Will flying cars ever take off?

The ultimate trophy for the upwardly mobile, flying cars are a reality at last. But will they be more than playthings for the rich, asks Nick Rufford

ARE WE close to a new era of commuting to work in personal air and land vehicles (that’s flying cars to you and me)? It is an appealing idea: the freedom of the skies, no traffic jams and maybe no vehicle tax. There has been a flurry of news suggesting it is about to come true.

A Dutch firm, PAL-V, has developed a road-going gyrocopter with foldaway rotors — the kind of machine James Bond would use to evade his pursuers. On land the ’copter will hit 62mph from standstill in less than nine seconds. When you run out of road, it simply transforms into an autogyro, seating two in tandem. With an eye on the American market, the manufacturer has set up a flying school in Utah for a new generation of upwardly mobile drivers who can afford the basic machine’s £324,000 price tag.

Meanwhile, Larry Page, co-founder of Google, has announced the launch of a single-seat machine called the Kitty Hawk Flyer. Battery-powered and designed to take off and land on water, it skims along in the manner of a giant toy drone. Its cost has not been revealed, but Page promises it will be affordable when it is launched later this year.

Search the internet and you will find dozens of hopefuls from crowdfunded start-ups to ideas hatched by aerospace companies

Then there is the Transition, a light plane with wings that tuck away so you can drive it home from the airport at motorway speeds and park it in your garage. Terrafugia, the company that makes it, was recently bought by Geely, a Chinese car manufacturer that already owns Volvo. If nothing else, it suggests there is serious money behind flying cars.

In fact, search the internet and you will find dozens of hopefuls. They range from crowdfunded start-ups based in sheds to ideas hatched in the laboratories of tech giants or aerospace companies. The proliferation of wonderful contraptions is reminiscent of the early years of powered flight. Some of the new machines use wings to provide lift, some rotor blades; some are equipped with mini-jet engines, others with giant fans.

All come with the same promises: to revolutionise personal travel, cut congestion and liberate swathes of unused airspace. The problem is, the idea has been around for decades but, if you’ll pardon the expression, never taken off. As far back as 1940 Henry Ford wrote: “Mark my word. A combination airplane and motorcar is coming. You may smile. But it will come.”

Nine years later he was proved right when Moulton “Molt” Taylor, an American inventor, launched the Aerocar. It had a road speed of 60mph, flew at 110mph and was a wonder of engineering. One flew Raul Castro — Fidel’s brother and now the Cuban president — around Cuba. The same machine was used from 1961 to 1963 as a traffic-watch aircraft for the KISN radio station in Portland, Oregon. For a while it seemed as though the age of the flying car had arrived, and the concept was popularised on television and in film, notably by Buck Rogers, Supercar and The Jetsons.

But it remained an invention in search of a market. Only six Aerocars were built. In reality, the automobile remained the fastest way to get around on the ground, and pure aircraft ruled the skies. The flying car was an awkward and expensive hybrid that became the butt of jokes and shorthand for unrealistic predictions about the future, as in: “Yeah? So where’s my flying car?”

Plenty of drivers struggle to control vehicles in two dimensions, let alone speeding around in three

Recently, though, there have been advances in three key areas. The first is strong, new materials such as carbon fibre and alloys — the key to making lightweight aircraft that are “roadable”, to use an American expression. Second, powerful batteries — a spin-off of electric car development — plus the sort of compact jet engines that deliver more thrust from less fuel. Third, intelligent electronics for flight control and navigation that make self-flying cars or aero taxis a real possibility.

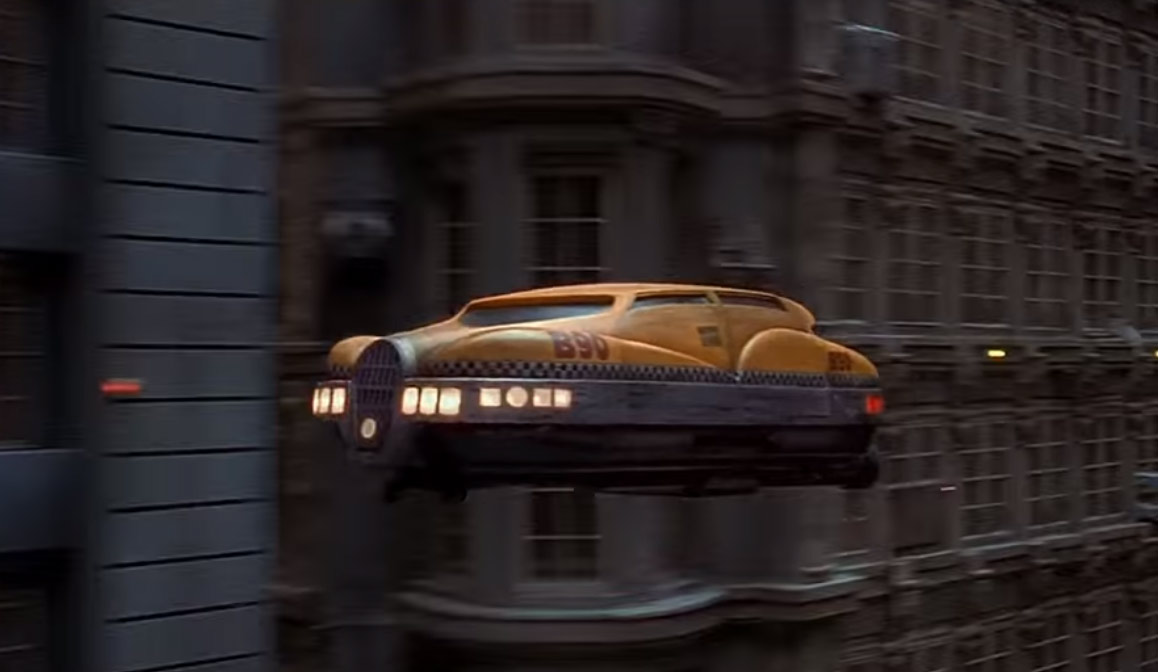

The cars that skimmed over the Los Angeles of 2019 in Blade Runner were referred to as “spinners” — flying cars that used thrusters for vertical take-off and landing (VTOL).

The real-life equivalent made its maiden voyage at an airfield near Munich this year. It’s called the Lilium Jet, though it has no jet engines. Instead it flies using 36 electrically powered propellers. The test flight lasted just a few minutes, with no one in either of the two seats and a pilot controlling it from the ground, but, if it makes it into production as the world’s smallest VTOL craft, it could revolutionise air transport (though it won’t be equipped for driving).

A German competitor called Volocopter has received €25m (£23m) from the vehicle manufacturer Daimler to help develop another two-seater VTOL craft. It looks more like a conventional helicopter — in contrast to the Lilium, which resembles a flying computer mouse — but, like its rival, it is battery-powered.

With this rate of progress, surely it won’t be long before we’re flying to the supermarket. Unfortunately, while the technology may have caught up with science fiction, air traffic regulations have not. Any machine that can lift itself off the ground and stay aloft must fly under Civil Aviation Authority rules in the UK and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) laws in America. That alone is enough to ensure flying cars do not become commonplace soon.

Anyone wanting to fly from home to work, for example, would for a start need a pilot’s licence, which usually takes about 70 hours of flying and months of part-time ground school. If their journey took them through controlled airspace used by commercial or military traffic, they would need air traffic control permission.

Flying cars such as the Dutch gyrocopter would be classed as a single-engine helicopter, which means it would have to stick to air corridors — along the Thames in London, for example. So nipping to the shops or lifting off from a traffic jam would be a non-starter. The Transition is a single-engine plane, which means it has to steer clear of cities in case the engine fails.

You don’t need a pilot’s licence to operate Page’s Kitty Hawk in America because it weighs so little, but its lightness is due to it having floats instead of wheels, so it can’t provide ground transport. In the UK there’s no similar ultra-light category, so only qualified pilots will be able to fly it.

There is little chance of these rules being relaxed. Plenty of drivers struggle to control vehicles in two dimensions, let alone speeding around in three. Indeed, as airspace becomes more congested, the bar is likely to be raised. Air traffic systems in the UK are already almost at full capacity, without hundreds of flying cars doing short, unscheduled hops. One limiting factor is the number of air traffic controllers. Another is the number of flights that a radar-based TCAS (traffic collision avoidance system) can handle at any one time.

Imagine the scale of complaints provoked by machines clattering overhead, with all the implications for noise and prying eyes

Then there’s the cost. For the price of a PAL-V you could buy a Robinson R22 helicopter (which has a longer range) plus a car to take you to and from the helipad. Likewise the Transition. Its projected price in 2011 was almost $280,000 (£218,000 at today’s rates). With production not due until 2021, that’s almost certain to increase.

Finally, there’s the problem of privacy. One technology expert recently said: “I love the idea of being able to go out into my back yard and hop into my flying car [but] I hate the idea of my next-door neighbour having one.” Imagine the scale of complaints provoked by machines clattering overhead, with all the implications for noise and prying eyes.

A more realistic vision of the future appears on film in The Fifth Element, set in a futuristic New York City, with a wisecracking Bruce Willis driving a flying taxi through congested air traffic. Being a passenger in an air taxi flown by a qualified pilot will become a reality much sooner than the use of personal air vehicles.

Bruce Willis’s flying taxi in The Fifth Element (1997, Luc Besson, Columbia/TriStar pictures)

Uber has signed deals with five companies that are developing electric VTOL aircraft, including the Pentagon-backed Aurora Flight Sciences and Bell Helicopter. The idea is that, as with Uber’s car service, you could summon your air taxi with a phone app. A new range of pilotless aircraft — effectively drones — that would fly passengers from A to B could bring the costs down further (though UK air traffic rules require a human pilot to be on board to take over the controls).

In Dubai the authorities have announced trials of an air taxi service using a Chinese-made remote-control drone ’copter, the EHang 184. According to the EHang’s manufacturer, it can fly passengers across the city on journeys of up to 23 minutes, or 31 miles.

One solution to overcrowded skies could be aerial “motorways” that users would follow using GPS. Engineers at Liverpool University, along with counterparts at Swiss and German institutions, have started mapping a network that would let the PAL-V and its ilk fly safely along designated routes. These would be kept away from cities and airports and would fly at 100ft-1,500ft, below the altitude of passenger jets.

Mike Jump, of Liverpool University, said it would be a while before such routes were up and running. “Concept flying cars are often shown flying with clear blue skies [in places such as Dubai or California], but it is not clear to me what would happen in bad weather. ”

His German research colleague Heinrich Bülthoff, of the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, estimates that flying cars are five to 10 years away — still tantalisingly out of reach.

In the immediate future it’s more likely that the first flying cars will be like the Kitty Hawk — for recreational use. That’s how the automobile started out.

Before you rush to invest in what seems to be a new and lucrative technology, however, take a moment to search on eBay. The website is an online scrapyard for great ideas that never quite made it. One is the Moller M400 Skycar (above), which received widespread publicity the last time flying cars were said to be just around the corner, in the 1990s. It never flew without a tether or won FAA approval.

If nothing else, it is a handy reminder that just because something is possible, it does not mean it is going to happen. For anyone interested, the Skycar is still looking for a buyer — suggested price tag $5m.

Flying cars coming to the skies near you

PAL-V Liberty

Price £520,800

On sale Late 2018

How fast can it fly? 112mph

How far can it fly? 310 miles

Top speed on the road? 100mph

How far can it drive? 817 miles

Kitty Hawk Flyer

Price TBC

On sale Late 2017

What’s under the bonnet? Eight electrically powered rotors

Will it fit in the garage? Snugly

How high can it fly? A few feet off the water

Terrafugia Transition

Price £310,000 (estimate)

On sale 2019

How fast can it fly? 100mph

How far can it fly? 400 miles

Top speed on the road? 70mph

How far can it drive? 805 miles

Ehang 184

Price TBC

On sale Late 2018

What’s under the bonnet? Eight electrically powered rotors

How fast can it fly? 62mph

How far can it fly? 23 miles

How high? 11,500ft

Life is imitating art with the DeLorean Aerospace DR-7 flying car

“Where we’re going, we don’t need roads”

When Doc Brown uttered this memorable line in Back to the Future, he was in a DeLorean flying car powered by a Mr Fusion garbage disposal unit. Spool forward in time and fiction could soon be fact. A prototype DeLorean DR-7 all-electric flying car is scheduled to fly next year, according to Paul DeLorean, nephew of John DeLorean, the man behind the sports car of the 1980s.

DeLorean Aerospace, his company, has built two scale models: a small drone-sized one to test the concept and a larger, one-third scale version. Both are said to perform exactly as Doc Brown would have wanted. The prototype will be capable of vertical take-off, so won’t need to reach 88mph on the ground, as the original version of its film namesake did, or require as much as 1.21GW of electricity. Battery-powered propellers, resembling fans, at the front and rear will swivel to provide downdraft for take-off and landing and propulsion during flight, as well as rudderless steering.

With room for two passengers, it will have an estimated range of 120 miles at 150mph, and a top speed of 240mph. The wings will tuck away so the car can fit in a large garage. The craft can be flown manually or by remote control.

The prototype, being built in California, will be 19ft 6in long, with an 18ft 6in wingspan, foldable to 7ft 6in. Sadly it will not have gull-wing doors like the one in the 1985 film, or an OUTATIME numberplate.

Forget Back to the Future’s DeLorean: here are six real flying cars