Cars’ frugality fuels fear of new tollroads and road pricing

Tolls tomorrow?

DRIVERS HEADING to or from Kent on the eastern edge of the M25 may be in for a pleasant surprise next month. Rather than hitting a tailback at one of Britain’s most notorious bottlenecks, traffic is expected to flow smoothly on the Dartford crossing.

Search for and buy your next car on driving.co.uk

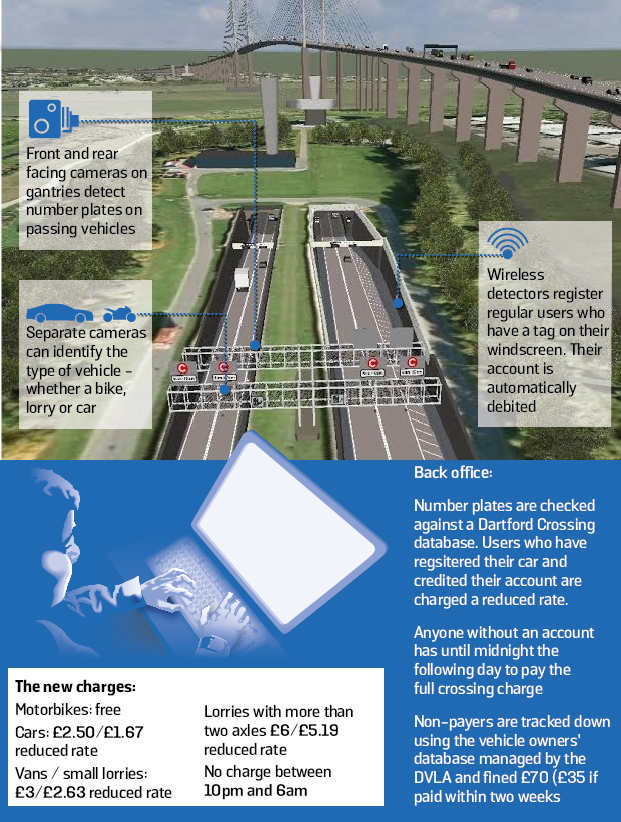

The reason is that the toll booths are being replaced with a system under which there is no need to stop and pay a cashier. Instead, overhead cameras will record numberplates and save them to a central database. Drivers must pay by midnight the next day or set up an account that will deduct the fee.

It’s good news for commuters, and will thwart tail-gating toll cheats. But behind the free-flowing traffic could lurk a more sinister development for millions of motorists: the prospect of road charging being introduced across Britain.

Despite official denials, the suspicion remains that the cameras and charging infrastructure on the Dartford crossing are a testbed for road tolls that could be used elsewhere. Buried in the 2012 Dartford contract tender issued by the Highways Agency, which looks after Britain’s main roads on behalf of the government, was the requirement that the technology be capable of being applied on other roads.

Despite official denials, the suspicion remains that the cameras and charging infrastructure on the Dartford crossing are a testbed for road tolls that could be used elsewhere

The system, said the contract, “may also allow Dartford [account holders] to use other road-user charging and/or tolling schemes, and have the charge or toll taken from their Dartford account.” The contract was won by Sanef, a French company that operates many similar systems on France’s motorway network.

The fact that road charging appears to be back on the agenda will surprise many drivers. Although the scheme has been mooted for years, no government has been able to persuade the electorate to accept it. In fact, in Westminster toll charges have become a toxic subject. The Labour government developed plans for national road tolls and encouraged councils to introduce their own road-pricing schemes. But voters in Manchester and Edinburgh rejected such policies and Labour dropped it in 2009 after 1.8m people signed a petition.

The coalition government tried a different tack: allowing new roads to charge tolls to attract investment. Some believe that plans are being drawn up.

Contained in the innocuous-sounding Infrastructure Bill, announced in the summer and now going through parliament, is a plan to spin off the Highways Agency from government control. Although still funded by the Treasury, it would to all intents and purposes be a private firm. The move would make it easier for the government to sell off the agency in the way that it has sold other public utilities such as the Royal Mail and is selling its stake in Eurostar. Once it is sold, its private owners would be free to raise revenue via road tolls, while the government could distance itself from the decision.

“We firmly believe that this [bill] is the final stage before privatisation of the strategic road network, and once the network is privatised, toll roads will follow to provide revenue for the companies that run them,” says Mark Dollar, a Highways Agency employee and leader of the Public and Commercial Services Union’s action group that is opposing measures in the bill.

“The roads minister has said that there are no plans in this parliament or the next to privatise the roads, but it is clear that Britain’s largest public asset, worth £111bn, is being fattened up for sale. Tolls may happen even earlier as the government tries to prove that they can be made to pay for themselves.”

“We firmly believe that this [bill] is the final stage before privatisation of the strategic road network, and once the network is privatised, toll roads will follow to provide revenue for the companies that run them”

Robert Goodwill, the roads minister, has denied there are any plans to sell the agency. Government documents suggest that instead it will be funded by a Department for Transport (DfT) grant, renewed every five years. Yet the Public and Commercial Services Union points out that recent appointments to the agency’s board include Tom Smith, the former chief executive of the M6 toll road, and Elaine Holt, who previously led the East Coast public sector rail franchise, to be reprivatised next year.

One thing seems certain: the subject won’t go away. And the reason for that is cash. The fear is that as cars become more fuel-efficient, drivers will pay less in fuel tax and road tax, leaving the government with a black hole in its finances. According to one projection from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the combined effect will leave the Treasury with a £13bn shortfall (in today’s money) by 2029.

In fact figures released by the Treasury reveal that revenues have already started to fall. Last year 63% of new cars were exempt from their first year of road tax, thanks to their low CO2 emissions. In five years’ time, the chancellor expects to collect £5.4bn from the tax, down from £6.1bn in the last financial year. The amount collected in fuel duty is expected to increase from £26.8bn to £29.8bn, but this represents a fall in real terms.

Search for and buy your next car on driving.co.uk

Economists, motoring groups and analysts believe road tolls will be needed to fill the gap. “Fuel-duty revenues are gradually disappearing and there is a question: what are you going to replace them with?” says Stuart Adam, a senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

“We have a tax on motoring that is shrinking that we would like to replace. There is also a very good economic argument for taxing congestion and you might therefore make the link between the two — why not introduce a proper national system of road pricing that would replace most of fuel duty? It would not be politically easy but I do think economically it’s the right thing to do.”

A report on enforcement technology, commissioned by the Highways Agency and published by the Atkins consultancy earlier this year, was equally stark. “Cars are getting more efficient, public transport is becoming more popular, alternative modes are becoming more acceptable, all of which points to a loss of tax from fuel,” it said. “There may be pressure in the future from the Treasury and local authorities for the Highways Agency to work in concert with local authorities to achieve tolling aims.”

Estimates drawn up by the DfT in 2004 said road pricing would cost between £3.1bn and £7.3bn a year to run but generate £12bn in revenue. In 2007 the RAC Foundation estimated that a national tolling scheme could generate as much as £25bn.

The government points to the cancellation of the planned A14 toll road as evidence of its wariness of charging drivers. “The A14 sent out a very clear signal: we do not intend to invest in funding new road projects by tolls. There is no secret plan that after the election we will do a U-turn and ask people to pay for roads,” Goodwill told the transport select committee in February.

In 2007 the RAC Foundation estimated that a national tolling scheme could generate as much as £25bn

Not everyone believes his views will prevail. In May the Institute for Public Policy Research published a report, The Long Road to Ruin, calling for a pay-as-you-go system. “Steps to reform fuel duty and [road tax], and to create a progressive system based upon road usage, are urgently required,” it said.

Vince Cable, the business secretary, recently argued that new sources of revenue were needed. “Any politician who tells you that the next government can balance the budget and avoid tax increases is lying to you,” he told the Liberal Democrat conference. While politicians squabble, money and time are running out for Britain’s roads: a radical rethink is overdue.

As drivers cruise over the Dartford crossing next month they should spare a moment to glance at the cameras overhead. They might be seeing more of them, sooner than they think.

From Rome to Dartford: toll roads through the ages

Toll roads have existed since the Roman empire and in Britain became common in the 17th century (the term “turnpike”, as in Turnpike Lane, refers to the practice of placing a pikestaff across a road to block passage. It would be turned to one side to allow travellers through once the toll had been paid).

By the 18th century such charges applied to a fifth of Britain’s road network, controlled by turnpike trusts, which were allowed to impose tolls in return for repairing and maintaining routes.

From the 1950s new technology began to make pricing on the entire road network feasible. One of the first hi-tech schemes was proposed by two academics at the University of Chicago. The plan was to introduce road markings using radioactive paint. The most popular roads would be the most radioactive. A Geiger counter fitted to each car would record its exposure to radiation and drivers would be charged accordingly.

The concept didn’t catch on, perhaps unsurprisingly. Modern plans appear to be no less toxic — politically at least.

Read one man’s DIY toll venture heading for £300,000 target

Search for and buy your next car on driving.co.uk