Fallout from hard Brexit could drive up cost of cars by £2,300

As a share of GDP, 12% of Britain's exports go to EU while a little more than 3% of the EU’s exports are destined for our shores

MORE THAN £2,300 could be added to the price of an average car under a “hard Brexit”, according to research.

A study found that the cost of a new car was likely to rise by as much as 10% because of the imposition of tariffs on cross-border trade between Britain and the European Union.

The research, by PA Consulting, said that almost six in ten cars driven on British roads were imported directly from EU member states, with manufacturers likely to pass on any tax rise directly to customers.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

The report also warned that the cost of exporting British-built cars to the EU, estimated at £460m for each carmaker, would render plants unaffordable and force most companies to consider relocating factories to the European mainland.

One of Britain’s most senior shipping bosses also warned yesterday that “massive delays” were looming at Channel borders because of a failure by France and Belgium to draw up post-Brexit customs arrangements.

The conclusions were made after it was announced that Theresa May would trigger Article 50, the formal process for leaving the EU, on Wednesday, March 29. A letter officially notifying the European Council of Britain’s intention to quit will set in train a two-year process that is expected to lead to the UK leaving the union at the end of March 2019.

The prime minister has indicated that the UK cannot remain within the single market, with free movement of people — a precondition of membership — seen as too high a price to pay.

It seems certain that a clean break from the EU, a so-called hard Brexit, will be the likely outcome. A new trade deal would then be negotiated, taking up to ten years to finalise. In the short term, Britain probably would be required to follow World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules on tariffs.

The scale of tariffs may also dent the ability of European carmakers to keep British plants open

The report from PA Consulting said that this would be the “worst-case scenario” for Britain’s automotive industry, which is worth almost £72bn and supports about 800,000 jobs.

WTO tariffs would add 10% to the cost of finished cars, with 4.5% added to the value of components added to vehicles, including engine parts, wheels and bodywork.

Average UK-built cars exported to the EU are valued at £20,900, the report said, with each one carrying £6,270-worth of parts originally imported from the Continent. This would suggest that “the potential cost increase under WTO arrangements could be as much as £2,372 per car”, PA Consulting said.

It added: “Equally, European-based manufacturing companies would face similar costs for exporting to the UK from mainland Europe. Increased time delays at borders could also impact ‘just-in-time’ supply chains that are currently standard for the industry.”

Last year, the EU exported more than £30bn-worth of cars to the UK, accounting for 57.5% of all those sold in Britain.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

The scale of tariffs may also dent the ability of European carmakers to keep British plants open, the report said. This month, Peugeot’s French parent company completed a takeover of Vauxhall, raising doubts over the company’s UK-based operations in Ellesmere Port and Luton. PSA Group insisted that it was “not talking about shutting down plants”, but the PA Consulting report said that under WTO rules companies “may look to relocate their manufacturing back to the EU”.

The conclusions were made as Britain’s shipping industry warned that France and Belgium had shown no sign of addressing the threat of a “hard” border. Guy Platten, chief executive of the UK Chamber of Shipping, warned that there were going to be delays at ports.

“Our feeling is that other countries in Europe are not in any way prepared,” he said.

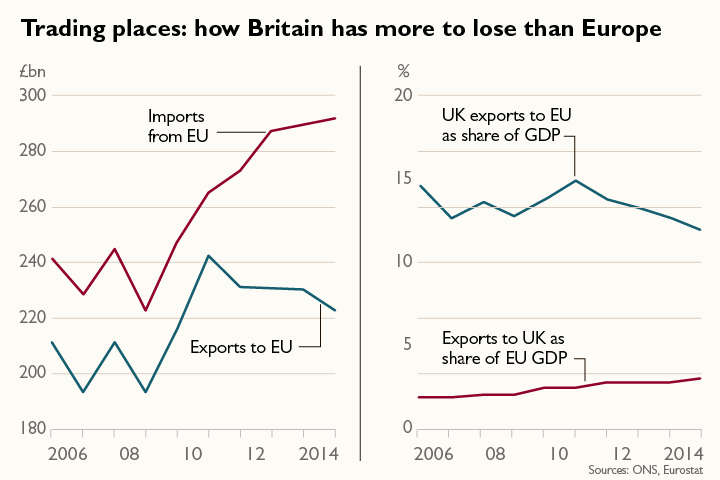

Here are two graphs that tell contradictory stories. The first appears to back the case that Europe will be in no position to play hardball because it sells more to us than we do to it.

The problem, as the second graph shows, is that it takes no account of the size of our respective economies.

So while 12% of Britain’s exported goods, as a share of GDP, are destined for the EU, a little more than 3% of the EU’s exports, as a share of its GDP, are destined for our shores.

Graeme Paton, Transport Correspondent and Oliver Wright, Policy Editor

This article first appeared in The Times