Driving.co.uk’s greatest minds in motorsport ahead of the Goodwood Festival of Speed 2022

Heavy on Brits, and who can blame us?

THE THEME of this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed (June 23-26) will be “The Innovators — Masterminds of Motorsport”, focusing on the technology behind all kinds of racing cars from the earliest Edwardian machines to the wind tunnel-honed and electrified brutes of today.

The festival will celebrate “the technical landmarks that have seen the racing automobile develop from crude behemoth to space-age projectile.”

According to the owner of the Goodwood estate and host of the Festival of Speed, the Duke of Richmond:

“Just as race-inspired innovations such as four-valve engines, monocoque chassis and turbocharging have shaped the past and present of the cars we drive in the real world, so electrification, autonomy and other new technologies — the development of which is accelerated by the white heat of competition — will have a profound effect on the future of personal mobility.”

With those august words in mind, we’re taking a look at some of those masterminds of motorsport — the geniuses and talented engineers behind some of motor racing’s most marked innovations.

It’s a Brit-focused list for sure, as, for a variety of historical and cultural reasons, Britain has had an outsized influence on the world of motorsport since the Second World War, an advantage it retains to this day.

Ferdinand Porsche

Ferdinand Porsche won the Exelberg Rally in Austria in 1901 driving a front-wheel-drive version of the world’s first petrol-electric hybrid vehicle, a Lohner-Porsche of his own design.

If that wasn’t enough to earn him a place in the automotive history books, a spell with Daimler in the 1920s saw him design the practically unbeatable supercharged Mercedes SSK series of sports cars, which, in 1931 alone, won the Argentine Grand Prix, German Grand Prix and Mille Miglia.

While a close association with the Nazi party in the 1930s tainted his legacy, even some of the vehicles he designed in that period such as Auto Union’s mid-engined grand prix cars and the Mercedes T-80 land speed record car were technically brilliant. That they became projections of the Third Reich’s aspirational image of itself is a shame.

Owen Maddock

Maddock is probably the most brilliant motorsport engineer of whom few have ever heard. While engineers such as Porsche had built mid-engined racing cars before, it wasn’t until the Cooper Car Company adopted the then-weird curved tubular chassis designs of its engineer, Owen Maddock, that the potential of the design became clear.

Maddock and Cooper’s design for a mid-engined sports car evolved into race-winning Formula 2 machine, and in 1959 Jack Brabham (became the first driver to win a Formula One world championship driving a mid-engined car, the Maddock-designed Cooper T51 (see Brabham in the car above, at the 1959 British Grand Prix).

Single seater racing would never be the same again.

Aurelio Lampredi

Aurelio Lampredi worked at Ferrari from the late 1940s designing a series of beautifully-engineered, naturally-aspirated V12s that saw use in successful sports and racing Ferraris of the period. Lampredi followed up the V12 with a twin-cam four-cylinder that was also raced extensively in both sports cars and at Formula 1 level.

In the mid-1950s, Lampredi moved to Fiat where he would work until 1977. While there, he designed the outstanding Fiat Twin Cam engine that would be used not just in peppy Fiat road cars but, in modified form, rally legends such as the Lancia 037 (above) and Delta Integrale, as well as the Fiat 131 Abarth.

Colin Chapman

Between 1962 and 1978, Lotus, under the aegis of Colin Chapman, won seven F1 constructors’ titles, six drivers’ championships and the Indianapolis 500.

The Chapman-designed Lotus 25 was the first fully-stressed monocoque chassis to appear in F1 and was a phenomenally successful racing car in the 1960s with Jim Clark behind the wheel.

Chapman was an early proponent of aerodynamics in F1, a technical avenue that eventually resulted in the 1977 Lotus 79, which made extensive use of ground-effect to increase downforce rather than relying so much on wings.

His mantra at Lotus Cars was “Simplify, then add lightness”. A genius of engineering by any standards.

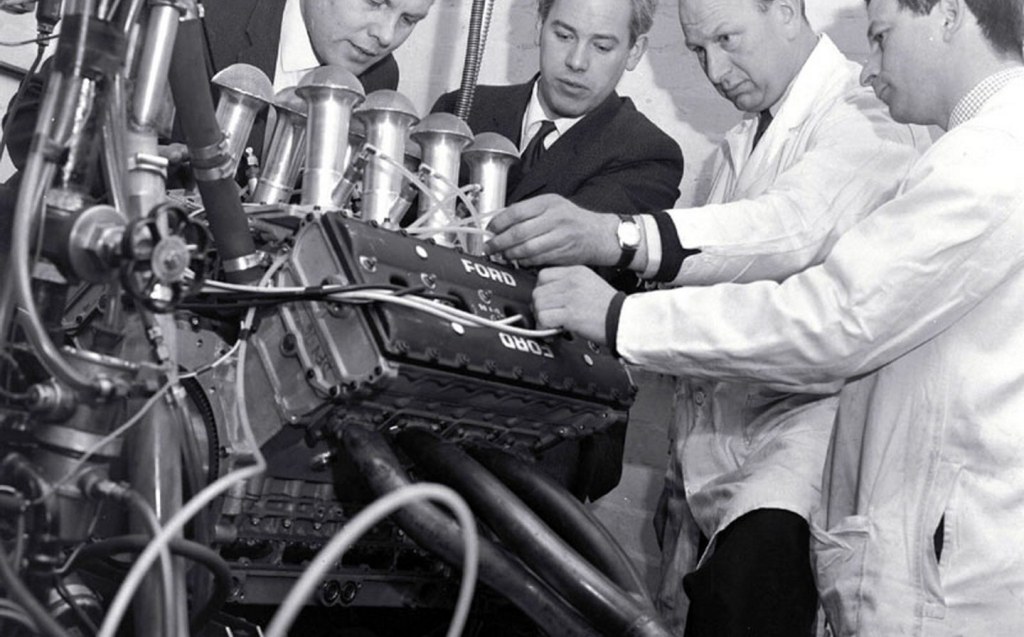

Mike Costin & Keith Duckworth

Engineers Mike Costin and Keith Duckworth left Lotus to found their own design consultancy firm, Cosworth, in 1958.

Their old boss Colin Chapman eventually persuaded Ford to fund development on one of Cosworth’s new designs for a 3-litre V8 racing engine, the Cosworth DFV.

Following its Lotus Grand Prix debut in 1967, the DFV became one of the most successful racing engines of all time, helping to win 12 F1 drivers’ championships between 1968 and 1982, as well as 10 F1 constructors’ titles for Lotus, Matra, Tyrell, McLaren and Williams.

On top of that, DFV-powered cars won Le Mans twice and DFV variants would win the Indy 500 ten times.

Frank Costin

While his brother Mike was the “Cos” in Cosworth, Frank Costin was the “cos” in Marcos, the low-volume maker of glass-fibre- and wood-bodied sports cars, some of which could best be described as rather awkward-looking. But there was a reason behind some of those challenging aesthetics — aerodynamics.

An aircraft engineer at de Havilland by trade, in 1955 Frank Costin was approached by his brother to design the body for a new Lotus racer, the Mk8. This was the beginning of a relationship with Lotus that would see the company’s racing car bodies honed to aerodynamic perfection.

Further commissions for Vanwall and Maserati Grand Prix resulted for Costin, though, due to his distaste for business and publicity, he never achieved the fame of other aerodynamicists such as Jaguar’s Malcolm Sayer, preferring to remain out of the limelight.

Instead, he designed technically interesting, aerodynamically slippery and slow-selling sports cars such as the Costin Amigo.

Eric Broadley

After unsuccessfully dabbling in F1 designs, Eric Broadley turned his attention to GT racing. His Lola Mk6, though not especially potent on track, featured some of the most advanced technology of the time including an aluminium monocoque and the big Ford V8 as a stressed part of the chassis, some four years before Lotus successfully tried the same thing in its F1 cars.

Ford noticed the Lola and decided, collaborating with Broadley, to use it as the basis for its new GT40. While the Ford sports car based on Broadley’s designs would go on to win at Le Mans four times between 1966 and 1969, the mercurial Broadley quit the project after 12 months.

He moved on to design the Lola T70, a futuristic-looking racer that would go on to score a one-two finish at the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1969.

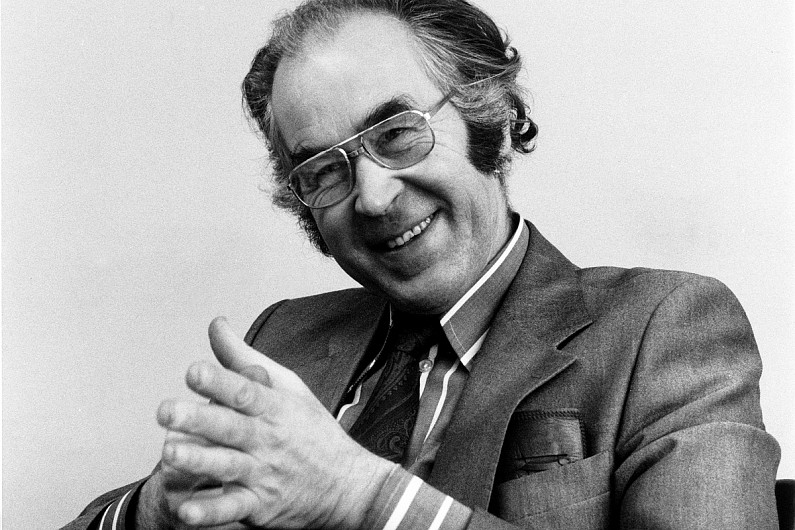

Gordon Murray

The South African-born Murray moved to England in 1969 hoping to find a job at Lotus, but soon found himself at Brabham designing a string of extraordinarily-advanced world championship-winning F1 cars.

In the late 1980s, he joined McLaren, initially working on its racing cars before going on to head McLaren Cars, designing the McLaren F1, long the fastest road car in the world and one that many consider to be the greatest road car of all time. In its GTR racing guise, the McLaren F1 took victory at Le Mans in 1995.

Murray currently heads Gordon Murray Automotive, a company responsible for similarly extraordinary models such as the T.50 and T.33 supercars, as well as having a keen personal interest in small, light vehicles, designing machines as diverse as the 385kg Light Car Company Rocket and GMA T.25 electric microcar.

Adrian Newey

Adrian Newey’s career has seen him design one successful racing car after another. Before he was 30 years old, in the mid-1980s his IndyCar designs for the March team won the 1985 and 1986 Indy 500, as well as the overall Indycar championship.

Switching to F1 in 1988, between 1991 and 1996, Newey designed the dominant Williams cars that won five world championships between 1992 and 1998 in the hands of drivers such as Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost, Nigel Mansell, Damon Hill and Jacques Villeneuve.

A spell with McLaren followed between 1997 and 2005, but Newey then joined Red Bull Racing, his designs helping to earn it four constructors’ championships between 2010 and 2014 with Sebastian Vettel and Mark Webber behind the wheel.

Newey remains at Red Bull Racing, having overseen the design of the Honda-engined car that gave Max Verstappen the drivers’ championship in 2021. The man doesn’t seem to know anything other than success.

Tweet to @ST_Driving Follow @ST_Driving

Related articles

- If you liked reading Driving.co.uk’s list of the greatest minds in motorsport, you may want to check out how the 2021 F1 season went down to the wire in Abu Dhabi

- Did you read our guide to the F1 Halo?

- Track record: F1 2021 in pictures

Latest articles

- Seven great automotive events to visit this summer, from F1 to art and champagne

- Watch new Porsche 911 GT3 smash Nürburgring record for manual cars

- Skoda Elroq 2025 review: Czech carmaker can’t seem to miss with its electric family cars

- Five best electric cars to buy in 2025

- Should I buy a diesel car in 2025?