What is synthetic e-fuel and will it make electric cars obsolete?

Future fuel or another fossil?

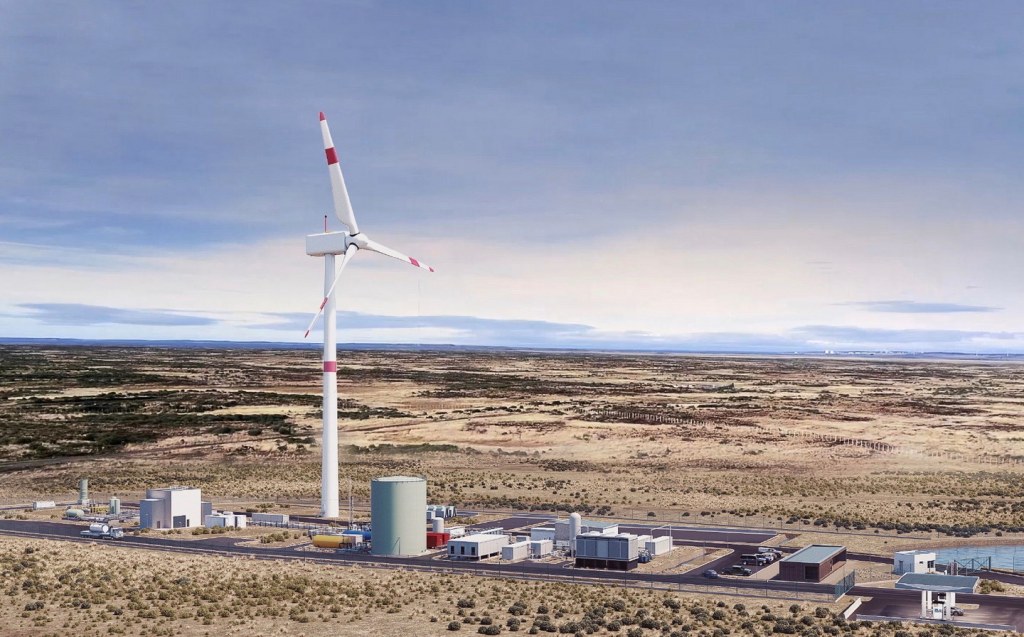

When Porsche announced that it was teaming up with Siemens and the energy firms ENEL and AME to build a synthetic e-fuel factory in Chile, it was music to a lot of people’s ears.

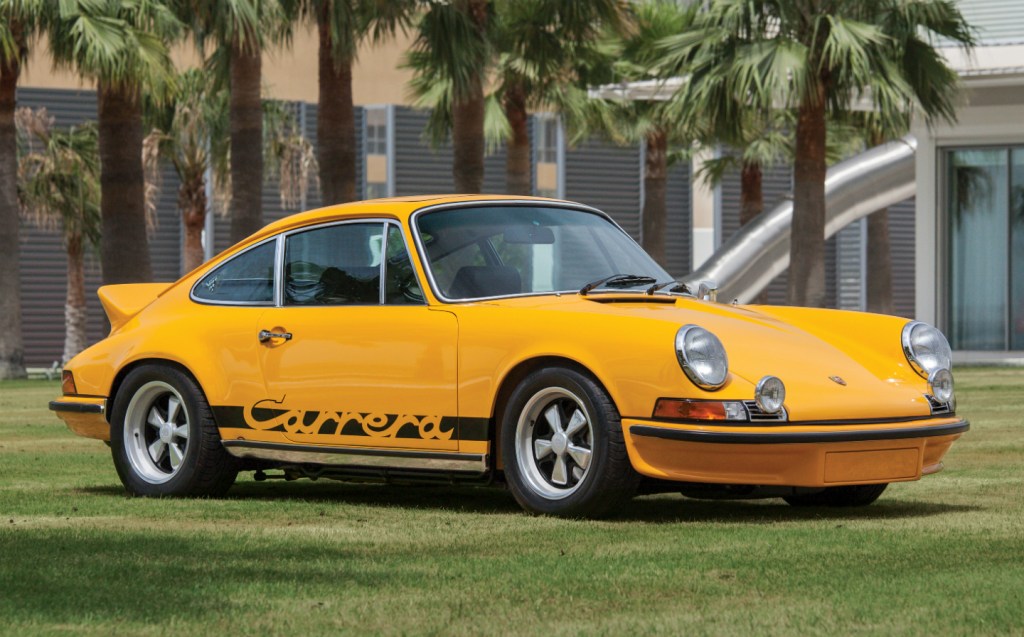

The idea of e-fuels, many thought, wouldn’t just allow owners to keep their classic Porsches on the road, it might entirely save the internal combustion engine from extinction.

After all, why bother with the potential for “range anxiety” and overnight charging when you can just continue fill your car up at any petrol station with near-carbon-free fuel?

What’s more, according to Bosch — another company investing in the field — you’d be able to do so for just £1 per litre?

For manufacturers, too, surely the potential for synthetic fuels would see them abandon wholesale electrification programmes in favour of a much more cost-effective alternative.

So why aren’t synthetic e-fuels being talked about more?

What is an e-fuel?

Synthetic e-fuels are, in theory, almost carbon neutral. Certainly less carbon intensive than regular oil-based fuels.

Porsche’s Chilean project, for instance, would see hydrogen extracted from water via an electrolysis process powered by an on-site wind farm. Carbon is drawn from the atmosphere and, using a methanol synthesis reactor, converted into methanol.

Combining the hydrogen and methanol creates a combustible hydrocarbon that could be used in an internal combustion engine with few, if any, modifications.

What are Porsche’s plans for synthetic e-fuels?

Porsche said that in future the Porsche Supercup racing series would be entirely powered by synthetic e-fuels made at its Chilean plant. With 70% of the cars the company has ever made still on the road, it says e-fuels are one option that will allow them to remain there, highlighting the fuel’s potential use in keeping other classics going well into the future.

Porsche also indicated that it would use the fuel to power the cars in its Porsche Experience Centres, and the consortium behind the project in Chile said that it planned to ramp up production to 55 million litres by 2024, and 500 million litres by 2026.

The company seems to have gone a bit quiet on the prospects recently, according to some reports.

Keeping classic cars and historic motorsport going

In 2023, the Goodwood Revival historic car racing event held its first e-fuel-powered race, the Fordwater Trophy, involving classic Porsche 911s. It was a success, and so in 2024 all competitors were instructed to run on the fuel.

In the words of Jenson Button, the 2009 Formula One world champion who took part in that Fordwater Trophy race, “What’s so exciting about these fuels is that they can guarantee the future of historic racing, enabling us to enjoy combustion engine cars for years to come.”

It will also mean the classic road cars might be future-proofed, should any rules be brought in banning combustion vehicles from UK roads. It should be noted that no such plan has been tabled to date; the much talked-about 2035 ban on combustion vehicles (or 2030 again, according to a Labour party pledge after it won the 2024 general election) applies only to new cars, and owners of used petrol and diesel cars will still be able to drive them under current rules.

However, some politicians in Paris have been looking to introduce bans on all combustion vehicles, or at least punish drivers of the city’s heavier, more polluting vehicles with tripled parking charges.

E-fuels are considered by some as a way to delay or put an end to such talk, and the inevitable problems it would cause for classic car owners.

Are there downsides to synthetic e-fuels?

Synthetic e-fuels have a huge number of upsides and will almost certainly have a future, though there are enough issues to suggest it may not go so far as to “save” the internal combustion engine in the face of battery-electric vehicles.

The chief problem with e-fuels is economics. Some 500 million litres of e-fuel is barely a drop in the ocean compared to the 45-50 billion litres of petrol and diesel consumed every year in the UK alone; the United States uses 467 billion litres every year.

According to an e-fuel advocacy group, the eFuel Alliance, this is not such a problem because it does not forecast a sudden switchover to synthetic fuels, rather the gradual addition of synthetics to the petrol admixture, say 4 per cent by 2025, 12 per cent by 2030 and 100 per cent by 2050. The group also said that eventually synthetic fuels could cost between £1.15 and £1.87 per litre.

The current average cost per litre of petrol is £1.44 per litre, so the e-fuel prediction sounds terrific.

However, another source — the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a US non-profit organisation — says this is totally unrealistic, putting the cost at between £2.50 and £3.35 per litre by 2030. While £3 per litre for petrol may not seem unreasonable for small-scale, hobbyist applications, for those covering a lot of mileage, it will undoubtedly seem excessive.

The fact remains, too, that while synthetic e-fuels can be mostly carbon-neutral to produce, they’re not carbon-neutral at point of use; that’s also before taking the carbon cost of shipping into account. Though road haulage in some territories might be cleaned up over the next decade or two, transport by sea is likely to be far from carbon neutral for some time to come.

Although synthetic e-fuels may be some 85 per cent less carbon intensive than current liquid fuels, that still isn’t zero, which, considering the scale of the climate crisis, some say simply isn’t good enough.

Another question occurs when it comes to the hydrogen required to make synthetic fuels: just how green is it? Porsche’s Chilean project will, admittedly, extract its hydrogen using wind energy, but the majority of hydrogen produced globally at the moment is created using energy from fossil fuels.

To scale up production of green hydrogen created using electrolysis would require vast amounts of energy beyond the current infrastructural capabilities of most countries.

The UK clean-transport advocacy group, Transport and Environment, says that synthetic e-fuels are four times less energy dense than batteries and, according to its analysis, if just 10 per cent of all the UK’s cars and vans used e-fuels, it would require three times as much renewable energy as the same number of battery-powered vehicles.

Ultimately, the mass adoption of synthetic e-fuels may also be stymied by a lack of consumer demand.

With a number of governments around the world, including that of the UK, planning to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030, the demand for old fuels may simply fall away for everything other than heritage applications.

One of the biggest complaints about electric vehicles just now is their relative expense compared to internal combustion cars, largely due to the cost of their battery packs. But manufacturers predict that electric cars will begin to achieve price parity with internal combustion models by 2028, with the purchase price coming down further thereafter.

If this is the case, by the late-2030s or early-2040s, for many holdouts the economics of running an internal-combustion engine as an everyday driver may no longer stack up. Synthetic e-fuels for road use may, by then, be of little interest to anyone other than leisure users such as classic car enthusiasts, historic racing teams and bikers. But for that particular niche, e-fuels could be vital.

Related articles

- If you found our guide to synthetic e-fuels interesting, you might like to read how a man drove an electric Porsche 2,834 miles across America

- And check out what every car maker has planned in terms of new electric cars

- Will F1 survive the electric car age? Documentary explores its fight to stay relevant

Latest articles

- Should I buy a diesel car in 2025?

- F1 2025 calendar and race reports: The new Formula One season as it happens

- Zeekr 7X AWD 2025 review: A fast, spacious and high tech premium SUV — but someone call the chassis chief

- Denza Z9GT 2025 review: Flawed but sleek 1,062bhp shooting brake from BYD’s luxury arm

- Extended test: 2024 Renault Scenic E-Tech review