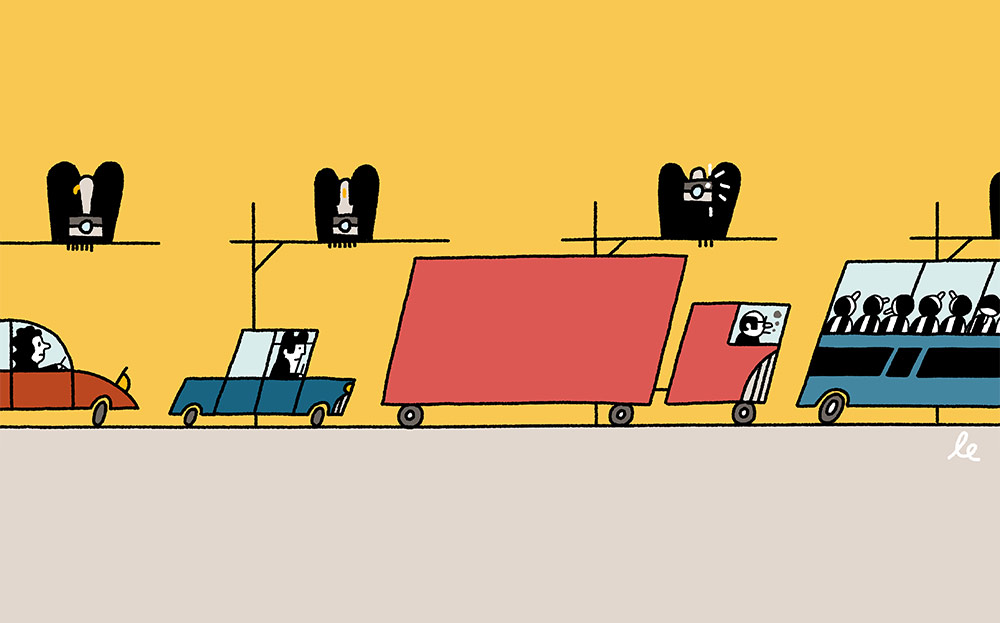

Average speed cameras on the rise despite safety and privacy concerns

Smile: the birdie’s watching

DRIVE west out of London on the A40 at the end of a long hard day, and as the sun sets you may struggle to discern the small speed cameras above the road on spindly gantries. One after another they come, tracking drivers’ average speed over an 11-mile stretch.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

Their predecessors were easy to spot — big yellow boxes that signalled their presence with flashes as they snapped drivers breaking the speed limit. Not any more — today’s cameras do not betray their presence with as much as a flicker.

The A40 average-speed cameras form a new chapter in the story of road surveillance. They were installed last October, and in their first two months of operation the Metropolitan police issued drivers with 1,303 notices of intended prosecution.

The original purpose of average-speed cameras was to protect road workers at motorway contraflows — that was how they were sold to the public — but they are increasingly used for slowing down millions of drivers on vast tracts of ordinary roads. Their widespread use has provoked angry responses from privacy campaigners and single-issue campaign groups.

“Speed cameras are one example of how the modern motorist can be tracked around the country.”

Simon Williams, an RAC spokesman, voiced concern about the unchecked spread of the devices. “Their increased use will inevitably take us further towards a Big Brother-style society where average-speed cameras are ubiquitous,” he said.

Richard Tynan, of the campaign group Privacy International, said: “We’re uneasy about the capability of speed-camera technology, today and in the future. Speed cameras are one example of how the modern motorist can be tracked around the country.”

North of the border the A9 average-speed camera scheme runs from Dunblane to Inverness, a distance of 140 miles. It is Europe’s longest and hasn’t gone down well with many residents.

Mike Burns, an IT engineer who lives in Foyers, near Inverness, set up a Facebook protest group called “A9 average speed cameras are not the answer” after plans for the scheme were announced: Transport Scotland said more than 100 average-speed cameras would be installed at a cost of £2.5m. Within days of being set up, the group had attracted more than 4,000 likes and 16,000 views.

“It is an ill-thought-out plan and doesn’t address the fundamental problem of the A9, which is primarily bad driving and frustration,” Burns said at the time.

Today, 18 months after the cameras were switched on, he is claiming vindication, after the release of official figures showing that from when the cameras were switched on to March 2015 the number of fatal accidents was higher on the Perth-to-Inverness stretch of the A9 than the average for the same period in the preceding three years.

“It shows the system has failed completely on that stretch,” Burns says. Figures for the first full year of operation, however, show a fall in the number of accidents.

The cameras that Burns and his fellow campaigners object to are called Specs. Linked electronically, they use automatic numberplate recognition technology to track vehicles as they pass. How long, critics ask, before these cameras are routinely installed on motorways, where they would be a cheap alternative to enforcement by traffic police, and arguably more practical (because fewer would be required) than fixed cameras of the Gatso type?

Britain’s first Specs camera was installed in Nottingham in 1999. The devices have spread to more than 100 locations, monitoring almost 400 miles of road. About 30 installations are temporary, at roadworks on motorways and main roads.

What concerns campaigners such as Burns is their use as a permanent speed-control measure on roads such as the A9 that are clear, or largely clear, of roadworks. There are 74 such setups. Last year more were established than in any previous year, and their number is set to grow still further.

For the past two years Ken Gardner’s journey to work in St Neots from his home in Huntingdon has taken him along a stretch of the A1 in Cambridgeshire monitored by average-speed cameras. The cameras, which cover two miles between Buckden and Southoe, were installed by Highways England in March 2014 at a cost of £1m to enforce a 60mph speed limit.

When the cameras were switched on, Gardner wrote to The Sunday Times expressing his concerns. “Motorists drive along between cameras at high speed, then slam their brakes on as they approach the next one,” he said. “Others suddenly realise they have been going too fast and slam their brakes on to bring down their average speed between cameras.”

Today Gardner, who owns a satellite communications company, accepts they have solved some problems but says they have created others.

“Regulars are used to the cameras now and have modified their behaviour, but other drivers still come hammering down, see the cameras and slam on their brakes at the last second, causing other drivers to panic and do likewise,” he says. “I’m convinced there are still people out there who do not understand the concept of average speed.”

“We install them only when other solutions, such as re-engineering the road, have been explored. They are not our default choice”

Last month the Commons transport select committee published a report on road traffic enforcement. David Davies of the Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport Safety told the committee that average-speed cameras were becoming more acceptable to drivers and singled out the A9 as having benefited from them. “The A9 scheme has seen safety and traffic benefits that so far seem to have been substantial,” he said.

Transport Scotland claims the cameras have markedly improved safety. “In the first year of operation, from November 2014 to October 2015, no one was killed or seriously injured on the A9 between Dunblane and Perth,” it says. “The number of fatal and serious accidents between Perth and Inverness was down by almost 45%, with fatal and serious casualties down by almost 58%.”

The transport committee said that if enforcement was to be effective as the number of traffic police continued to fall, the use of technology was essential.

Highways England, which maintains 23 permanent average-speed camera sites where no roadworks are in operation — others are run by police and councils — says the cameras are more effective than Gatsos.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

“There is much higher driver compliance with Specs than with conventional speed cameras,” it says. “However, we install them only when other solutions, such as re-engineering the road, have been explored. They are not our default choice.”

There are signs that drivers’ patience is wearing thin. Burns isn’t giving up on his battle to persuade Transport Scotland to reconsider the A9 cameras. “Traffic has slowed to the extent that people avoid the A9 altogether, or consider whether to make their journey at all,” he says. “These average-speed cameras are throttling our economy.”

Transport for London, which ordered the cameras on the A40, says it expects them to prevent 31 deaths or serious injuries over the next three years.

However, Murad Qureshi, a member of the London assembly, expresses concern that they were installed with little warning and appear to be a revenue source for the Treasury.

“It does appear to be a cash cow for the authorities, and it’s not obvious at all that the change [from the old fixed-speed cameras] has been made.”