What drivers need to know about government diesel scrappage and nitrogen dioxide reduction

Taking action against toxic emissions. Maybe.

THE DEPARTMENT for Environment & Rural Affairs has published a consultation document outlining the government’s proposals for reducing harmful nitrogen dioxide (NO2) created by diesel engines.

Many of the estimated 40,000 premature deaths every year in Britain from toxic air are caused by illegal levels of nitrogen oxides and particulate matter found in emissions from diesel cars, vans, buses and coaches. As a result, the government has been under pressure to act without delay in cleaning up the air.

However, many motorists have been concerned after talk of punitive action against drivers of diesel vehicles, particularly since the popularity of the fuel is attributed to the tax incentives of previous governments, which encouraged the take-up of diesel vehicles in order to reduce carbon dioxide levels associated with petrol engines.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

As a result, the number of diesel cars in the UK has exploded in the last 20 years; in 2000 there were 3.2m on the roads but in 2010 this figure had risen to 8.2m, according to the Department for Transport. Over the same period, the number of diesel vans rose from 1.8m to 3m.

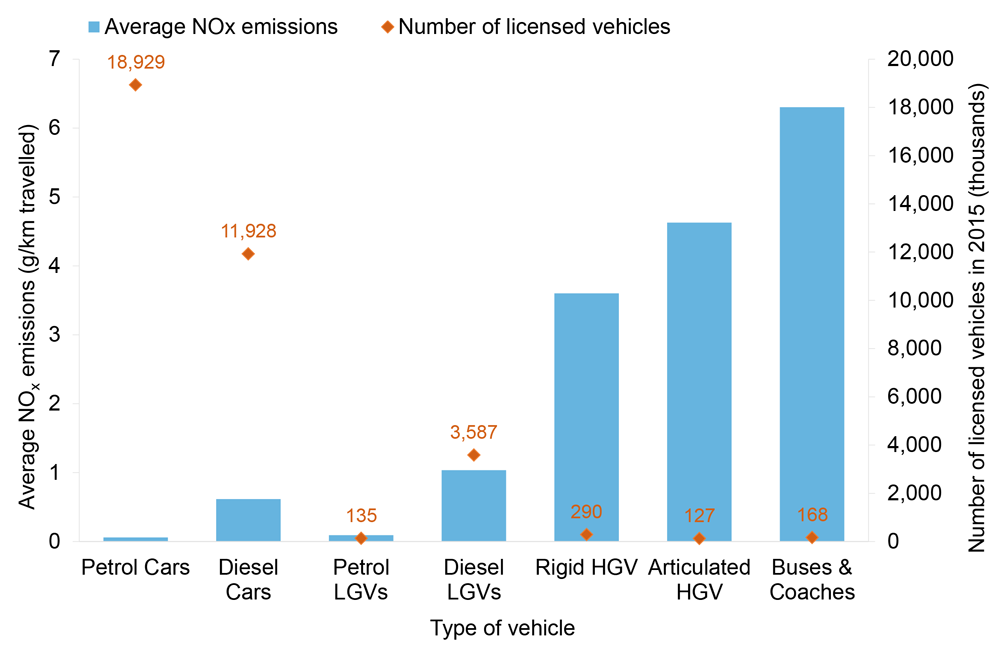

Average nitrogen oxides emissions by vehicle type (grams/kilometre) and number of licensed vehicles in 2015 | Source: DEFRA

The current Conservative government had hoped to delay publication of its plans until after the general election on June 8, but lost a court battle to keep the proposals under wraps and so today the draft proposals were released. Here’s what drivers need to know.

These are only draft proposals

It’s important to remember that the plans are at the draft stage and the government is inviting feedback until mid-June, ahead of the six-week consultation process.

A “Clean Air Zone” could be coming to your town

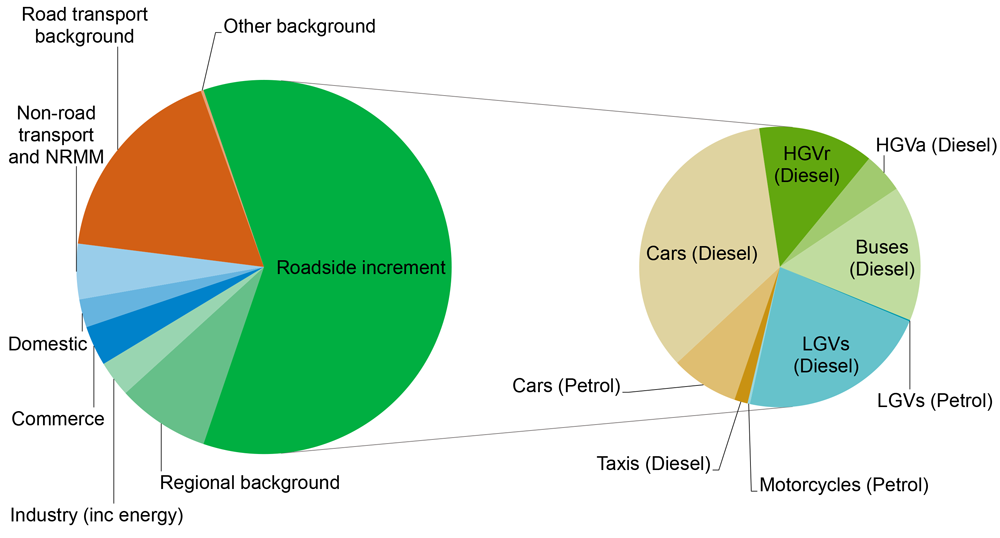

A proposed UK Air Quality Plan will see the introduction of “Clean Air Zones” around the UK. While central government is creating the framework for the zones, and will support them with funding, local authorities will have responsibility for how they operate.

A Clean Air Zone could involve a number of things, from funding the “retrofitting” of dirty vehicles (see below), to encouraging the use of public transport and bicycles, and even redesigning road layouts to improve traffic flow; for example removing road humps.

Local authorities may also introduce charging schemes to restrict the dirtiest vehicles from entering the area. However, the proposals suggest this should be a last resort, and must be shown to help meet air quality rules in the shortest possible time.

Charging drivers to enter Clean Air Zones is not favoured because older (and, therefore, usually dirtier) vehicles are disproportionately owned by the less affluent, so it has a more significant impact on the poorer members of society. The proposal document states that the government wants to deliver legal obligations on air quality as quickly as possible but that, “this must not be done in a way that unfairly penalises ordinary working families who bought diesel vehicles in good faith as a direct result of tax changes.”

The cities already ear-marked by the government as requiring Clean Air Zones are Birmingham, Leeds, Nottingham, Derby and Southampton, but more recently, local authorities in Greater Manchester and Bristol and South Gloucestershire have secured funding for their own zones.

London is one of the worst areas for poor air quality. According to a 2014 Public Health England report, polluted air in inner London alone is responsible for 7.2% of deaths. As a result, the capital already has a number of plans in the advanced stages of preparation.

Central London will start charging drivers for emissions, on top of the exisiting Congestion Charge. The emissions surcharge, known as the “T Charge”, will target older vehicles and will come into force from October 23, 2017. This will be replaced in April 2019 by an even tougher scheme known as the ULEZ (Ultra Low Emission Zone). You can find out all about the London emissions charging schemes here.

In addition, the London Mayor plans five low emission neighbourhoods spanning eight boroughs, twelve low emission bus zones in Greater London, along with the phasing out or pure diesel buses and a commitment to only purchase hybrid of zero-emission buses from 2018, while no new diesel taxis will be licensed from January 1, 2018.

Where Clean Air Zones are not possible, such as on the “less than 1% of the strategic road network” including motorways and major A-roads, where NO2 levels are projected to persistently exceed legal limits, the government will “identify and implement targeted measures” such as improving the electric vehicle charging network.

There might not be a diesel scrappage scheme

There isn’t a commitment to a diesel scrappage scheme in the draft proposal document. This is what it says:

“Some have suggested that a targeted scrappage scheme for older, more polluting vans or cars could be developed to contribute to the cost of purchasing a cleaner vehicle. Such a scheme would have to be targeted at those most in need of support and be limited in scope. In devising mitigation measures, it will be important to consider the viability of any scheme and its overall cost. If, following this consultation, scrappage is identified as an appropriate mitigation measure, any scheme would need to provide value for money, target support where it was most needed, be deliverable at local authority level and minimise the scope for fraud.”

So while diesel drivers could face a “targeted” scrappage scheme, in which owners of the most polluting cars in the most populated areas would be paid to scrap their cars, this is still to be decided.

In 2009, a £300m vehicle scrappage scheme was introduced that applied to all old vehicles. Owners had to have owned the vehicle for more than 12 months and it had to be more than 10 years old. In return for scrapping their car or van, owners were given £1,000 from the government towards a new vehicle, and participating manufacturers agreed to also provide £1,000 off the list price. A new scrappage scheme for diesel cars could take a similar approach.

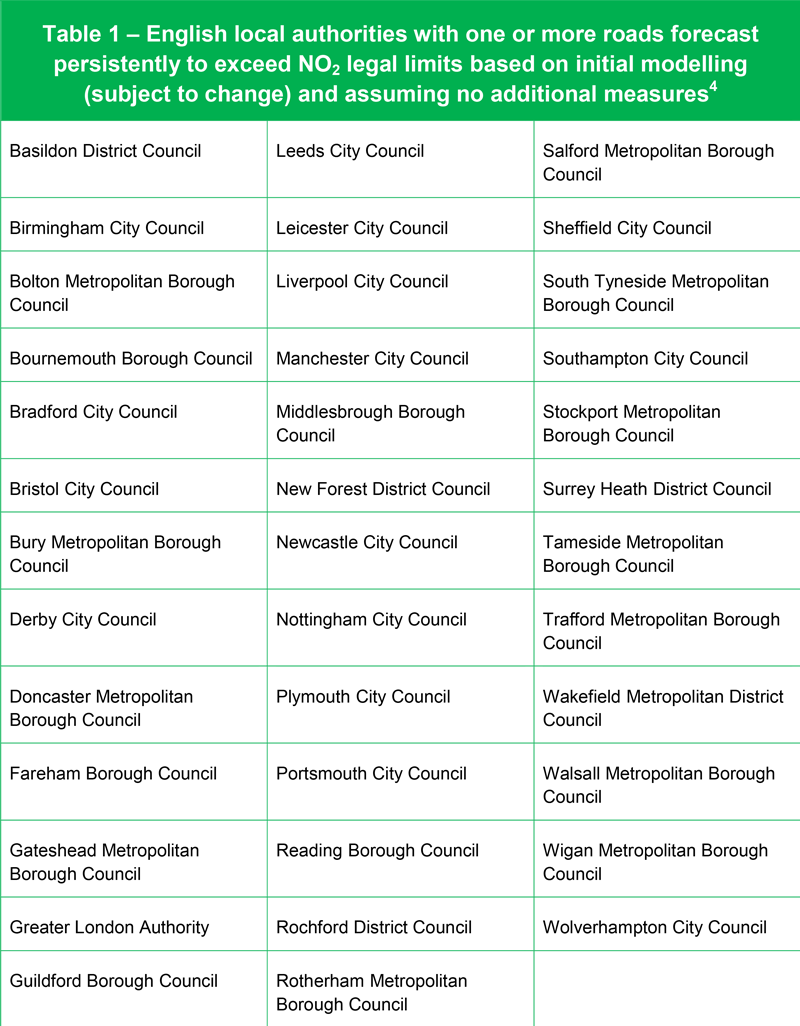

Comparison of nitrogen oxides emissions for different car Euro standards, by emission limit and real-world performance (grams/kilometre) | Source: DEFRA

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has already urged the Government to reintroduce a scrappage scheme in London for older diesel vehicles only.

Under the mayor’s proposed scrappage scheme, van drivers in London would be given £3,500 towards the cost of a cleaner model, and low-income households could receive a credit worth £2,000 that they could use on alternative transport, such as joining a car pool, or on a new vehicle.

The overall cost of London’s plan is estimated to be over £500m, suggesting a nationwide scheme would be prohibitively expensive, which could explain the government’s hesitation of such a scheme at this stage, as the taxpayer (and voter) ultimately foots the bill.

The dirtiest diesels could be “retrofitted”

The government suggests that it could provide funding to “retrofit” the dirtiest diesel vehicles with devices to clean up exhaust emissions. In particular money could be diverted to local authorities to tackle air pollution from buses, taxis and lorries. More advanced diesel particulate filters can be fitted and chemical additives in the exhaust can convert harmful gases into harmless ones, for example.

While there was a commitment to retrofitting buses with emissions equipment, in the Autumn Statement last year, with money provided from the National Productivity Investment Fund, no further detail is provided in the May 2017 NO2 reduction proposal document.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

In 2014 Driving reported that thousands of diesel cars and vans are being driven illegally after having factory-fitted exhaust filters removed. Backstreet garages and some larger dealers are offering to remove the filter systems, which can clog up after about 80,000 miles and can cost up to £1,500 to replace, for as little as £300. Stop-start driving in urban traffic can lead to the filters becoming blocked much more quickly.

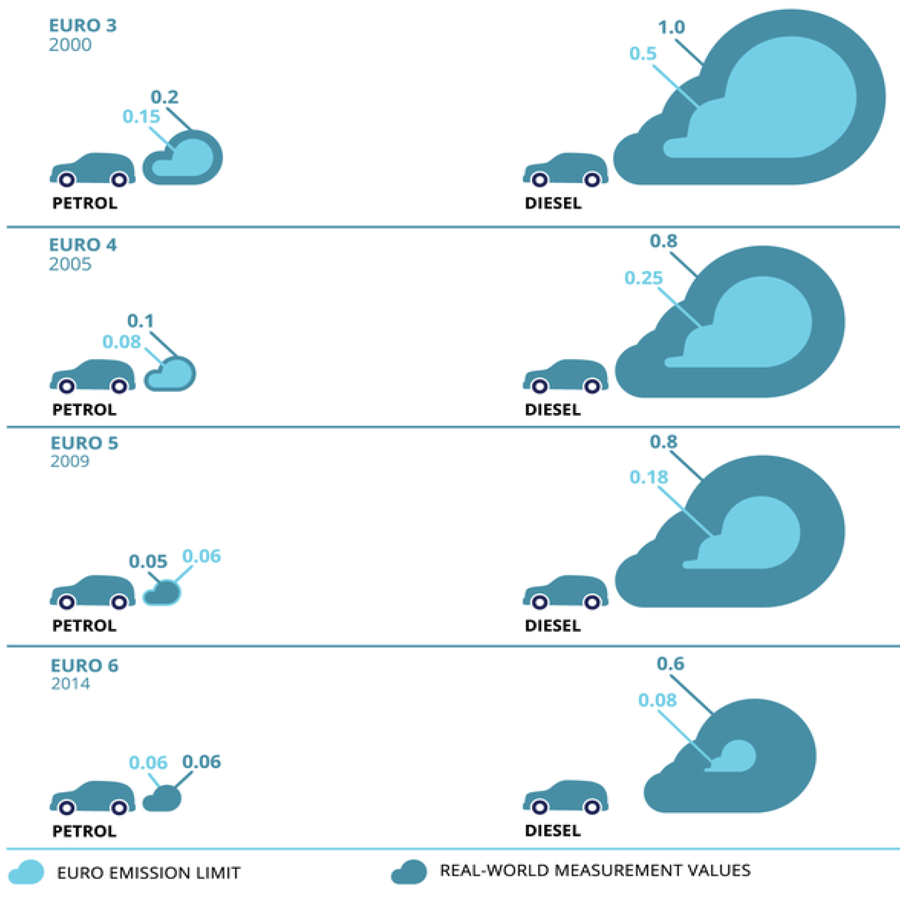

Breakdown of UK national average roadside concentration of nitrogen oxides (includes primary nitrogen dioxide and nitric oxide, which is converted to secondary nitrogen dioxide in the atmosphere) into sources, 2015 | Source: DEFRA

Last year Driving highlighted the decision to end roadside emissions testing, which is the only viable way to police the removal of emissions filters. It is possible that cars and vans could be retrofitted with modern exhaust-cleaning devices using government incentives, only to have the devices removed immediately afterwards as a cost-saving exercise by the owner.

For some it may make financial sense to buy a clapped-out vehicle that has just scraped through its MoT in order to qualify for retrofitting.

Road tax is being reviewed again

The recent Vehicle Excise Duty (road tax) changes, which came into effect on April 1, have been controversial to say the least. Critics argue that they penalise the cleanest vehicles as, from year two, there is a flat tax rate for most vehicles, regardless of emissions levels. Alternatively-fuelled vehicles, such as hybrids, save just £10 a year, so owners of a Ford Mustang V8 would pay only slightly more than owners of a Toyota Prius.

In addition, the first year tax rate is still based on carbon dioxide and doesn’t take into account levels of toxic nitrogen oxides and particulate matter.

There is an indication in the NO2 draft proposals that the tax system could be revised again to address this, however. It states: “As announced at the Spring Budget 2017, the government will continue to explore the appropriate tax treatment for diesel vehicles, and will engage with stakeholders ahead of making any tax changes.”

The government plans to also “launch a call for evidence”on updating the HGV Road USer Levy, aiming to reward hauliers “that plan their routes efficiently.”

Supporting low and ultra-low emission vehicles

As part of the Clean Air Zone initiative, local authorities will be tasked with supporting the take-up of ultra-low emission vehicles, such as pure-electric or hydrogen cars, by adding them to their own fleets and expanding their electric car public charging networks.

Hydrogen cars got a boost in March with the announcement of a new £23m fund to “accelerate the uptake of hydrogen vehicles and roll out more cutting-edge infrastructure”.

A competition will be launched in Summer 2017, with hydrogen fuel providers able to bid for funding in partnership with organisations that produce hydrogen vehicles to help build high-tech infrastructure, including fuel stations. The government says it will match funding for successful bidders.

In addition, the government recognises that 96% of vans are diesel-powered, and that they spend much of their time driving around towns and cities, so it has outlined three possible ways it could encourage a switch to alternatively-fuelled vehicles:

- Increasing the weight limit of alternatively-fuelled vans that can be driven on a category B (standard car) driving licence in the UK, above the standard 3.5-ton maximum.

- Exempting certain alternatively-fuelled vans from goods vehicle operator licensing requirements in Great Britain

- Roadworthiness testing for electric vans in Great Britain

This implies a more relaxed approach to standards for those driving electric vans.

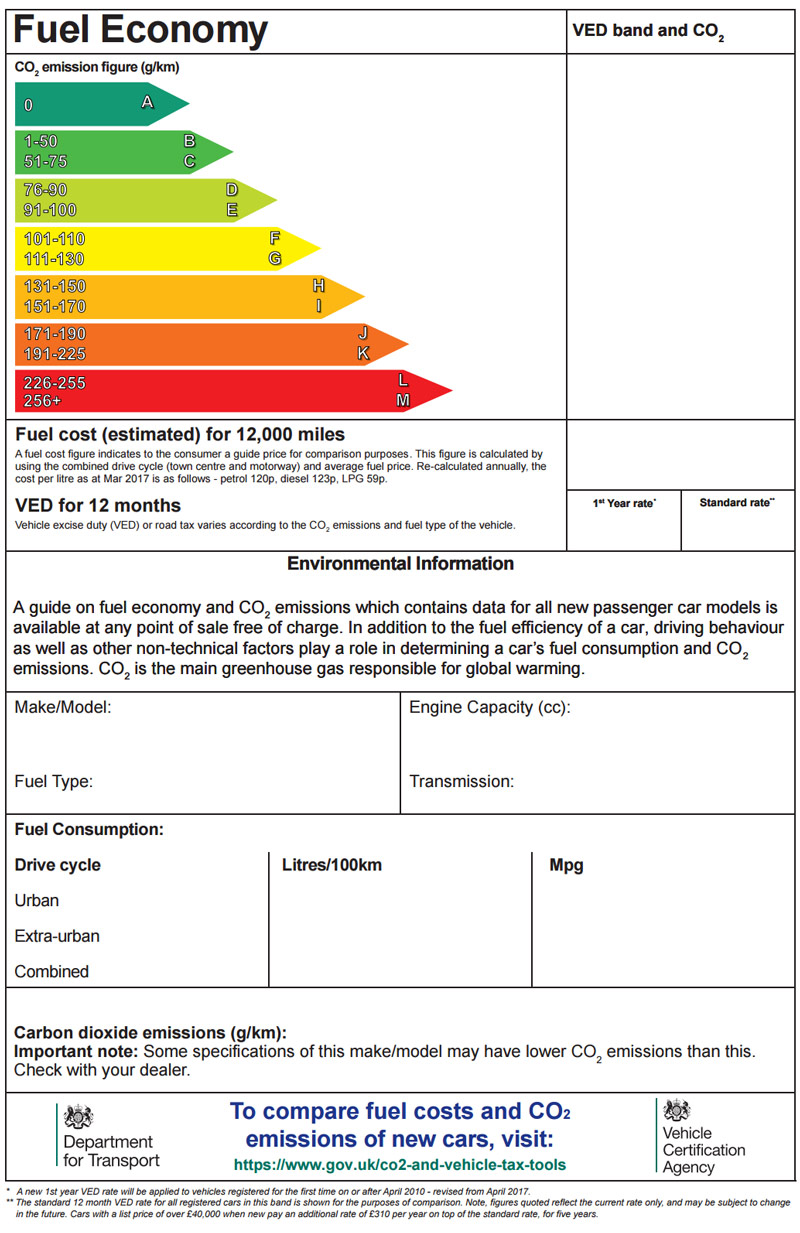

New vehicles could get NO2 labels

New vehicles come with stickers that show their fuel economy and carbon dioxide emissions levels, which (as illustrated) determines road tax in the first year. However, the government is conducting a review of vehicle labelling supported by the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership, to consider the most appropriate way to give consumers the information that they need, and this could include the addition of NO2 information.

New vehicles come with stickers that show their fuel economy and carbon dioxide emissions levels, which (as illustrated) determines road tax in the first year. However, the government is conducting a review of vehicle labelling supported by the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership, to consider the most appropriate way to give consumers the information that they need, and this could include the addition of NO2 information.

This work should be completed within a year and the results will be fed into the UK Air Quality Plan for tackling nitrogen dioxide.

Tougher standards for diesel generators and machinery

Tougher emissions tests for vehicles come into effect from later this year, focussed on “real-world driving emissions”, but the government also plans to have tighter controls on emissions from “medium combustion plants” and diesel generators. It plans to enforce these from the end of 2018.

Getting tough on “red diesel”

Many drivers may not be aware but not all diesel costs the same. Because much of the industrial backbone of Britain runs on diesel, including agricultural and construction machinery, and some people rely on diesel for heating, “red diesel” can be purchased specifically for these purposes at costs greatly below those found at petrol stations.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

There is no difference between red diesel and diesel used to power road vehicles except that a red dye is added to allow police and the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) to identify it in vehicles. Potentially, a diesel driver could save thousands of pounds a year running red diesel instead of regular diesel. However, if caught using red diesel illegally, drivers face fines and could have their vehicle impounded or crushed.

The draft NO2 prosposal document suggests the government may get tough on red diesel use (and misuse). It states: “The government has launched a call for evidence on the use of red diesel in order to improve understanding of eligible industries and current use, particularly in urban areas.”