Caterham Tracksport: in search of my inner racing driver

Look out, Lewis. I’m hard on your heels

ACCELERATE OUT of Redgate and look down the Craner Curves at Donington Park. This is where Ayrton Senna went round Michael Schumacher in 1993 on his way to probably his greatest grand prix victory. Grab fourth gear, stay hard on the power and be as smooth as possible as the little Caterham Seven squirms through the left-hand kink. The speedo touches 110mph.

As I roar past the pits, the reality of what I am doing is beginning to sink in. And things are only going to get tougher. For better or worse, I have decided to find out what it takes to be a racing driver, and as the new season approaches, I can’t help but wonder what I have let myself in for.

It is not just the thrill of racing that has led me here: it is the thrill of driving. Like vinyl records in a world of MP3 files and music streaming, back-to-basics driving is having something of a moment. Amateur racing series featuring vehicles stripped of modern driving aids — such as the Caterham Seven — are enjoying a surge in popularity.

Organisers put that down to the fact that many drivers of a certain age (between 35 and 50) are rebelling against the button-pressing driving of modern cars and searching for something more visceral and real.

That’s certainly true for me, although this is not, in fact, my first time behind the wheel of a racing car. In the late 1990s I entered the Caterham Scholarship event for novice racing drivers, and I’ve done a few one-off events in other cars, but I’ve never competed in a proper season of racing — until now.

This year, with the backing of The Sunday Times’s Driving website, I’ve entered the Caterham Tracksport Championship, and I’m at Donington Park in Leicestershire for the first pre-season test, run by BookaTrack. The championship is aimed at the thousands of drivers who, like me, have always dreamt of racing but never quite managed to do it.

It is one of a series of championships, catering to drivers with differing levels of experience. Those who’ve never raced before start in the Academy; from there you can climb through Roadsport, Tracksport and Supersport to the Superlight R300 Championship, which is for those with lots of money and serious aspirations.

I’ve entered Tracksport, and everyone I’m racing against has at least two years’ experience. (In the best motor sport tradition, I’m getting my excuses in early.)

The Caterham Seven Tracksport I will be driving is perfect for this sort of amateur racing. It can trace its origins to the Lotus Seven of 1957. Caterham bought the rights to the car from Lotus in 1973 and has refined it ever since. It’s the automotive equivalent of the street sweeper Trigger’s broom from Only Fools and Horses: it may look the same, but every part has changed.

It’s not hard to see why the Caterham Seven is popular with novices. It is reassuringly simple both to drive and to fix but looks and feels like a proper racing car. Careful policing of the regulations ensures that everyone competes on an equal footing.

The key to the Seven’s appeal has always been its simplicity. There’s a 1.6-litre Ford engine in the nose, linked to a five-speed manual gearbox originally designed for a Ford Sierra. The engine develops 125bhp, which doesn’t sound much, but even with me on board the Tracksport weighs only 600kg, about half as much as a basic Volkswagen Golf. It has rear-wheel drive and no driver aids — not even antilock braking.

It’s not hard to see why the Caterham Seven is popular with novices. It is reassuringly simple both to drive and to fix but looks and feels like a proper racing car.

The cockpit is brutally basic but not designed for the vertically gifted. I’m 6ft 4in, and to squeeze me in we had to rip out the seat and make a moulding from builder’s expanding foam: I sat in the car and pretended to drive while a Caterham technician sprayed gunk into black bin liners beneath my legs. The process took about four hours, but at least now I’m comfortable and, with the help of a six-point safety harness, safely pinned to the car.

This isn’t Formula One, so no one has an army of technicians to care for their every need. You can hire a team to take care of everything for you (for about £15,000 a year), but most people either spanner the car themselves or call on a couple of friends for help.

I’ve plumped for the latter and am being ably assisted by Chris Ratter and Andy Price from Xceed Motorsport, based in Northwich, Cheshire. Chris was part of the Race2Recovery team of injured servicemen who finished the Dakar Rally earlier this year and is more than handy with a torque wrench.

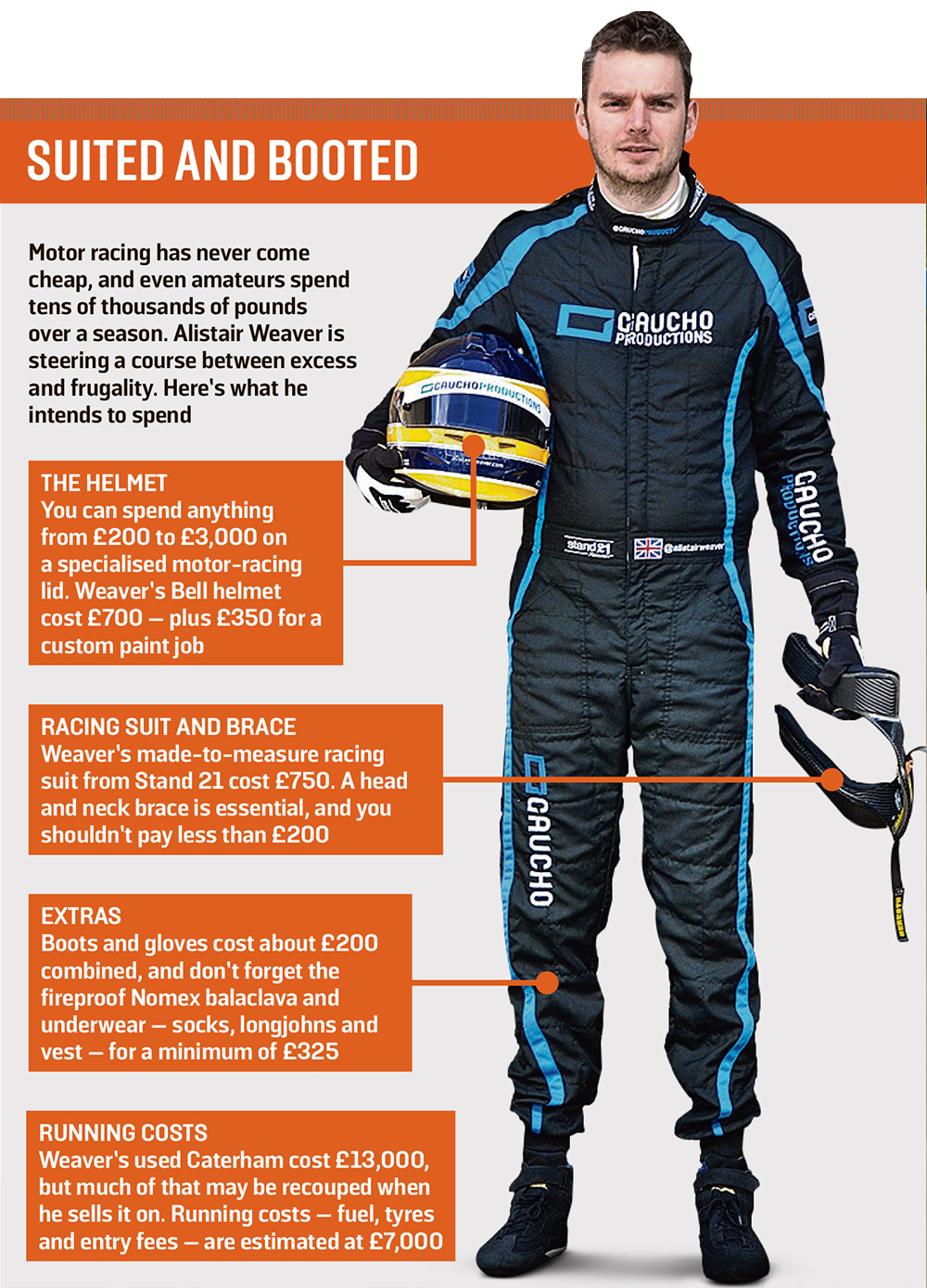

Most of my fellow competitors are middle-aged professionals living the dream, and the championship is devised to be as cost-effective as possible. My car dates back to 2008 and is worth about £13,000. You need a racing suit, a helmet and a Hans neck support to compete, which you should be able to pick up for about £1,000 in total, though I’ve spent a bit more (see panel).

Then there are the race and championship entry fees, tyres, fuel, testing, travel and subsistence costs. If you transport the car yourself and you don’t crash, these should amount to about £7,000 over a season.

That’s a sizeable chunk of cash, but in motor sport terms it’s decent value. Some competitors can simply write a cheque; others, like me, have secured sponsorship. Composing a pitch document and begging for money is all part of the motor sport game, but it helps if sponsors also bring expertise. One of mine, MFT, is a specialist in military-style fitness training and mental preparation.

Right now, as I head onto the circuit, I’m most worried about being off the pace. There’s so much to learn. The season is split into 14 races over seven weekends at circuits such as Silverstone, Brands Hatch, Rockingham and even Zolder in Belgium. Each race is half an hour long and can have as many as 30 identical cars on the grid, so the action is frantic.

Over the course of the six months I’ll be bringing you news of my progress on Driving (driving.co.uk) and describing what it’s like to compete. You will be able to check out the action online via video clips and the Racelogic Video VBox system, which analyses my driving in real time.

Like so many enthusiastic amateurs, I know I’m too old, too tall and too fat to be an F1 driver, but I still want to know if I have what it takes. Am I grand prix’s great lost talent, or just a hopeless dreamer?

Where to catch the Caterhams

The Caterham Tracksport championship kicks off this weekend with two races

at Snetterton and continues until October. Follow Alistair Weaver’s progress here on driving.co.uk, complete with video and GPS data from his car after each event.

April 19-20 Snetterton, Norfolk

May 10-11 Donington Park, Leicestershire

June 7-8 Circuit Zolder, Belgium

July 12-13 Rockingham, Northamptonshire

August 2-3 Brands Hatch Indy, Kent

September 6-7 Croft, North Yorkshire

October 18-19 Silverstone International, Northamptonshire