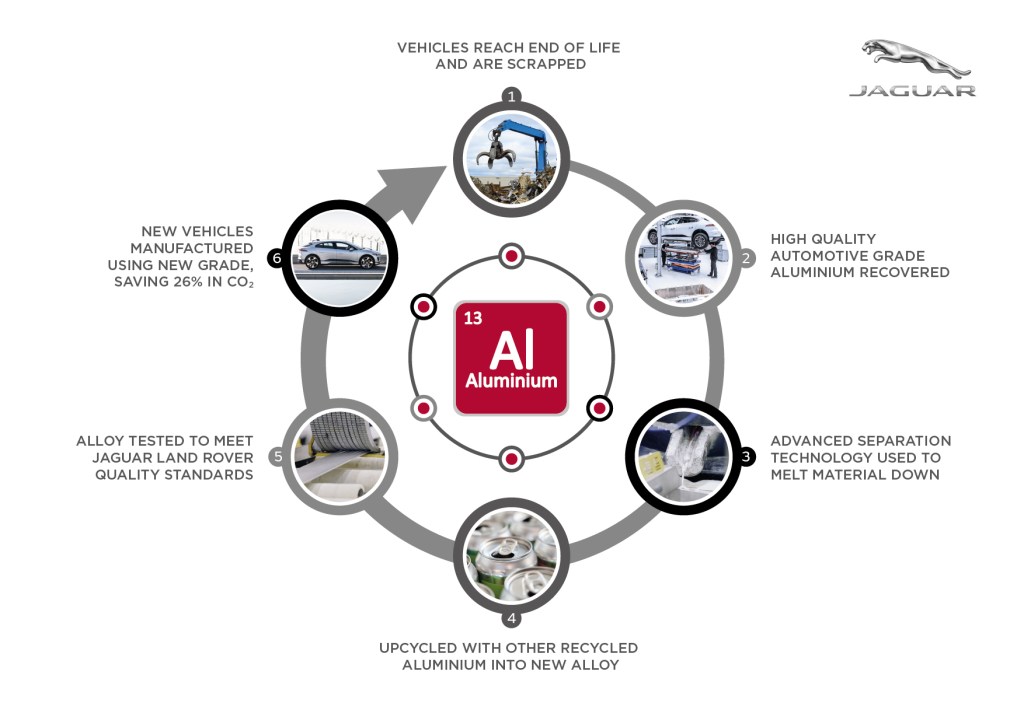

Aluminium: 18.9 per cent

Aluminium is used in the cathode — the negative battery terminal to which the charged ions flow, generating an electrical current. It’s also commonly used for the battery’s casing (as pictured above at the BMW plant in Dingolfing, Germany), and has the benefit of low weight for high strength.

Aluminium is also used for the current collectors, which take the charge generated by the battery’s internal chemistry and connects it to the external electrical circuits, passing it to the car’s electronics and electric motor.

- Where is it produced? Aluminium comes from bauxite mining, with Australia, China and Guinea the world’s biggest locations (in that order), though it is also mined around the world in countries such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Russia and Jamaica.

- Environmental impact: Bauxite is most commonly dug out in open-cast mines. These don’t go very deep, so are less energy intensive, but they are huge in area, requiring vast amounts of land to be cleared and dug, which can lead to habitat loss. Refining and smelting aluminium out of bauxite is energy-intensive, but on the upside, aluminium can be constantly, almost endlessly, recycled. Around 75 per cent of all the aluminium in use has been recycled at one time or another.

- Political impact: There’s no shortage of bauxite nor recyclable aluminium, but bauxite mining in Guinea, the country with the highest proportion of the world’s bauxite reserves, has caused Human Rights Watch to issue warnings over the treatment of residents by multi-national mining companies. With much of the world’s aluminium refining and production coming from China, which is accused of various atrocities from false-imprisonment and torture to genocide, there are also major geo-political concerns about Chinese-sourced aluminium.

Nickel: 15.7 per cent

Nickel is used in the battery’s cathode — the part to which the charged ions flow to generate current — and it’s expensive stuff. A tonne of nickel costs nearly £15,000 at current market prices, and a 60kWh battery might use around 29kg of it.

- Where is it produced? More than 50 per cent of the global nickel resources come from Australia, Indonesia, South Africa, Russia and Canada, according to the Nickel Institute. But it’s also mined in the USA, Colombia, Brazil, Sweden, Finland, Cote d’Ivoire, Tanzania, Botswana, Zimbabwe, China and elsewhere.

- Environmental impact: Nickel’s environmental impact can be significant. Canada, the world’s sixth-largest producer of nickel, has warned of air pollution, water contamination and the destruction of habitats thanks to nickel mining. Environmental journalist Maddie Stone has warned of some of the worst air pollution in the world being caused by nickel mining in Russia, the world’s third largest producer. Some studies have suggested that nickel is the seventh most damaging metal to human health. However, it is easily recyclable.

- Political impact: The largest deposits of nickel in the world are in Indonesia, where accusations have been levelled at mining companies illegally digging up agricultural land belonging to indigenous tribes. Russia is the third largest supplier of nickel, which brings obvious political issues. Indeed, the price of a tonne of nickel spiked above £20,000 in the immediate wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

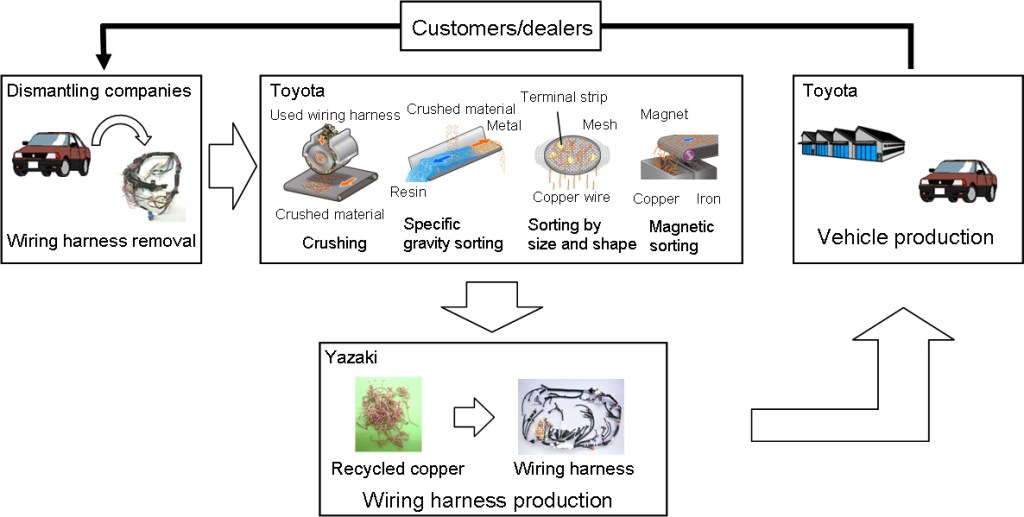

Copper: 10.8 per cent

Copper is abundant around the world and the most commonly used material for electrical wiring, so our cars (electric or otherwise), houses, computers and phones are full of the stuff.

It’s significantly cheaper than most of the other materials used in EV batteries — around £6,500 per tonne. Copper is generally used as a current collector for the battery’s anode, as well as other wiring.

- Where is it produced? Copper is produced all around the world but Chile is by far the world’s top producer, with a 27 per cent share of the market, according to the World Economic Forum. Peru is the next largest producer (10 per cent), then China (8 per cent), the Democratic Republic of Congo (8 per cent) and the USA (6 per cent). Australia, Russia, Zambia and Indonesia each have a 4 per cent share of the market.

- Environmental impact: As with bauxite, copper is usually open-pit mined, and the sheer size of copper mines can cause environmental and habitat issues, and that’s without considering the CO2 impact of the mining operations themselves. There are also air pollution issues, and huge wastage — it takes 99 tonnes of mined material to yield one tonne of copper. Thankfully, copper can be easily recycled (see Toyota’s process above) and doesn’t degrade in quality (assuming no contamination from other materials) with repeated recycling.

- Political impact: Though Chile is generally politically stable, there have been serious discussions in recent years about levying extra taxes on mining companies to fight rampant poverty in the country. Concerns surrounding human rights, trafficking and child labour have also been raised around copper mining in less reputable countries.

Steel: 10.8 per cent

Steel, like copper, is a material so widely used that it’s almost hard to comprehend how important it is to our everyday lives. From the cutlery in our drawers to the structures of our tallest buildings, steel is vital to modern human existence.

In EV batteries, it’s mostly there as protection, in the form of steel structure, to keep the battery’s internal parts safe from impacts and damage.

- Where is it produced? According to figures from the World Steel Association, 140.7 million tonnes of steel were produced in 64 countries during December 2022 alone. That’s actually a 10.8 per cent decrease compared with the year before. China produces by far the most, accounting for nearly 80 million tonnes that month. India is second (10.6 tonnes), then Japan (6.9 tonnes), the USA (6.5 tonnes), Russia (5.5 tonnes) and South Korea (5.2 tonnes). Germany, Turkey, Brazil and Iran are also top 10 producers.

- Environmental impact: Steel, which has to be smelted from iron at high temperatures, is a major contributor to global warming. It’s estimated that 1.83 tonnes of CO2 are emitted for every tonne of steel produced, and around 1.8 billion tonnes of steel are produced worldwide each year. The mining of iron ore, from which steel is produced, is also environmentally damaging. Steel can be recycled, though, and companies such as Volvo, Tata, Vattenfall and SSAB have all been experimenting with carbon-neutral steel production.

- Political impact: Iron ore is the third-most traded commodity in the world, behind only crude oil and coal, so there are profound political issues that can both affect and be affected by the production of steel. The movement of steel production from the industrial heartlands of Europe to the far east caused, and continues to cause, enormous socio-political ructions in the UK.

Manganese: 5.4 per cent

Manganese is used in batteries as part of the cathode, the battery’s negative terminal, and it’s used as a stabilising material, there to help the battery maintain its charging and discharging functions.

It’s a common mineral in the Earth’s crust, and indeed is vital to life — we all need trace amounts of manganese in our diet to be able to grow new cells, bones and even for embryonic development in the womb.

- Where is it produced? South Africa is by far the world’s biggest manganese producer, according to the US Geological Survey’s (USGS) Mineral Commodities Survey 2023. Last year its output was 7.2 million tonnes, way ahead of Gabon’s 4.6m tonnes and Australia’s 3.3m tonnes. China produced a little less than a million tonnes, with Ghana, India, Brazil, Ukraine, Cote d’Ivoire and Malaysia also in the top 10.

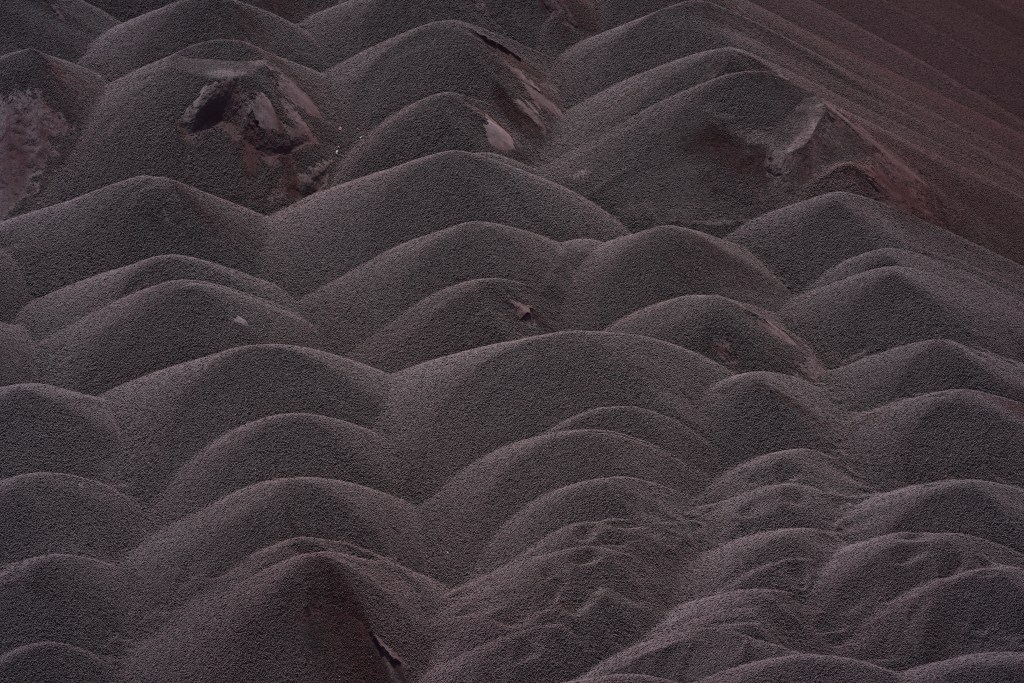

- Environmental impact: Vital for life it may be, but manganese is nasty stuff when there’s too much of it about. Chronic manganese poisoning is recognised as a serious issue when it comes to mining the mineral, and air pollution near manganese mines has been linked to impaired motor skills, cognitive disorders and metabolic processes, especially in children. Water pollution from manganese mining is a major issue. Continued exposure can damage the lungs, liver and kidneys, and cause serious neurological damage. It has been suggested that manganese nodules could be mined from the seabed (see results of that above), reducing its on-land pollution, but environmental groups have warned of sub-sea habitat collapse if major seabed mining plans go ahead.

- Political impact: Because it’s so common, and so cheap — only around £3.20 per tonne — manganese has little serious political impact, but that cheapness compounds the potential for human rights issues in its mining, especially the possible use of child labour.

Cobalt: 4.3 per cent

Cobalt is arguably responsible for more angst over electric car battery production than any other single component. Along with nickel, it’s regularly cited as being extremely vulnerable to the use of child labour in its mining and production, though that’s not always the case.

Cobalt is used in the cathode of the battery, the negative terminal, and like manganese it’s there to stabilise the battery’s chemistry, making it more reliable in the long term.

Manufacturers are now starting to move away from cobalt and towards new battery chemistries, such as China’s BYD Group and its lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery design, which uses no cobalt. This type of battery is fitted to that company’s new Atto 3, Dolphin and Seal electric cars, among others.

- Where is it produced? The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) accounts for around 70 per cent of global cobalt production, according to the USGS. Its output of 130,000 tonnes in 2022 was significant compared with the 8,900 tonnes from second-placed Russia. Australia, Canada, the Philippines, Cuba, Papua New Guinea, Madagascar, Morocco and China made up the remainder of the top 10, in that order by output.

- Environmental impact Cobalt mining can be toxic to the land around mines, with reports of waste dumping “devastating landscapes, polluting water and contaminating crops. High concentrations of cobalt have even been linked to the death of crops and worms, which are vital for soil fertility,” according to environmental group Earth.org. Cobalt is at least ‘endlessly’ recyclable, so as more batteries reach the end of their lives and are recycled, we’ll potentially need to mine less of it.

- Political impact The greatest reserve of cobalt in the world, more than half the total thought to exist, is in the DRC. Amnesty International found that cobalt was mined by children and adults in “horrendous conditions” such as narrow man-made tunnels, where they are at risk of fatal accidents and serious lung disease. What’s more, some of the world’s biggest brands were “failing to ask basic questions about where their cobalt comes from,” it said. Companies such as Volvo and BMW have said that they are instigating ‘blockchain’ digital tagging methods to try and eliminate such sources of cobalt for their batteries (Volvo’s are produced by CATL in China and LG Chem in South Korea), but according to Amnesty there are still too many gaps in the reporting chains.

Lithium: 3.2 per cent

Even though lithium makes up a tiny percentage of a battery’s size and weight, it’s the most important component from a power perspective. It’s the movement from the anode to the cathode of lithium ions that creates an electrical current that can then be used.

There is some potential for lithium to be replaced — other materials such as magnesium and sodium have shown some promise — but for now, it’s the basis for the best type of battery on offer, in terms of energy density and length of life.

- Where is it produced? Australia produces more than 50 per cent of the world’s lithium, according to the World Economic Forum, with an output of 55,400 tonnes in 2021. Chile was second (26,000 tonnes), then China (6,000 tonnes). Other countries include Argentina, Brazil, Zimbabwe, the USA and Portugal.

- Environmental impact: Lithium in itself isn’t especially harmful — indeed, you’ll find traces of it in our food, our teeth and our bones — but mining it requires a lot of water. As much as 500,000 litres of water are needed to get one tonne of lithium out of the ground, and that can lead to localised water shortages as well as potential river and water table pollution from run-off.

- Political impact: Lithium is proving to be politically troublesome, as most of it is found in very few places — more than half of the world’s supply concentrated in South America’s ‘Lithium Triangle’ that covers Argentina, Bolivia and Chile, and there’s a lot in China, too. What’s more, “Only a handful of companies can produce high-quality, high-purity lithium chemical products,” according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), and new lithium mines can take an average of 16.5 years to get ore out of the ground. It’s not surprising that the IEA reckons by 2025 we could be looking at a significant lithium shortage. The gap between demand and supply could be even worse than that. “We currently in the US produce around 20,000 tons of lithium hydroxide refined in the US. We think we need over 700,000 by the second half of this decade. So, 35 times more,” Keith Phillips, CEO of Piedmont Lithium, whose customers include Tesla and LG Chem, told Yahoo Finance.

Iron: 2.7 per cent

Iron is used as part of the construction of the cathode. It’s an abundant element, and in common use everywhere, as well as being a vital component of steel-making. There is also some potential for iron to replace lithium in the batteries altogether — experiments have shown promise, and iron is cheaper by far than lithium.

- Where is it produced? Australia tops the charts for iron or mining, with a usable output of 880 million tonnes in 2022, followed by Brazil (410m tonnes), China (380m tonnes), India (290m tonnes) and Russia (90m tonnes). The rest of the top 10 producers are Ukraine, South Africa, Iran, Kazakhstan and Canada.

- Environmental impact: As mentioned above, iron ore is the third most traded commodity on Earth, so mining operations are huge. While they’re not especially toxic, not in the way that manganese mining can be, there are pollution impacts from the physical mining processes, as well as potential water pollution impacts from heavy metal and acid run-off.

- Political impact: With iron ore being so common, and such a broadly-traded commodity, its general political impacts are low, but there are some underlying issues. For example, most of the trade between China and Australia is in iron ore, and growing political tensions in the South Pacific could trigger supply issues in iron if those two countries have a major falling-out, which could have significant knock-on economic effects.

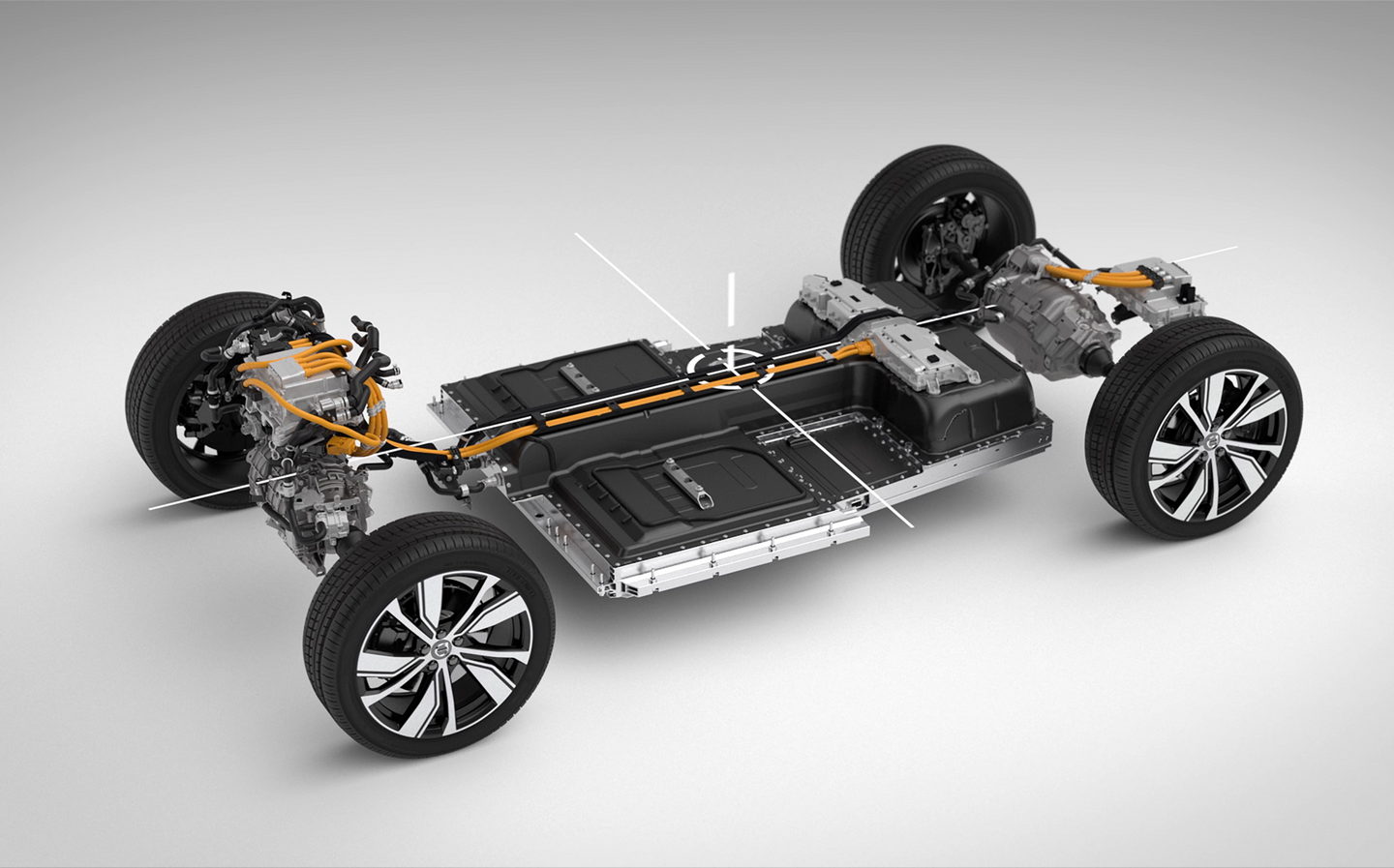

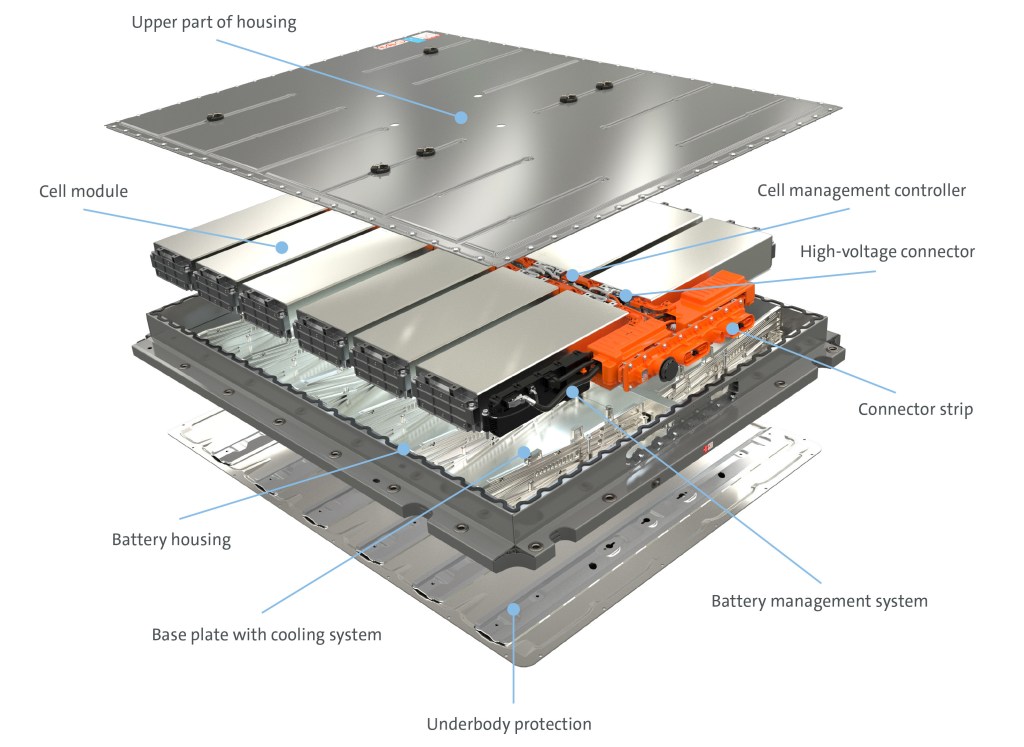

Battery design

There are three primary types of battery design for EVs — cylindrical, prismatic and pouch.

Cylindrical

Cylindrical batteries are made up of individual compact round batteries, which look — and at a basic level, function — like regular household AA and AAA batteries. Link enough of these together and you get a large battery stack, with sufficient power to drive a car.

It sounds a bit old-fashioned, but it’s actually the design that Tesla uses, and it has been proven to be relatively safe, long-lasting and powerful.

Most cylindrical batteries are quite small, at the individual level, and that’s better for cooling and avoiding the dreaded ‘thermal runaway’ — where a battery can’t regulate its heat anymore, leading to a potentially catastrophic fire.

Larger cylinders would, theoretically, make a cylindrical battery more powerful and more efficient, but cooling becomes trickier. Cylindrical batteries aren’t the most space efficient, because the round shape of their cells leaves gaps in the structure.

Commonly used by: Tesla, Lucid, Rivian

Prismatic

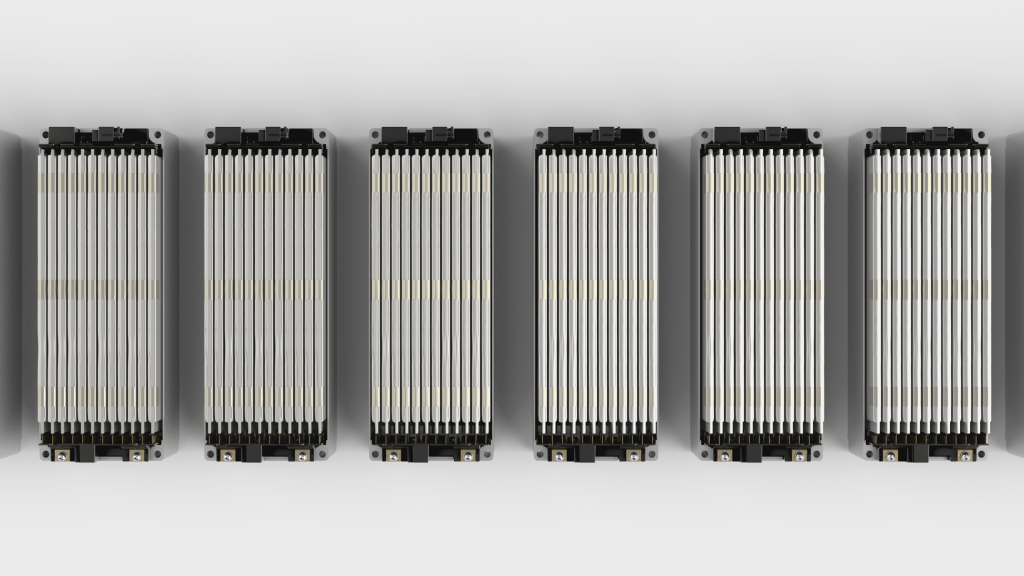

Prismatic batteries are made by either rolling or stacking wafer-thin sheets of anode and cathode materials, and enclosing them in a solid case, usually square or rectangular in shape.

Prismatic batteries are space efficient, because these cases can be stacked hard up against one another, and they have the potential to be much more powerful than a cylindrical battery, because you can stack more material inside each section than you can with a cylinder battery.

Prismatic cells are, potentially, becoming the industry standard as they’re especially suited to the newer lithium iron phosphate battery chemistry design that is gaining ground among China’s hugely influential battery makers, and which can do away with some of the more troublesome battery chemicals, such as cobalt.

They’re also reckoned to be more reliable and less prone to ‘thermal runaway’ than other designs.

Commonly used by: Volkswagen, Ford, BMW, BYD

Pouch cells

Pouch cells package their anode and cathode material into a pouch that is usually made of plastic. They’re about the same size as a slim notebook and — usefully for car designers — they can be packaged into smaller and more complex shapes than prismatic or cylindrical cells.

The major downside is protection — pouch cells need a hefty structure to protect them from damage, as if a cell is broken open it can quickly lead to a fire or electrical short.

Commonly used by: Mercedes, General Motors, Volvo

Related articles

- After reading about the materials needed to make EV batteries, you may also like to check out all the car makers’ electric vehicle plans

- Wondering what are the best EVs right now? Check out our electric car reviews here

- Or read more about the agreement between Aston Martin and Britishvolt, signed earlier this year

Latest articles

- Lewis Hamilton wants to design a modern day Ferrari F40 with manual gearbox

- Dacia Bigster 2025 review: The ‘anti-premium’ family SUV that punches above its weight

- Your car’s worn tyres could be being burnt illegally in India, investigation reveals

- Open-top 214mph Aston Martin Vanquish Volante is world’s fastest blow-dry

- F1 2025 calendar and race reports: The new Formula One season as it happens

- Alfa Romeo Junior Ibrida 2025 review: Hybrid power adds an extra string to crossover’s bow

- Top 10 longest-range electric cars: all with over 400 miles per charge (officially)

- Renault 5 Turbo 3E ‘mini supercar’ confirmed with rear in-wheel motors producing 533bhp … and insane levels of torque

- British firm Longbow reveals ‘featherweight’ electric sports cars with 275-mile range