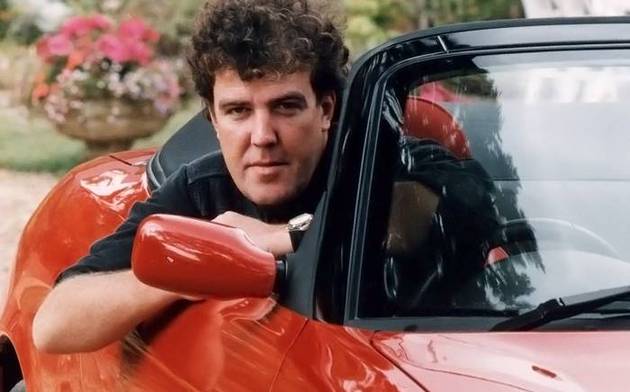

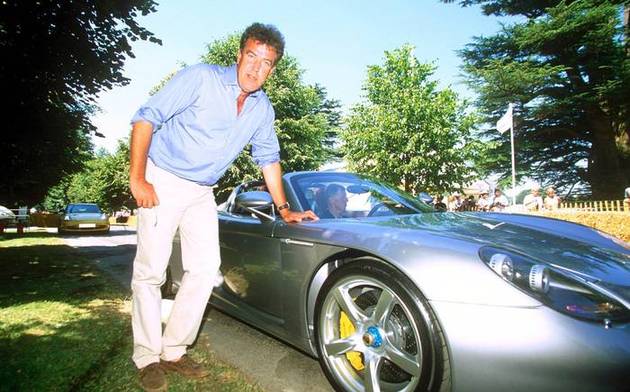

The Clarkson effect: Do Jeremy's reviews affect car sales?

Can one well-aimed Clarkson comment really send sales through the roof or close factories?

In April 2005, MG Rover called in the administrators. Allegedly, it wasn’t the fault of the directors who had taken £40m in pay and pensions. Neither was it down to the limited model range. It wasn’t even because of the poor reputation that British cars had from the days of the Austin Allegro. The culprit was Jeremy Clarkson, if you believed staff at the Longbridge factory.

“Clarkson’s contributed to the situation,” said Jeff Ali, a manager at the plant. “He’s been very derogatory about the cars and people hate the guy. He’s not welcome here.”

A banner across the gates read: “Anti-Clarkson campaign.”

Owners were quick to join the condemnation: “His tasteless, uninformed anti-Rover prattle dissuaded many potential customers from trying out and buying the cars,” read one of the printable website forum posts.

Anyone who had been in Luton four years earlier would have experienced a sense of déjà vu. At the time, Vauxhall had announced that it would stop producing the Vauxhall Vectra there. The workforce blamed Clarkson.

He had savaged the model on Top Gear for being so dull that the only thing he could think to talk about was its coat hooks, and took a similar tack in The Sunday Times, devoting his column to the reed warbler instead of the car.

The coverage reportedly caused a walkout at Vauxhall’s factory and led to the managing director complaining to the BBC. The car was seen as a disappointment because it at first sold fewer models than its older rival, the Ford Mondeo.

“A lot of people you speak to will still talk about that — they remember it,” said Denis Chick, a former Vauxhall PR man. “It didn’t stop people buying Vectras.”

There may not be a definitive link between Clarkson’s comments and Vectra sales but some note that the Vectra name died long before the Mondeo was canned by Ford (due to buyers turning away from saloon cars more generally).

In contrast with the Vectra, the Ford Mondeo was a car Clarkson loved with a passion, as highlighted in this segment for The Grand Tour.

The industry calls it the Clarkson effect, which is said to make or break a car’s fortune. A favourable review will have thousands heading into the showrooms. A negative review will have a similar effect — except that the hordes will be buying rival models.

This pied-piper phenomenon has marketing heads waking up in cold sweats the night before a review is published, and agonising over whether they should lend him a car to test-drive, running the risk of an acerbic and instantly memorable putdown.

Such as in the case of the Porsche Cayenne (“I have seen more attractive gangrenous wounds than this”), the Peugeot 307CC (“It’s like running into an old girlfriend who, since you last saw her, has had three children, cut her hair, eaten all the pies and given up)” and the Perodua Kelisa, which “sounds like a disease”.

“The Jeremy Clarkson effect is renowned within the car industry,” said Jamie Matthews, chief executive of Initials Marketing, an agency that develops campaigns for car brands. “He can make or break car launches.

“He’s entertaining and eccentric, but he’s also the car expert who has an opinion, and that’s what buyers want: they are looking for a strong point of view about a car to guide them.”

So how much is a positive verdict in Britain’s bestselling Sunday broadsheet worth? About 7,000 cars, according to one large manufacturer. That’s the number of extra vehicles it expects to sell if one of its cars gets a rare five-star review in The Sunday Times.

A spokesman for the company, who asked to remain anonymous, said that the Clarkson effect doesn’t stop there. It helps bring more people into showrooms and paints the rest of their range in a good light.

When Top Gear was revived on October 20, 2002, the first episode featured Clarkson testing — and raving about — the Citroën Berlingo Multispace family car. Before the show Citroën had sold 200 cars that month. Eleven days later it had sold 800 and was having to import extra cars to meet demand.

“There was a massive uplift on the back of that,” said Marc Raven, the PR man at Citroën UK at the time. “We couldn’t quite believe it.”

“What he says has a huge impact,” agrees Alun Parry, from Suzuki. “Jeremy gave four stars to the Swift in 2010 and the same to the Swift Sport in 2012. Sales of that car were 105% of the target for the year.

“You can’t say that was all down to Jeremy, but when he likes a car, it certainly gets a lot of people talking about the brand.”

When Clarkson recommends luxury cars it can have an even more significant effect. One upmarket car maker said it witnesses an 800% increase in website visits if a particular model is well reviewed by Clarkson.

The fear for motoring’s marketing people, though, is that he’ll find a car that is worse than the Vectra, which in turn could lead to a consumer boycott, factory closures and thousands on the breadline.

Not so fast…

Or perhaps not. As with everything about the man, the Clarkson effect is prone to exaggeration, and he’s the first to admit it.

“‘I don’t have any influence over what people do, I really don’t. It makes no difference what I say,” said Clarkson at the Hay festival in 2008.

He emphasised the point in a column from July 1999, explaining how the Chrysler Voyager became the second-bestselling people carrier in Britain just after he described it as “the worst car you can buy now”.

Then there was the time he awarded just one star to the previous-generation BMW 1-series. It became one of the five best-selling cars in its class.

That argument doesn’t wash with road safety campaigners. Co-op insurance, the road safety charity Brake and the Green Party are some of the groups who have criticised the presenter. They claim he encourages reckless driving. Richard Brunstrom, once Britain’s most senior traffic officer, blamed him for turning motorists against speed cameras in 2004.

Clarkson’s response, in a Sunday Times in an interview in 2005, was to the point: “When people say [I’m a role model], I ask, ‘Would you do something just because I did it?’ And they always say no. And I say, ‘Well, if you wouldn’t, then why do you think someone else would?’”

Then again…

But Clarkson’s claim that no one takes any notice of what he says may be an exaggeration in itself, as there is apparently strong evidence that he can move markets internationally, close factories and influence the development of new products. Just not necessarily in the world of cars.

In 1998 he was blamed in a clothing industry report for causing a 14% drop in jeans sales. Children and teenagers saw him on screen and decided that “they do not want to look like their dads”, the report by the market research company AC Nielsen stated. Soon afterwards Levi’s laid off 6,000 staff.

Clarkson said that he would stop wearing his favourite trousers — if the clothing firms paid him £40m.

But whether he’s the force behind thousands of car sales a year, or completely ignored by the hundreds of millions of people who watch his shows and read his columns, one fact remains constant: it simply doesn’t matter because he just tells the truth.

“I’m not employed to think one thing and say something else,” he wrote in one column. “Am I supposed to recommend all cars that are made here, irrespective of their price, performance or quality? Because if I am, all of you must go out tomorrow and buy a London cab.

“Let’s just say that I had been nicer to the Vectra, and let’s just imagine for a moment that people pay the slightest bit of attention to what I write,” he wrote in a separate article.

“Then yes, more people might have bought one. But now they’d be the ones writing to me, wondering why I hadn’t warned them of its numerous shortfalls. And calling me a git.”

More from 30 Years of Clarkson