Look, no hands: How close is the car of the future?

Why self-driving cars promises to be big business

WHAT IS the car of the future? When will it get here? How will we recognise it? In the 1960s, when the world was absorbed by space travel and putting man on the moon, the car of the future looked like something straight from the pages of the Eagle comic; a cross between a spacecraft, a fighter plane and a sports car. It never took off.

Today, the car of the future is commonly believed to be the self-driving, or autonomous, car. Vehicle manufacturers, the giant suppliers that they work with and media groups, including Google, are all moving towards a horizon where the driver has to do nothing more taxing than tell the car where they want to go.

It may not be what some drivers want to hear – especially those who enjoy driving or have concerns about the wider implications of privacy. After all, if the driver no longer has anything to do, it’s only a matter of time before their car becomes an extension of the office and living room rolled into one, with streaming movies, the supermarket shop and work video conferencing calls all carried out on the commute to work.

We take a peek into the future and consider what a driver’s typical day might be like in 2025.

The self-driving car

The year is 2025…

Before going to bed last night, you’d told your smartphone’s calendar to send tomorrow’s meeting address to your Volvo. While you have breakfast, your smartphone vibrates: it’s your car, telling you there’s low traffic on the route, which means leaving as planned to make the meeting on time.

That’s what you want to hear because the school run has to be fitted in beforehand. Walking up to the vehicle, it recognises your smartphone and today’s itinerary, adjusting the driving position and mirrors to your saved profile, and sliding the rear seat back to extend space for your children.

“Would you like me to drive, James?” asks the Siri voice command system.

“Yes,” you reply.

The journey begins. Time to put the finishing touches to the kids’ school homework, with a maths test still to be completed and a poem that needs writing. Thank goodness for the 15 extra minutes in the car.

News headlines are screened via a subscription media service. As you scan them, the Volvo’s autonomous driving system continuously streams data to servers and downloads information from other vehicles, enabling the car to recognise and react to live traffic conditions on the route.

With the school run done, it’s off to your first work meeting of the day.

“Paul Rushton is ready to video call with you, James,” says Siri. “Would you like to go ahead?”

“Sure,” you reply.

The news fades out and the call begins. It’s an opportunity to tie up all loose ends before you meet with a supplier for the day. Siri takes notes and action points for both parties to follow up on.

The two-hour journey is smooth and drama-free. Unlike older cars with the early autonomous driving software, your modern Volvo effectively talks with other vehicles. As a result, if cars encounter problems further along your route, the Volvo’s navigation system is fed the relevant information and adjusts its route, or speed, accordingly. And although the traffic is dense, the flow is smooth.

All new cars sold must be fitted with the same autonomous technology; made mandatory by the EU a couple of years ago. An estimated 93% of accidents used to be caused by driver error, so removing the driver from the process was inevitable. Consumers responded enthusiastically to cars that were safer, too. Owners of older cars were encouraged to trade them in for recycling by a £5,000 scrappage scheme.

In another five years’ time, the talk is that the technology will have proved itself robust and reliable enough that all traditional driving controls – the steering wheel, pedals, gearshift and mirrors – will be removed. It’s the end of the driver.

Later the same day, as your supplier meeting draws to a close, you glance out of the window. There’s a stranger loitering by your car. It would have looked suspicious five years ago, but he’s the man from Morrisons. After the supermarket woke up and embraced online shopping, it became the first to deliver shopping to customers’ cars.

A cooler is built into the car’s boot, powered by solar energy generated from the panoramic glass roof. A code was generated when you ordered your shopping, which gives the supermarket a one-off key code to access your car using a telematics app which communicates with the Volvo On Call software.

On the way home, you ask Siri to find a good recipe for sea bass. This triggers a promotional offer, based around your search request and the route home, to stop at a Secret Cellar and take advantage of a unique 20% discount on six bottles of Sauvignon Blanc.

“Would you like me to divert to take advantage of this offer, James?” asks Siri.

“Too right,” you reply. It’s been a long day, after all. And why not add a movie rental to the cloud while you’re at it, chosen from preview clips played while the car drives you home.

Arriving home, your plug-in hybrid Volvo parks itself on the contactless charging station and Siri reminds you to take the shopping from the boot, while sending a recipe to the cloud that you’d asked it to search for, ready to be pulled down to the kitchen’s tablet when the ingredients are unpacked and the wine is opened and poured.

How realistic is this scenario?

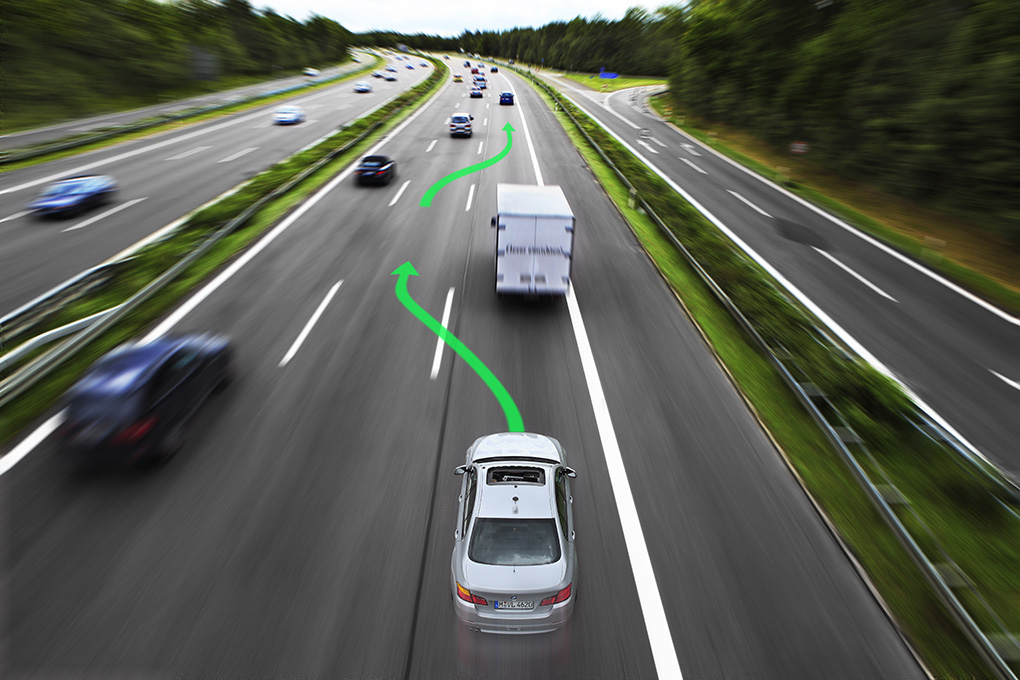

Highly realistic. This week, Carlos Ghosn, CEO of Nissan, announced the company’s cars would be partly autonomous by 2016, with the ability to drive themselves in stop-start traffic and park themselves. By 2018, he stated that the latest models from the Japanese manufacturer would feature “multiple lane controls”, which means they’ll be able to change lane on the motorway and negotiate a cross-roads autonomously.

Is Nissan being optimistic?

No, says Vincent Charles of Continental. The German car component supplier manufactures the many components that are required to make cars that are capable of driving themselves. He says his company believes fully autonomous cars will “comfortably be technically possible by 2025”. He adds that Continental expects its Advanced Driver Systems Business to grow to a £792m (1 billion euros) turnover in the next three to four years.

Who will manage how cars communicate?

Continental has formed partnerships with Cisco and IBM. “Cars can potentially stream a huge amount of data – gigabytes – to servers, which is too much,” says Vincent Charles. “The information needs to be filtered down to what’s relevant and then compressed, which is where CISCO and IBM have expertise.”

Other car makers, such as Ford, have formed partnerships with Microsoft and, more recently, Blackberry. Google and Apple have both developed operating systems for cars.

Will I be pestered in my connected car?

That depends on whether you opt in to be pestered, says Adam Singer, Chair of the British Screen Advisory Council. The BSAC represents media organisations including the BBC, ITV, Sky, Vodafone, Google, Warner Brothers and the British Film Institution. Singer believes the automotive industry is in a position similar to the dawn of multi-channel television and the days of Sky going live in 1992.

“There will be multiple players but we need one powerful platform – a gatekeeper,” he says. “The economics of the living room apply to the car. The value that connectivity confers is going to set the investment trajectory of the automotive industry for the next 20 years.”

What about legislation and insurance?

“We’re still a long way from working out the implications for insurance,” says Dave Meader, the head of underwriting at Direct Line Group. Meader says there need to be working parties formed to cover road traffic legislation in the UK.

“Take the definition of an RTA [road traffic accident] which says you must be in control of the vehicle. If you’re watching a film on your Google Glass, and the car is doing the driving, who is responsible?”

It will take the insurance industry years to build an accurate picture of the reliability and effectiveness of autonomous technology, so that it can assign a rating system to the different makes and models of cars, just as it does now to allow it to calculate premiums as accurately as possible.