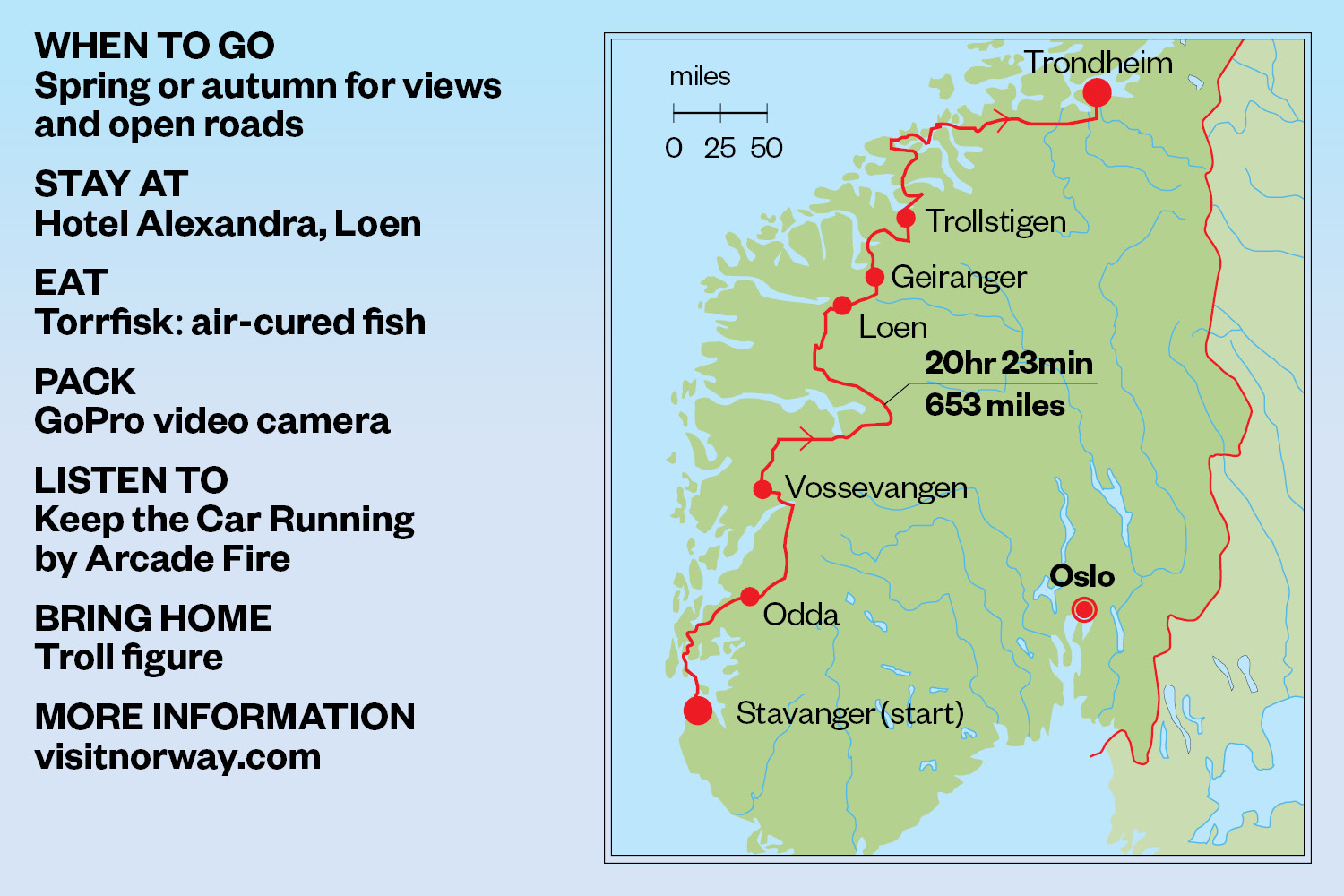

Great Drives: Norway's west coast

On a jaw-dropping road trip up Norway’s west coast, James Mills sees hundreds of fjords, rugged mountain ranges, two record-breaking tunnels — and a road for trolls

IT’S A good job the Norwegians aren’t preoccupied by health and safety. If they were, visitors would find themselves faced with mile upon mile of fencing and signs warning of the dangers of careering off the road and into a fjord.

Such niceties are almost absent on the route from south to north along Norway’s west coast. At times it feels as though someone forgot to turn off a bath tap: the country has nearly 1,200 fjords, providing plenty of opportunities for ferry captains.

The challenge facing road builders must have been immense. Dizzying mountain passes, epic tunnels and jaw-dropping bridges have visitors stopping to fill their social media feeds with snapshots.

The best time of year to visit is spring or autumn: avoid the summer, when camper vans crammed with families and coaches filled with tourists can cause tailbacks that stretch from the start of Trollstigen (Trolls’ Path) to its viewing platform at 2,300ft.

It used to be possible to sail between Newcastle and Stavanger. Plenty of Brits, Norwegians and Swedes would do just that, some ending the voyage distinctly worse off, thanks to the heave of the ocean or the lure of the bar.

Now you have to fly and hire a car, or cross the Channel, hang a left and head for Denmark, where romantics can sail from Hirtshals to Kristiansand in Norway. Fans of the TV series The Bridge simply must see the Oresund Bridge, which connects Copenhagen and Malmo, in Sweden, and features prominently in the show.

I’m in a petrol-powered version of Mazda’s latest CX-3 — a compact SUV that looks like the motoring equivalent of a Norwegian rock climber’s technical training shoe. Its angular lines, wheels pushed out to the corners and low stance give it some attitude and a responsiveness that comes in handy on the more demanding Norwegian routes.

“The awe-inspiring Trolls’ Path is a dizzying stretch of road that puts Italy’s Stelvio Pass to shame”

The roads hug valley sides, dodge waterfalls, rise and fall with mountain ranges and do anything but run straight and flat. The only time you get a smooth run is when crossing a fjord by ferry.

If further proof were needed that the Norwegians aren’t inclined to sit back and let Mother Nature get the better of them, it’s in the road tunnels. The world’s deepest undersea tunnel connects Orsta, on the mainland, to Eiksund, on Hareidlandet Island. At nearly 950ft below sea level, you need to unpop your ears. And it’s essential to select a low gear, or your car will roll away with alarming speed on the steep descent into the tunnel.

Between Vossevangen and Loen is the Laerdal tunnel — the world’s longest road bore. With strange blue lighting and, at intervals, flame effects illuminating the grey concrete walls, it feels like a chillout room from the Ministry of Sound, circa 1995. Along its 15-mile length are lay-bys built to relieve the strain on drivers. Coaches pull over and tourists take photos. I do the same.

Where the fjords are too deep even for Norway’s tunnellers, there are ferries. Bad coffee and questionable-looking sausages are available to travellers who choose to leave their car and venture below deck.

An overnight stay in Loen should include a trip up the Skylift. Rising to 3,300ft, the cable car ride attracts more than tourists: Base jumpers equipped with parasails watch from the viewing platform, waiting for clouds to disperse.

From here, the next highlight is the high-rise views above Geirangerfjord. The nine-mile fjord is a Unesco world heritage site and on one of Norway’s national tourist routes. So it’s worth rising early, before passengers converge on the site from their giant cruise ships, docked hundreds of feet beneath a viewpoint on County Road 63.

Even more awe-inspiring is the aforementioned Trolls’ Path. Open from late spring to late autumn, this dizzying stretch of road puts Italy’s Stelvio Pass to shame, with breathtaking views from platforms that hang off the mountain side. Small piles of stones like cairns are assembled for good luck, and no one grumbles at you for stepping off the pathways to build them — quite the opposite, in fact.

It’s much the same story along the Atlantic Ocean Highway, where you can leave the raised walkways and make your way down to the sea lapping at the granite rock formations. The road snakes off in the distance, linking the small skerries, or islands, with a flurry of bridges.

It opened in 1989, and was partly paid for by tolls. Once the costs had been paid, the tolls were removed — something British drivers no doubt wish would happen at the Dartford Crossing.

The trip ends in Trondheim, Norway’s third city. It is reminiscent of London’s Docklands: everywhere you look there are signs of redevelopment. It feels a good place to relocate, as long as you don’t mind ferries and tunnels.