The interview: Camilla Long meets Clarkson, Hammond and May

It’s like the most fabulous male midlife crisis ever

IN 2007, James May seriously considered killing Jeremy Clarkson. It was a long shoot, cold temperatures. The three of them were “on our trip to the North Pole”, says May, when suddenly, he found himself alone with Clarkson.

“We were miles away from the crew behind a big sort of ice floe thing,” he says, “so nobody could see us. And I had a shovel …” He pauses. “And I thought, YEAH!” He could have staved his head in or just smashed him silently into the sea. He could have pushed him over, or cut him off completely. He thought: “This bit’s going to melt,” by which time Clarkson, bleeding and unconscious, would have simply floated away and been “gone” for ever. It wouldn’t be a loss, no. “We never liked each other in the first place,” he grins.

Clarkson agrees that May became inexplicably “murderous” during the icy trip. The explorer Ranulph Fiennes had warned him that the “weak and feeble-minded will not be able to cope”. Even Fiennes, who is Clarkson’s idea of the perfect human being,

said he’d become “murderous” himself, so it was no surprise that May wanted to bash Clarkson’s head in. According to Clarkson, this is because May is “stupid”, sleepy and slow. Because obviously no one would ever really want to kill Clarkson. Would they?

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

We are sitting in the darkened back room of a pub, five minutes from the new offices the trio share in Chiswick, west London. Clarkson sits in the middle, a tall, loping man with ungovernable limbs. May is a soft, sloping sort who looks like an off-duty instructor of the lute. Hammond is quiet, big-eyed. All of them seem hushed, focused, “scared”. It has obviously been the most stressful year of their lives.

Losing everything and having to build their show back up from scratch has been “daunting”. After Clarkson was dumped from Top Gear last year, they went from being the biggest television stars in the world to being the owners of a single, resentful bog brush. Moving into temporary offices on “day one”, booms Clarkson, they found they did not have a pot to piss in. Not a desk, a chair, nor even a printer. There was a space “about half the size of this bit of the room”, he says, motioning into the dark. But otherwise “we had to buy bog roll”, he booms. “BOG ROLL! We actually bought a BOG BRUSH.”

“And a mop,” says May.

“And a mop,” nods Clarkson.

“And a bucket,” says May.

I think at that point they probably did slightly wish May had killed Clarkson. As the presenters of Top Gear they had been watched by 350m people. The show is dubbed into eight languages, including Farsi, where one of Clarkson’s favourite phrases, “gentleman’s sausage”, was translated as “Pharaoh’s dried testicles”.

It was lusty, banterish, bombastic — and, in some people’s opinion, bloody awful, terrible and politically incorrect. But after a series of dramas, including a “fracas” in which Clarkson allegedly punched a producer and called him a “lazy Irish c***”, most people were both startled and sorry it was over. Indeed, 1m people petitioned the BBC to take them back.

BACK IN THE FAST LANE From left: Richard Hammond, Jeremy Clarkson, Camilla Long and James May

Clarkson is not openly bitter, but I’m fairly certain his life’s task is now to create a new show so brilliant it will totally destroy the BBC. As ever, he approaches everything with the searing intensity of the final showdown in a Bond film. Even this interview feels as if it is some kind of duel to the death on the rim of a volcano. (Obviously, he is already in character by the time he turns up. He is a Bond villain, probably Blofeld, and I am his “vursy adwersary”.)

The pressure is undoubtedly on. Clarkson and his crew have landed a £160m deal with the online streaming service Amazon Prime to deliver a car show, called The Grand Tour, over three years. Each year they will produce 12 episodes. Each episode sees the entire circus travel to a new country, a bit like Formula One. From the clips I have seen, the new show looks like something more pantingly explosive than every single Michael Bay film rolled together. Admittedly, it is in the spirit of Top Gear, but, as Clarkson would say, with much bigger tits. There are machineguns, fighter jets, terrorist-level detonations, cars dangled at 1, 000ft, not to mention Clarkson slamming tanks across the usual protected rainforest/untouched salt flats/virgin savanna. It looks like the most fabulous midlife crisis ever.

“The BBC is a 1920s operation that is going to have to face up to the modern age”

Jeremy Clarkson

For the past few months, the trio have been busting the enormous budget, pinballing from Venice to Los Angeles to South Africa, where one of the make-up

girls was so horrified about how their “greying” skin might look in the new ultra-high-definition 4K format it is shot in that she decided to “entomb” their heads in “three-quarters of a tub” of orange foundation. When they walked into the studio, their heads were “simple orbs”, says Clarkson, massive “pumpkins”, hidden in a thick rind of Hollywood make-up.

I find it difficult to look at Clarkson on normal television, so I cannot imagine what it will be like when every pore is exaggerated to cinema quality.

It is an experience to lay eyes on him — especially if, like today, he has decided to … well, let’s say dress down. He wears the crumpy jeans and the leather jacket, as well as a paper-thin patterned shirt I’ll be damned if he hasn’t either heavily vomited on or woken up in five days on the trot. His hands are huge, his face is huge and craggy. When AA Gill took him to the gay paradise that is Mykonos, he said that terrified boys physically shrank into walls as Jeremy “the taste apocalypse” passed by.

May agrees there have indeed been “some quite unkind comments saying haven’t they got old, don’t they look ancient. Yes, that’s true, we are getting old. I’m going grey, he’s …” he points to Clarkson, “very fat”, and “he’s …” he points to Hammond’s ratty new goatee, “got a beard. But we’ve been honest about everything else: why shouldn’t people watch us get old?”

Clarkson is proud they don’t have a wardrobe budget and “we pay no attention to how we look”. Even Hammond doesn’t seem to have actually dyed his beard. I’m more worried about the soul-charring new stunts than their mascara, though. I’m not sure how they will keep it all up now they are collectively 155 years of age. After all, one of the new scenes in the show cost “not far off” £2.5m, a “Mad Max-style” extravaganza complete with monster vehicles, acrobats and 2,000 extras. Andy Wilman, the producer of the show, says he cannot wait to see if Clarkson, 56, can get in and out of a low-slung car “in three years’ time” without leaving “a big puddle of piss in the seat”.

“Three years’ time? Three weeks’ time,” mutters May.

Clarkson says he “gets out of breath doing the simplest things”. At one point he was frightened he might drop dead in Namibia: “I was genuinely scared.

I thought what if [the car] does break, what if I have to walk through the desert? I won’t be able to. I can’t even walk over there. I can’t even come and shake hands goodbye.”

But it was May who nearly died in Venice. He was swimming to a jetty “and I thought I would drown. I couldn’t get out of the slippery thing. I had completely run out of strength.”

Halfway through filming, he also broke his arm. He was so drunk during the second shoot for the new show that he slipped and fell over when he came out of a pub. Everybody else “managed to get into their cars”, says Clarkson, “but somehow James slipped”.

“He took a tumble,” coos Hammond.

“He took a tumble,” coos Clarkson.

May says he had “graciously” offered to be collected by his partner, leaving the others to be chauffeured. He fell over on his way to the car. He thought he’d be fine walking on the slippery pavement, seeing as “if you’ve had a few, legend always has it that you can fall over as much as you like, fall off a wall and bounce. But it turns out not to be true. If you’re shitfaced and fall over, you still break your arm.”

Man laughter.

“Still,” says Clarkson, “it did give us some good material, which is all that really matters.”

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

Clarkson will do anything to land “good material”. If May hits his head on a rock and is rushed to hospital, as he did when they were filming in Syria, “that was like, just take a moment, oh, he’s all right. Straight to laughter.” If Hammond crashes at 288mph and spends two weeks in a coma, as he did in 2006, when he wakes up, “straight to laughter”, he says.

Part of the attraction of Top Gear was what Clarkson calls “healthy banter” and what May calls “persiflage”. Strip away the cars, the celebs, and Top Gear, sorry, The Grand Tour, is three men chuntering away about sexy Ukrainian bodywork and “cock”. It is exactly the sort of conversation you’d hear on any day, in any year, in any town outside the M25, and it is voraciously, hilariously popular. It is the language of tyres, tits, moobs and sweat. Sometimes I think that Clarkson is more akin to a whole political party than the presenter of a telly show. Personally, I love telling people that I love him — they always seem so shocked.

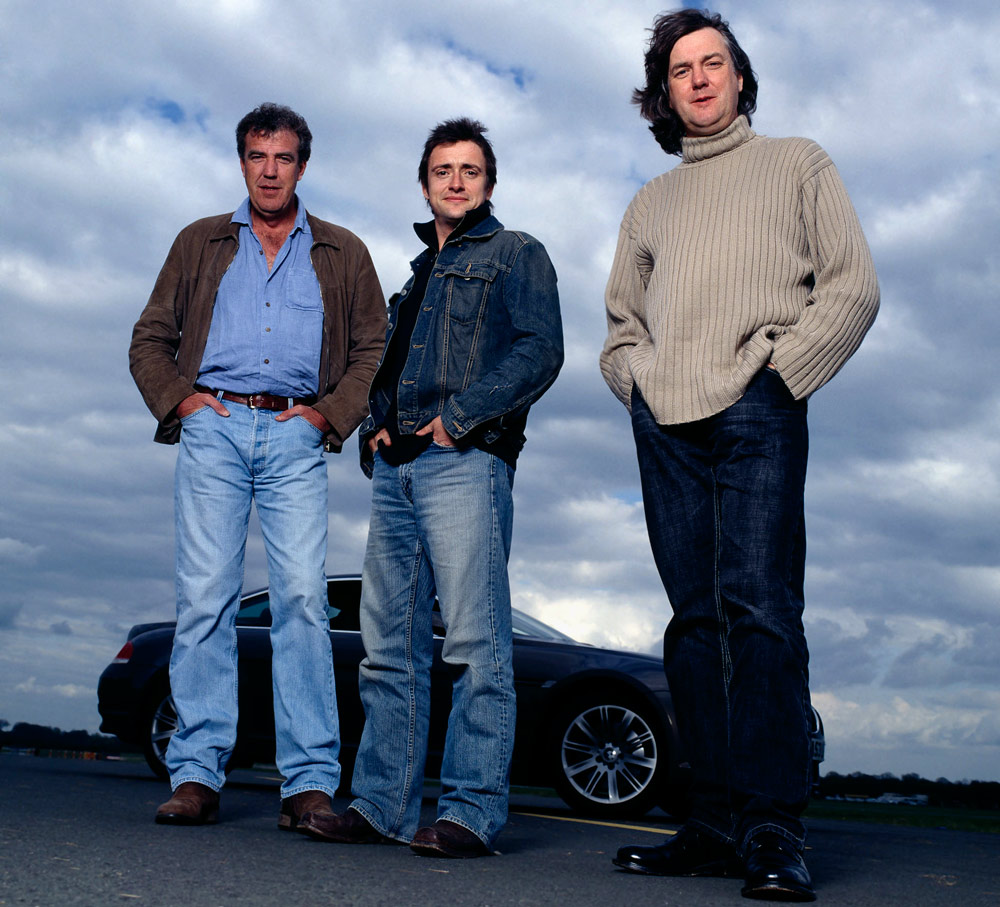

WINNING FORMULA The Top Gear trio in 2004, a year after May (right) joined to complete the classic line-up

Having said that, being on screen with him can be a shock. I once made the stupid mistake of teasing him during a recording of Have I Got News for You. In response to Clarkson’s statement that “kar means cock in Albanian”, I said: “I think you’ll find car means cock in English as well.” Whereupon a terrible chill descended and he attacked me for not knowing what diesel was. His banter isn’t “bullying”, he says now, because “we can’t bully each other, we’re all on a plateau” (he means a level playing field). But sometimes it can feel a bit like being run over by a tank.

How does this go down with Amazon? So far, the Americans haven’t really engaged. Clarkson has not even met the boss, Jeff Bezos. “Amazon are very happy for us to say whatever we want,” he says. He will continue to attack everyone, even Americans, whom

he has called “fat, stupid and rude”. Clarkson says he is their editorial policy decision-maker now — obviously I cannot wait to see what this means in real terms (he once called Sarah Jessica Parker “a boiled horse”). At the BBC he had a whole person whose job it was just to stop him saying anything unacceptable, and look how that ended.

We can probably date the decline of Top Gear from mid-2013, when an executive named Danny Cohen was promoted to BBC director of television. It wasn’t just that Clarkson hated him. It was more he felt betrayed by him. For 25 years he’d been the BBC’s golden toddler. Suddenly here was someone who not only didn’t like him, but didn’t even get what he did.

“Danny and I were famously not ever going to get on,” Clarkson says. Shortly after Cohen arrived, he started to “wind him up”. He’d deliberately write things he knew would infuriate the new director. “I mean, I would think, ‘I’m going to say this. Nobody else would care less. But Danny Cohen, his teeth will move about with rage.’ ” He did it “because I know what his views are on everything, and I just thought, it’s so easy. ’Cos those views are not echoed by anyone living in the country that I know about.”

Also, there is the slight added problem that Clarkson loves “telling people lies”. “Sometimes the truth can be quite boring, so it’s much funnier to make a story up.”

Almost immediately, things started to go wrong. First there was the scandal of the “slope” on a bridge over the River Kwai in the Burma special (slope is a derogatory term for Asians). Wilman apologised. Then there was the scandal of the n-word, an outtake mysteriously leaked in which Clarkson claimed he desperately tried not to say the word but failed. Clarkson apologised (sort of).

Then there was Argentina, in which Clarkson didn’t notice the number plate of the grey Porsche he was driving, H982 FKL, was offensive to Argentinians. May claims that any suggestion they rigged the plate is “total horse’s arse”. Clarkson says: “It couldn’t possibly have happened … Swear on the children’s eyes.” But looking at footage of the team as their poor camera crew were stoned out of the country, I can’t quite tell whether they were thrilled — or really thrilled. Also, the police inconveniently discovered a set of interchangeable number plates in the Porsche’s boot — one of them being BEII END (“bell end”). So by the time it came to the inquiry, “nobody believed us”, says Clarkson.

About five months later, the end came when Clarkson reportedly punched the Top Gear producer Oisin Tymon in the reception of a country-house hotel, when he arrived knackered after 10pm and discovered there was no steak. I had thought Clarkson might be a sort of half-hearted “handbags at dawn”, girl on girl, mano a mano type of a fighter, but according to the BBC he harangued Tymon for a whole 20 minutes, only stopping when he was dragged off. (Wilman later pointed out it is almost impossible to berate someone nonstop for 20 minutes: “Try it with a stopwatch at home — you can’t.”)

At first everyone tried to brush it off as a “fracas”, but it was clear this time Clarkson had gone too far. He was dropped from Top Gear and later paid the producer about £100,000 in a private settlement. At the time, he said: “I went home thinking, ‘This is a bit ugly.’ ”

I know Clarkson won’t say anything about it now (“lawyers”), so I ask Hammond and May if they ever felt annoyed he let them down.

“Lawyers,” says May, hesitantly.

“Just can’t,” says Hammond, more hesitantly.

“Seriously,” says May. “Lawyers.”

“The evidence is,” says Hammond, after a small pause, “here we all are, talking to you. Our actions speak louder.”

I’ll take that as a no.

Cohen left the BBC just a few months after Clarkson’s contract wasn’t renewed. “Of course he’s gone,” snaps Jeremy. “That was inevitable. You can’t have a man like that running anything.” And while he thinks the BBC is “fantastic”, he thinks it can no longer handle talent or big shows.

It is a “1920s” operation that is “going to have to face up to the cruel realities of the modern age”, he says, adding that scheduling is also “an issue”. “It is a 1920s operation trying to operate in the 2020s, which is tricky. But of course it will survive. Of course it will.”

FRIENDS REUNITED Filming The Grand Tour in Portugal, with a hybrid supercar face-off between a McLaren P1, a Porsche 918 Spyder and a LaFerrari

May quietly misses the BBC. “I miss the warm feeling I get from being part of [respectability and the establishment],” he says. He thinks of it as “a sort of third parent”. But after something bad has happened, “you just have to walk away from it with dignity and not be bitter about it”.

Clarkson reluctantly admits to watching two episodes of the revamped show: “It was a television programme about cars,” he says blankly. He says it is not for him to pass judgment “on the efforts of others” (not a comment I can take seriously from a man who called Gordon Brown “a one-eyed Scottish idiot”, before refusing to apologise for “idiot”). But he can’t have been too crestfallen when new hosts Matt LeBlanc and Chris Evans crashed.

So what went wrong? Evans (since departed) was probably too nerdy. Part of Clarkson’s genius is that he has no time for overweeningly earnest reviews or sentimentality over car parts. He says, rather dismissively, that it is the other two who “collect” cars; he drives just one car, a Golf GTI. He just wants to drive fast, humiliate celebs, blow up some heart-breaking nook of the landscape and have fun. Ranulph Fiennes is his favourite person precisely because he “has no time for weeping” and “sawed his own fingers off”.

By this stage of the interview, I am only just getting the hang of the trio’s dynamics. Clarkson is “loud and badly behaved”; Hammond is the straight one; May is the pantomime dame (“Widow Twankey”), with a touch of the batty, hapless, flowery academic. He is a former flautist and choirboy who read music at college. Later, Clarkson will mouth that May’s partner is a “dance critic”, as if this is the weirdest

thing ever.

When I tell Clarkson I find Hammond so earnest it is nearly impossible for me to take in anything he says — even when he talks about dying — Clarkson leaps to his defence, saying, “He’s not as boring as we make out. He’s very funny.”

“I was genuinely scared. What if the car breaks and I have to walk through the desert?”

Jeremy Clarkson

Clarkson, however, is the real enigma. On the one hand he is very hard-working, a defiant beacon of masculinity (“I just cannot do what I’m told. I love getting into trouble”). But on the other he is also strangely soft and girly. He drinks organic rosé and loves tabloid gossip. He is kind to his friends, likes to get wasted with women, and loves boyfriend chat. At one point, we get entirely lost discussing Simon Cowell’s “gentleman’s sausage”. At which point I pounce. So what was the body count on set — any altercations?

“That was a fairly blunt attempt,” says Hammond.

Well, have either of you ever wanted to punch Jeremy?

“I did kick him once,” says May.

“I know what you want,” says Clarkson. “And you’re not going to get it. You can sit and ask. You can think, well, we’ll sit here and he may come out with it. Your phone battery will go flat and you won’t get anywhere with it.”

But I only asked if May had punched him.

“You CAN’T,” says Clarkson. “I’m not even … I can’t even legally go there.” He gives an enormous sigh. “Try as much as you like. We’d have to go to prison.”

As it is, Clarkson has been arrested twice: “Once in France, mildly drunk, once in Greece, mildly drunk.”

In Greece, he only escaped when he was told to get out of the policeman’s car: he ran away, still handcuffed.

I have no idea if this is 100% true or not, but the somewhat tiddly bit sounds fairly authentic. If any of them actually has an issue with booze, no one’s admitting it. May insists: “We do not have a drink problem. He simply likes rosé, I like beer and wine, Hammond likes gin and tonic. We don’t do it to excess. We drink to content, not capacity.”

But as we trickle out into the yard after the interview, we manage to disappear five bottles. Off-duty Clarkson is different. He is less coiled, more relaxed, vulnerable, a bit self-absorbed. He fears tabloid fuss, but seems disappointed if he isn’t mobbed or papped.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

I have no doubt he can be a control freak on set: he is a technical obsessive, a details man, someone who really bothers. At one point he starts foghorning at one of the techies who has arrived with a video camera, telling him how to do his job.

Sometimes he has to actively remind himself that some people aren’t as fortunate as he is. He does this by remembering the terrible pity he once felt for a man working in a branch of PC World in Liverpool. He found himself staring at the shop through the rain “and I thought, if he works really hard for a few years, he could become a store manager. If he works really, really hard for 10 or 15 years, he’ll become perhaps zone manager. Then he’ll be able to go to a country-house hotel once a year and have a business discussion, maybe with his secretary. And that will be the highlight of his life … And we’re whingeing because we’ve been in a bloody helicopter? So it does have a profound effect. I do think about that a lot.”

He pauses. “I don’t work in PC World …” Don’t we know it.

The Grand Tour presenter CVs

JEREMY CLARKSON

Age 56

Training Former Rotherham Advertiser journalist

Favourite car Lexus LFA

Favourite saying “On that bombshell”

RICHARD HAMMOND

Age 46

Training Former Radio Cumbria presenter

Favourite car Porsche 911 GT3 RS

Favourite saying “That’s torn it” (milliseconds before crashing a jet car at 288mph)

JAMES MAY

Age 53

Training Sacked Autocar features editor

Favourite car Ferrari 458 Speciale

Favourite saying “Oh cock”

Contents

Click the title to view the page

- The interview: Clarkson, Hammond and May

- Back from rock bottom: exec producer Andy Wilman on fighting back

- Jeremy Clarkson: the best idea for a new show… in the world

- Richard Hammond: better than camping in the Arctic

- James May: entering the 4K revolution

- The amazing travelling circus: this is no ordinary tent

- The cars of The Grand Tour, season one: 12 star cars

- The grand gallery: behind-the-scenes photos

- Quiz: How much do you know about the terrible trio?

The Grand Tour begins on Amazon Prime on November 18, 2016. Click here to sign up and watch.