Great Drives: My way is the highway

California’s Route 1 combines spectacular scenery with the silver screen’s most celebrated locations. Explore the coast with the most

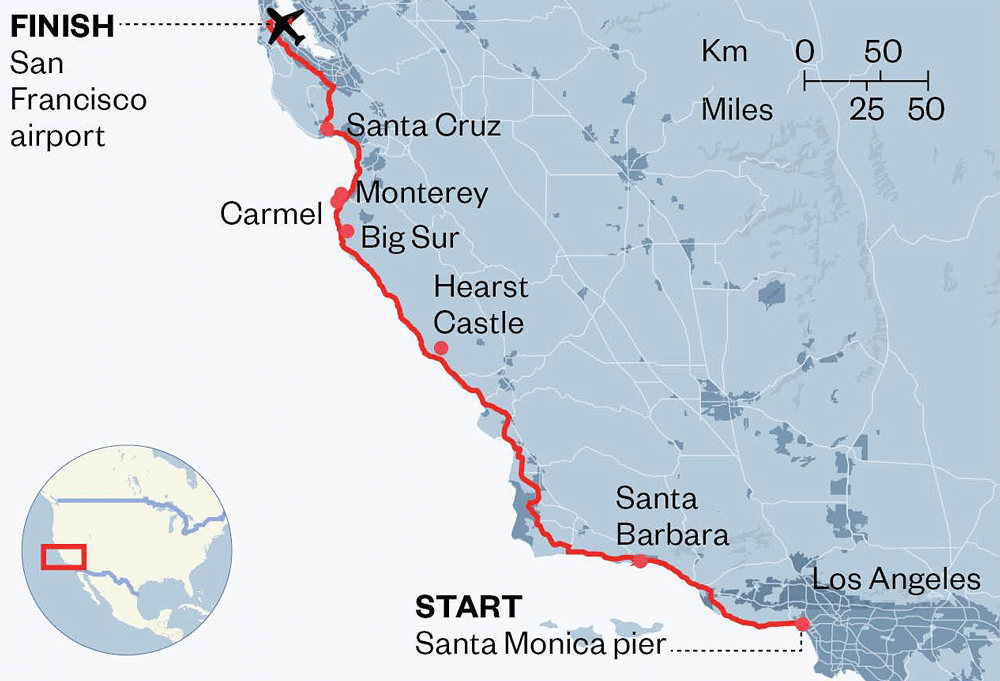

IN A country where scenic routes are common, Route 1 stands out. Stretching more than 500 miles up the Californian coast, it carves through some of America’s most outstanding scenery, along the edge of towering cliffs, past sand dunes and seal colonies and winding through high mountain passes and low-lying vineyards.

You can get lost among the back roads that join it but you’ll always find your way back to the main route. On your left as you head north are the crashing waves of the Pacific, the best navigation aid you could ask for.

At times the road can be slow, especially where it becomes a main thoroughfare through downtown Los Angeles, and in the narrow two-lane section near the rugged coastline of Big Sur, where traffic slows to a crawl in peak summer, but it is never dull. From the surf beaches of Santa Monica to the boardwalks of Santa Cruz, from the old canning factories of Monterey to the bustling boutiques of Los Angeles, it hums with activity.

In strict geographical terms Route 1 starts at Dana Point, about 65 miles south of the LA sprawl. But if you are a visitor from the UK, it starts in the grey drizzle at Heathrow, where odysseys like this usually begin.

As you step out of Los Angeles airport, the cloudless Californian skies and winter sunshine burn away the memories of a 10-hour flight. You wander round a vast parking lot to find your car. Then you weave through the traffic, riding elevated freeways to downtown LA. Rodeo Drive, Sunset Boulevard, Beverly Hills. Place names that sounded so exotic back in the UK are part of the daily grind here, signposted on overhead gantries.

Yet that doesn’t detract from the sense that you’re heading for a promised land. Take the off-ramp to Hollywood, or the expressway to Universal Studios.

The city is not as you might first imagine. The blanket of smog has been rolled back by some of the tightest clean-air laws in the world. Hipsters have moved into many run-down city centre areas and populated the trendy downtown bars.

If you want to avoid the worst of the traffic, head north from the airport to Santa Monica. Art deco oceanfront houses line what is known locally as Palisades Beach Road. Head north, following signs for the Pacific Coast Highway. As the late afternoon sun dips towards the ocean, surfers catch their last waves and the funfair on Santa Monica pier roars like a wounded dragon.

To get the most out of the drive, you’ll need a convertible, preferably with seat warmers and a good heater that can blast away the evening chill. With the top down, the road comes to life — more so than if you are merely watching it through the windscreen of what Americans call a “coop” (that’s where you keep chickens, Jeremy Clarkson once joked).

“It’s on these hairpins that a rear-wheel-drive sports car such as the MX-5 comes into its own”

Before embarking on the 400-mile leg to San Francisco, make sure you leave enough time to acquaint yourself with the novels of Kerouac and Steinbeck. You’ll find yourself pulling over every few miles to admire the views, or to explore the towns along the way.

Santa Barbara is steeped in history. Picturesque Pacific Grove was Steinbeck’s favourite. The gardens of the seaside houses stretch down to the dunes, where beach primrose and purple sage grow in reefs like coral in the salty Pacific air.

In sections, the road merges with Interstate 101, where the little Mazda MX-5 roadster I’m driving is dwarfed by semis — the giant lorries that haul freight between Los Angeles and the Bay City area. In other parts, it’s a spindly two-lane ribbon that wraps around headlands with only dainty crash barriers separating you from the rocks below.

It’s on these hairpins that a rear-wheel-drive sports car such as the MX-5 comes into its own. Out of season, when the road is clear, you can have as much fun as is possible on four wheels, working the gears, brakes and throttle in unison to slingshot between apexes.

Construction of the road began early in the last century but it wasn’t until the 1960s that it was reclassified as a single highway. It thus became inextricably linked with the rootlessness of that era, a route out of the smog for thousands in search of adventure or a better life.

Part of it was a make-work scheme paid for with money from Roosevelt’s New Deal during the Great Depression of the 1930s (hence the sections named in his honour). Vertigo-inducing bridges were built with the help of prisoners from California’s jails, promised an early reprieve in return for sweat and toil.

When mountains got in the way, road workers blasted clean through them, using hundreds of tons of surplus explosives left over from the First World War. A section of road fell into the sea after the Californian earthquake of 1957 and the route was diverted inland. Make sure you avoid the stub of the old route or risk doing as I did in darkness — running out of road with a cinematic screech of brakes and dust cloud, as if in a scene from Thelma and Louise.

Other hazards await the unwary. The appropriately named Devils Slide area south of Pacifica became known as a site of frequent road-closing landslides. Other sections have been unevenly patched up after subsidence or frost damage.

The 100-mile section that approaches Carmel passes a colony of elephant seals (volunteers are on hand to give free natural history tours) and Hearst Castle, the fabulous home built by the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst that became a swinging retreat for Hollywood glitterati in the 1930s.

Allow plenty of time for this trip — three weeks if you can spare it. If you can’t, you’ll have to fast-forward between the highlights. Just make sure you pack your coolest sunglasses, and then prepare for a journey that takes you through the celluloid screen and into your own road movie.