Hyundai: Plug-in electric cars are ‘quick fix’ but hydrogen must be part of future

'Ditch the tribalism and go for mosaic of propulsion solutions'

AROUND a decade ago, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles were considered by most to be the panacea for our dirty road networks: zero emissions at the tailpipe (other than water), tanks capable of powering a car for hundreds of miles and refuelling that takes about the same time as filling with petrol or diesel.

And then Elon Musk happened. The Tesla founder proved that plug-in, battery-powered electric cars could be fast, long range (the latest Model S saloon is rated at up to 375 miles per charge), fun to drive and genuinely desirable.

Yes, they take longer to refuel (although charging times are coming down), but their major advantage over fuel cell vehicles is that they can be topped up anywhere there is an electrical outlet, whereas a hydrogen tank can only be filled at specialist refuelling stations.

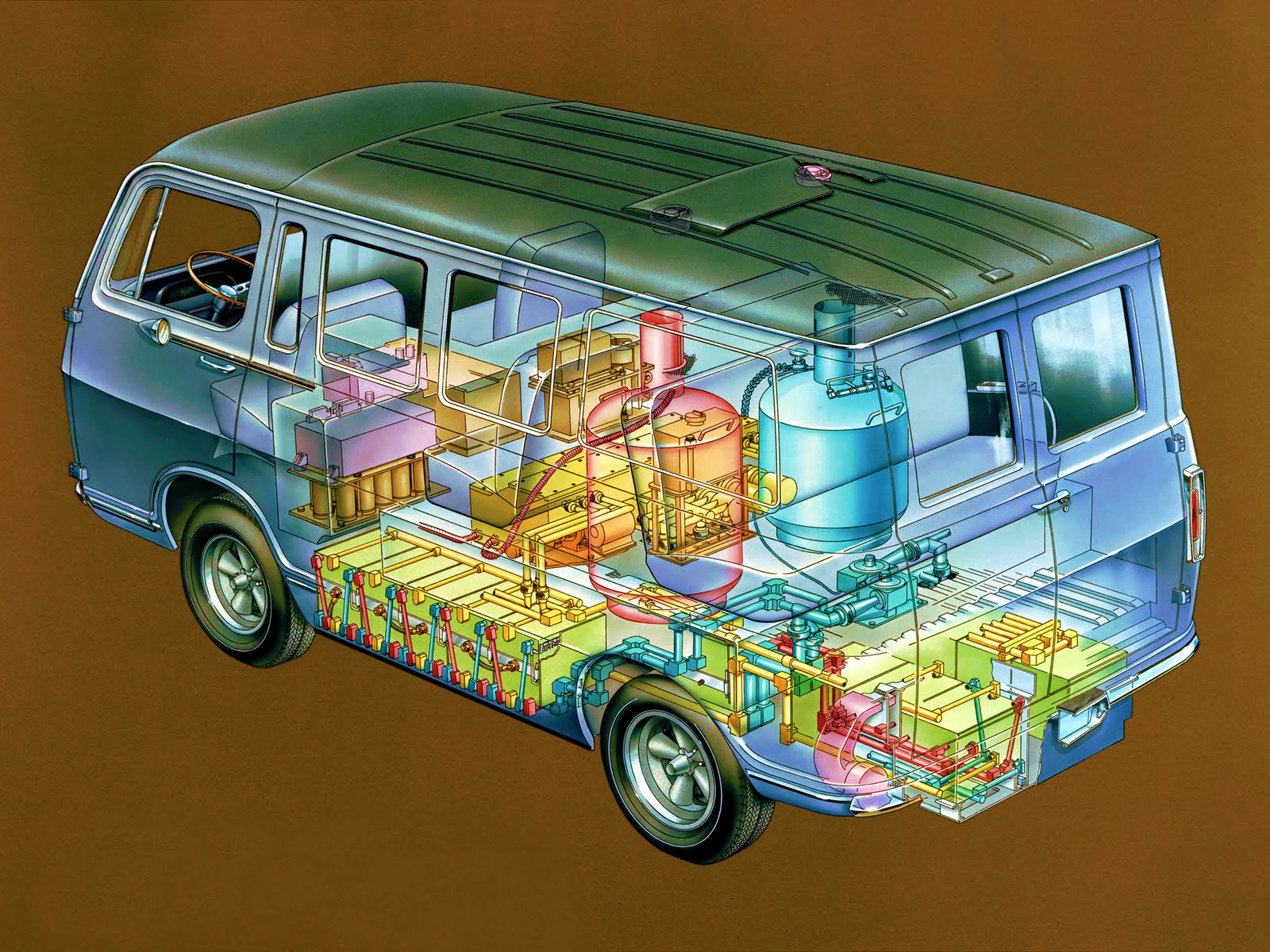

Since the 1960s, when General Motors introduced its first fuel cell vehicle concept, mass-market hydrogen cars have always been “about ten years away”, yet more than 50 years later there are just 10 hydrogen refuelling stations in the UK, whereas virtually every building in the country has an electrical hook-up.

This has led Musk to speculate that hydrogen tech is no more than a way for car companies to keep the green lobby off their backs while they get on with building petrol and diesel cars.

Yet recent developments in hydrogen fuel cell technology, including the introduction of the first production cars from Honda, Toyota and Hyundai, has reignited the debate, with those inclined to speculate on the future of road transport splitting into one of two groups: hydrogen heads or plug pushers.

For Sunday Times columnist Jeremy Clarkson, hydrogen has been the only real solution. “I’m baffled by the car industry’s apparent reluctance to think more seriously about hydrogen as a replacement for petrol and diesel,” he wrote in 2016.

“Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, so we wouldn’t run out of it for about a billion years, and it’s clean too. A car powered by hydrogen fuel cells produces nothing from its tailpipe but water.”

Musk, on the other hand, went as far as to say using fuel cells in cars was “extremely silly” and “dumb”, pointing out that you need to create hydrogen gas by splitting hydrogen atoms from another source, such as water, then compress and store the gas. This process takes energy, and Musk said doing so is “about half the efficiency” of simply storing solar-generated electricity in a battery.

Some car makers, too, have picked sides (or simply watched the debate from the sidelines). Honda was a very early proponent of fuel cell vehicles but rival Toyota became the first car maker to bring an “ownable” model to market, with the Mirai, in 2018. Neither company has been quick to embrace pure-electric plug-in technology.

Until recently, Hyundai was very much in the hydrogen camp, too, but Tesla’s success has shaken up the industry and the Korean car maker was quick to adapt. It now has a number of pure-electric, hybrid and plug-in hybrid models on the market, alongside petrol and diesel counterparts.

Its most impressive plug-in car to date is the Kona Electric, which costs from just under £32,000 and has a range over up to 279 miles per charge. It’s the sister car to the equally impressive Kia e-Niro, and at the moment both Korean car makers seem to have the same problem — too many people want to buy one. Waiting lists for Kona Electric and e-Niro in the UK are currently 12 months long, with major delays in battery supply at the Korean manufacturing plant.

It’s a nice problem for a car maker to have, in many ways, and it proves there is a market for affordable, long-range plug-in cars from brands other than Tesla, but the risk is that customers drop out of the queue and find an extra £5,000 or so for an entry-level Tesla Model 3 instead. The companies are ramping up production as fast as possible to meet demand.

“Battery electric is fantastic; perfectly suitable for cities and short journeys”

But the apparent success of Hyundai’s plug-in cars doesn’t mean it is ditching hydrogen technology — far from it. At the end of last year the company announced “FCEV Vision 2030″, a roadmap for the next 10 years, with a coporate investment of KRW 7.6 trillion (more than £5bn) and the aim of producing 700,000 fuel-cell systems annually by 2030, including 500,000 fuel cells for new vehicles (FCEVs).

“We honestly don’t know what the future will hold,” Hyundai’s Sylvie Childs told us at a driving event organised by the company last month. “We think that there will be a mosaic — different people will need different technology.”

Childs really believes in hydrogen, as one might expect given that she is the product manager for the new Hyundai Nexo fuel cell vehicle. She was at pains to point out that Hyundai has been developing fuel cell technology for 20 years.

But she’s not blind to the fact that plug-in cars have gained the momentum recently; even if it was a bit of a surprise.

“You know, five years ago we didn’t know we were going to have Kona Electric,” Childs said. “So that just shows that we have evolved and embracing the different technologies.”

Quite so — whereas the likes of Honda and Toyota appear to have been shuffling their feet when it comes to pure-electric cars, Hyundai has steamed into the space, developing battery cars alongside its hydrogen models — and bringing them to market. Judging by the popularity of the Kona Electric, hedging its bets appears to be paying off.

But pure-electric cars aren’t the sole solution, Childs insists.

“Battery electric is fantastic; perfectly suitable for cities and short journeys. There’s a long static time [while charging], but you can top up overnight, so that’s fine. It seems to be a quick fix as well, because electricity in terms of infrastructure is readily available. It’s good to try to electrify and reduce CO2 emissions [that way], particularly.

“So it is a good solution for now and the next 10-15 years for sure. [But] it’s not the only solution. I think you have to be realistic about that.”

Why?

“There’s a lot of transport needs that can’t stay idle. How do you run a fleet of buses when you have to wait 12 hours to recharge it? You need two buses when you could have just one diesel. It’s not viable, really. Hydrogen has really high energy density and so it can be the solution to replace diesel.”

Not putting all their eggs in one basket futureproofs car makers against the unknown, of course. So why isn’t everyone being so open-minded?

“I think there are companies who are backing one technology,” acknowledges Childs. “It is a big commitment for a company — it is a lot of investment.

“And also, you know, some people think it would be diluting the message.”

It’s a good point. A diluted message isn’t easy to sell — just look at how poorly the Labour and Conservative parties’ murky policies on Brexit have served them. The modern world demands clarity. On social media we’re encouraged to take sides in a with-us-or-against-us sort of tribalism. But the danger is that you end up backing the wrong horse, and in the case of choosing between hydrogen fuel cells and battery electric power, that can be a multi-billion pound mistake.

It’s not just car makers that need to invest in both types of fuel — governments also need to ensure the infrastructure is there to support zero emission transportation if they’re to meet current ambitious targets for CO2. The UK has a target of cutting CO2 emissions 80% by 2050, and its Road to Zero plan requires the end of sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2040.

For plug-in cars, that means an increase in public charging points. Currently there are 13,831 chargers at 8,642 locations serving 214,000 plug-in cars, but research suggests we will need 100,000 chargers when we hit 1m cars.

“Some people think backing both battery electric and hydrogen would be diluting the message”

For hydrogen cars, that means more hydrogen refuelling stations. More than the exisiting 10, certainly, and probably as many as there are petrol stations (8,394 at the end of 2018, according to Statista) if we really want a viable network.

“[Installer] ITM worked out that you need to have multiple stations in one area to make it work,” said Childs. “Two reasons: for the users, you have a backup, because when you have more users, they use the station more.”

In other words, you need to avoid queues forming at the pumps.

“Also, because they are used more, [having multiple stations is] more reliable.”

Translation: if one station fails, there’s another nearby.

“This is really what we’re trying to do in the UK. It would be nice to have a station dotted around the whole country, so it looks like you’ve got national coverage. But it is just one station in isolation. When it’s down, the cars can’t refuel, they get stuck. And the more it gets down, the less reliable the network becomes.”

Last year the government’s Office for Low Emission Vehicles (OLEV) announced the second stage of its £23m Hydrogen Transport Programme, with a proportion of £14m allocated to the funding of 10 new hydrogen filling stations. The previous phase saw £8.8m go towards four new refuelling stations and the upgrade of five exisiting stations.

“If we just keep sending the message out that the UK is all about putting electric car charging points in cities, then it’s difficult for Hyundai in Korea to send hydrogen cars over for us”

Childs says London is the main focus right now, partly because of the new Ultra Low Emission Zone, but also because “it’s a big population; its a big opportunity”.

Clearly this is an expensive endeavour compared with installing electric charging points, and state-backed efforts to date represent a drop in the ocean. The cost of the hydrogen to the consumer is also high: currently £12 per kilogram, with the Nexo’s 350-mile tank taking 6.4kg, so filling tank costs more than £75. That suggests a strong case for government subsidy of the fuel, if it is serious about the technology.

| Hyundai Nexo (hydrogen) | Tesla Model S Long Range (pure-electric) | Mercedes-Benz E 200 AMG Line Auto (petrol) | |

| Price | £65,995* | £81,650* | From £41,385 |

| 0-62mph | 9.5sec | 3.7sec | 7.7sec |

| Range (WLTP combined) | Up to 414 miles | Up to 375 miles | 366.3 miles¹ |

| Shortest time to refuel (approx) | 5min | 170 miles in 30min² | 5min |

| Cost per tank/ recharge | £76.80³ | £15.60⁴ / £24.00⁵ | £64.55⁶ |

| Number of UK public locations | 10⁷ | 8,385⁸ | 8,394⁹ |

“For me, it’s really important that people recognise that the government has made efforts,” says Childs. “Okay, it’s probably not a lot [so far] but there’s more. But there are companies in the UK that committing to hydrogen, not just us. It is happening and we’re building it step by step, but we have to stick with it.

“I’m hoping that it will ramp up next year because you can’t wait. We need to put the UK on the map globally and say we are serious about hydrogen. This is a bit of a vicious circle. If we just keep sending the message out that the UK is all about putting charging points in cities, then it’s difficult for us [Hyundai UK] to tell head office that we’re serious about hydrogen [in the UK], so give us some volumes of product.”

For car makers, the only sensible option right now is to hedge their bets. It’s expensive, yes, but not doing so could be even more costly: commercial obliteration. For the government, Hyundai’s approach suggests the same is true: unless we have a mix of solutions, and invest in a rapid roll-out, we may fall out of line with the rest of the world.

And for Musk and Clarkson, maybe it’s time to take a step back, acknowledge the pros and cons of both and admit, like Sylvie Childs, that “we honestly don’t know what the future will hold”.

* On the road price includes £3,500 government incentive

¹ Based on 33.3mpg combined fuel consumption and 50 litre fuel tank

² Maximum speed possible at a 150kW Tesla Supercharger. Most owners top up overnight at home.

³ Based on £12 per kg (including VAT) and the NEXO’s 6.4kg tank

⁴ Based on charging 100kWh battery at home from empty to full based on UK average 13p/kWh tariff, plus VAT (tariffs with cheaper off-peak charges are available)

⁵ Based on charging 100kWh battery at Tesla Supercharger from empty to full at 24p per kWh

⁶ Based on UK average price of unleaded on May 16, 2019, of 129.1p per litre

⁷ Source: Hyundai

⁸ Source: Zap-Map

⁹ Source: Statista

Britain’s clean fuel shame: how the UK has fallen out of the hydrogen car race

Hyundai NEXO hydrogen car includes filters to ‘clean up’ London’s air

https://www.driving.co.uk/news/10-electric-cars-248-miles-range-buy-instead-diesel-petrol/