Electric Avenue - driving from Edinburgh to London in a Tesla Model S

Saddle up, knights, your charger is here

THE ROUTE from Edinburgh to London has become a benchmark for electric cars since 2011, when the BBC took four days to get there in a prototype battery-powered Mini, stopping eight times to recharge. Tesla, which was then selling its Roadster, sent its two-seat convertible to cover the same route and completed it in 18 hours.

By the beginning of this year, a faster charging network had been developed, allowing a Nissan Leaf to go from London to Edinburgh in 13 hours, having to charge eight times.

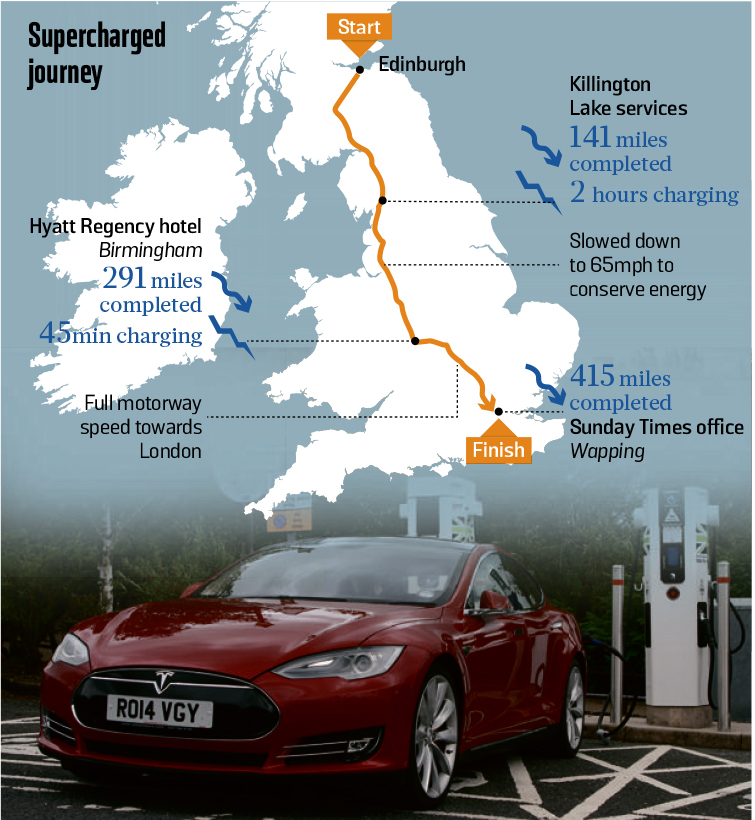

And last week, The Sunday Times notched up another first: travelling from Edinburgh to London in 12½ hours, recharging just twice, using Tesla’s superchargers which, for the first time, make long-distance travel by electric car a realistic prospect.

The aim was not to set a speed record — indeed, we took the trip at a leisurely pace, stopping to keep a photographic and video record — but to see whether the superchargers really could achieve Tesla’s aim of making long-distance driving in an electric car as fast and easy as in a conventional car.

Tesla claims its chargers — for use only with its own cars — will provide the vehicle with enough electricity for an additional 130 miles of motoring in 15-20 minutes: long enough for a short rest and a coffee before another two-hour drive.

The first of two supercharging stations in London opened in June and a third was switched on in Birmingham last week, taking the first steps towards what Tesla says will be a network stretching most of the length of Britain by the end of the year.

But does it work? We left the grey and miserable clouds over Edinburgh to find out. We were at the wheel of a Model S Performance Plus executive car, which, when fully charged, displays a range of 265 miles.

Our sat nav showed The Sunday Times’s offices in central London were just over 400 miles away — easily achievable travelling non-stop in a conventional car on a tankful of diesel. However, stopping to recharge doesn’t have to mean a slower journey. Most people stop en route for loo breaks, coffee or meals, so plugging in doesn’t necessarily cause extra delays. In fact, the Department for Transport recommends drivers on long journeys stop every two hours for at least 15 minutes.

Until now, electric cars have been marketed at urban commuters, who typically travel short distances at low speed and therefore place few demands on the batteries.

Some companies are even unwilling for their cars to be tested over long distances: last year, a test of one, arranged by The Sunday Times, was cancelled when the manufacturer learnt we planned to take it on a 300-mile trip from Sunderland to London.

As the Tesla swept through the Scottish hills, it felt built for the task. The Model S Performance Plus has an 85kW battery and will reach 60mph from standstill as quickly as a Porsche 911 Carrera S. A surge of electric power propels the car forwards in silence, while the huge dashboard touchscreen is intuitive to use, like an iPad.

The £68,700 car’s official range from a full battery to empty is 312 miles, but Tesla says most buyers will average about 265 miles. A mid-range model, costing from £57,300, offers less power and reduced performance. Both models include unlimited access to the supercharger network for the car’s lifetime, as well as an eight-year, unlimited mileage warranty for the battery. Owners of the third car in the range, with a 60kW battery, pay £50,000 for their vehicle but supercharger access costs a one-off £1,800 fee.

After 141 miles of driving, the range shown on the dashboard of our car had dropped from an almost fully charged 245 miles to 31 — sooner than anticipated — and we pulled into the Killington Lake services, near Kendal in Cumbria, to replenish the battery. Tesla’s charging stations do not yet extend this far north, so owners need to use chargers designed for smaller and less powerful electric cars.

The Ecotricity outlet we used needs just 30 minutes to provide half a charge to cars such as the Nissan Leaf or BMW i3, but because the Model S’s battery is so big, it took four times that to restore it to 80% capacity, giving us a range of 211 miles, according to the dashboard.

Two hours is a long time at a service station. There’s only so long you can spend thumbing through car magazines and drinking coffee until the novelty of free electric power (as long you belong to one of several charging schemes around the country) wears off and you start feeling trapped between WH Smith and the gambling machines.

Back on the road, the charge meter, calibrated in miles of travel left, was again dropping faster than the actual miles, even when we set the cruise control to 65mph to save energy. One possible explanation is that the car is built in California, where speed limits of 55mph are common. At the legal limit on a British motorway wind resistance is higher and pushing the car through the air saps energy faster. Having set off with a large safety margin (60 miles more than we needed), we ended with just 18 miles in hand. A single diversion or missed junction could have ended the trip.

Tesla says that the range indicator is not based on Californian conditions but on a typical driving style. “With any car, as speed increases, the range can drop, just as if the speed decreases there is the potential for higher range to be achieved,” said a spokeswoman.

The simplicity and effectiveness of the Tesla supercharger outside the Birmingham Hyatt Regency hotel showed how the system should work. Plugging in takes seconds and charging is so fast you can watch the number of miles of range increasing, like the digits going round on a petrol pump in slow motion.

About 20 minutes later there was enough range to make it the 120 miles back to London but, armed with the knowledge of the previous leg, we elected to wait a further 25 minutes until we had an indicated 250 miles before setting off. We arrived at the Sunday Times offices, close to the City, having covered 415 miles with 85 miles of charge left, according to the dashboard.

So is the era of the electric car finally here? For the first time, long-distance driving is feasible — once you learn how fast the car uses electricity and can push “range anxiety” to the back of your mind.

Tesla owners will need to factor in 20-minute charging breaks every two hours on long journeys. The regime is at least tempered by the knowledge that they won’t have to pay extra for the electricity.

The company has plans for at least a further 10 supercharger locations in Britain, allowing drivers to travel the motorway network, and, by the end of the year, to reach Paris and then Geneva. Barcelona and the south of France will be next.

Elon Musk, Tesla’s owner — who co-founded PayPal, won a contract with Nasa to supply the International Space Station and successfully established his electric car company during one of the worst recessions in memory — would no doubt have hoped charging points could have been set up more quickly in Britain. A dispute with Ecotricity, which has its rapid chargers at most motorway services, seems to have delayed the installation and — at the moment — there are no Tesla fast chargers on the motorways. Chargers in city-centre hotel car parks are likely to prove inconvenient for many.

So how does the future look for the electric car? Penalties announced recently for diesel drivers show that the squeeze on fossil fuels is tightening. Each time further penalties are slapped on emissions, the case for electric cars looks stronger. In California, the tax structure means that buyers of conventional cars are subsidising every Model S produced at the Fremont plant.

In Britain, taxpayers subsidise the purchase of each electric car by up to £5,000. Such subsidies have provoked a backlash in America and may do so here. The Taxpayers’ Alliance has said that those who can afford a £50,000-plus car should not need financial assistance from hard-pressed taxpayers.

But these concerns are likely to be overtaken by the pace of technology. There has been rapid improvement in the performance of lithium-ion batteries, which power the Model S. Musk is promising a new model, unofficially called the Model E, which could arrive by the end of next year and is expected to sell for around £30,000, the critical price point for mass-market take-up. If it can match or exceed the Model S in range, and if the superchargers are installed as fast as Tesla hopes, then even without a government subsidy it will rival petrol and diesel cars from the likes of BMW and Audi.

Until then, and until a sufficient number of Tesla’s fast chargers are in place, the Model S remains a car for early adopters. Remember, though, that is what they said about smartphones — right up to the launch of the iPhone in 2007. And look at what happened after that.

The electric best, for less

BMW i3 Range Extender, £28,830*

Best for hip young families who want a range-extended electric urban runaround that can venture beyond city limits. A two-cylinder petrol engine recharges the batteries. The doors open like those of a saloon bar to give good access to the rear seats.

Max range 160 miles

Renault Zoe, £13,995*

Best for drivers who don’t travel long distances, as the range is no more than 60 miles in cold weather, or 90 when warm. It’s affordable, compact for town driving and parking and relatively good fun, while the interior is simple to use yet does a nice line in geek chic.

Max range 90 miles

Vauxhall Ampera, £28,750*

Best for those who need a large, comfortable EV but can’t afford a Tesla. The Ampera is a range-extended electric car, which offers an electric range of 50 miles and has a petrol engine that acts as a generator.

Max range 360 miles

* After allowing for government grant

Don’t want to go all electric? Here’s our buying guide for the top ten most fuel efficient hybrids