Rural Britain facing ruin as independent petrol stations bite the dust

The drip, drip, drip of life draining out of the British countryside

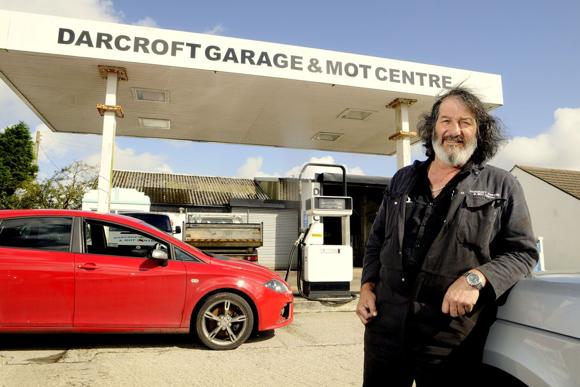

UNTIL he was forced by collapsing oil prices to close his fuel business, Barney Barnes was typical of the unsung rural filling-station owners who helped to keep the British countryside rolling along. Positioned handily on the A30 across Bodmin Moor, Darcroft Garage was an oasis for traffic travelling across the empty spaces of the southwest. Locals going about their business, holidaymakers en route to the Cornish coast, coaches carrying children on field trips, midwives and district nurses, farmers and vets — Barnes has filled them all up.

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

A stickler for tradition, he still cleaned the windscreen of every vehicle that stopped. Then oil prices fell off a cliff — plunging by 40% in the year to April — and after 13 years at the pumps, Barnes was forced to hang up his nozzle. Darcroft Garage remains open for car and truck maintenance and MoTs, but its days of selling fuel are over.

Like the estimated 4,000 small filling stations that have thrown in the towel since 2000 — about 60% of all the independents in Britain — it was unable to cope with a lethal combination of oil companies, taxes and supermarket price wars. “It’s a pity,” says Barnes, “but the days of the small standalone fuel retailer are numbered.”

When Darcroft Garage began dispensing fuel to motorists, petrol was one shilling and eight pence a gallon, and there was no tax on it. That was in 1924. This year, when Darcroft Garage dispensed its last petrol, it cost £1.23 a litre (£5.60 a gallon), of which just under 70p a litre was tax and duty, and it seemed that just about the only person who wasn’t making any money out of the petroleum business was Barnes.

The Petrol Retailers Association (PRA) says that by the end of this year there will be about 8,500 filling stations in Britain, against 13,000 at the turn of the century

While the motorist’s joy is unconfined as fuel prices continue to fall, the retail market is in the throes of a revolution that will affect us all, and not entirely for the good. Small independents are going under and oil companies are abandoning their filling stations wholesale. On the other hand, the independents who can afford it are ploughing millions into “retail experiences” where fuel sales form part of a mutually supportive complex of shops and where petrol is often little more than a lure to attract customers.

Behind all this upheaval stand the big four supermarkets, ever undercutting on price. But if you’re out in the sticks with no fuel-dispensing supermarket close by and not enough trade to attract a “retail experience”, the future looks bleak. Entire communities, some on busy routes, will soon have no nearby fuel source, and the consequences could be far-reaching.

Close to Darcroft Garage, Bodmin has two supermarkets whacking lumps out of each other on petrol prices, and it enjoys some of the lowest fuel costs in the country. Last week diesel was selling at £1.06 a litre.

Small independents who say they can’t even buy wholesale at those prices have their backs to the wall. Darcroft continued to sell diesel after it stopped selling petrol because supermarket sites are not easily accessible to coaches and HGVs, but eventually even that made no sense. “We were left with no alternative but to close the pumps,” said Barnes.

The Petrol Retailers Association (PRA) says that by the end of this year there will be about 8,500 filling stations in Britain, against 13,000 at the turn of the century. Of that original 13,000, 7,000 were independent, and 4,000 of those have closed.

Barney Barnes has had to stop serving fuel at his garage in Cornwall and fears the days of independent fuel retailers are numbered (Stuart Clarke)

The story is one of massive overheads and razor-thin margins. A 40,000-litre tanker load will cost £12,000, plus £28,000 in tax, which often must be paid to the government on delivery.

Customers pay mostly by credit or debit card, which means a delay of a week or 10 days before the money comes in. The tanker visits to schedule, not to order, so cash flow problems can become acute.

Brian Madderson, the PRA’s chairman, says: “Depending on circumstances, the retailer is making between 0.5p and 8p a litre, and most would average 4p to 5p over the year. But overheads are never steady — business rates are going up, and the ‘living wage’ is something that will make the difference between survival and closure for some filling stations.

“At this rate all we’ll be left with are supermarket forecourts — they now have over 45% of the market — and motorway or A-road service stations, but local filling stations are vital. Supermarkets use petrol as a loss-leader to attract customers into their stores. People who drive long distances to take advantage of this no longer shop locally, which has a further impact on remote communities. It will take government intervention to ensure that smaller petrol stations survive as a broad network for the benefit of every motorist.”

The government seemed to recognise the problem when it allowed a 5p-a-litre reduction in fuel duty under the rural fuel rebate, originally introduced in Scotland but extended to cover the whole of the UK from May 31 this year.

“People who drive long distances to take advantage of cheap supermarket fuel no longer shop locally, which has a further impact on remote communities”

The rules for qualification are so tightly drawn that in England only a tiny proportion of filling stations qualify, in four postcodes in Northumberland, Cumbria, North Yorkshire and Devon. In fact, only one filling station in Britain south of Leeds qualifies, and that is Barbrook Garage in Lynton, Devon.

The owner, Lesley Goodman, has seen fuel sales quadruple to about 150,000 litres a month because she has been almost able to match supermarket prices, and people in Lynton no longer drive to Barnstaple or Minehead for fuel, or anything else.

“We have to pass on the entire rebate to the customer, so the advantage to us is in the increased footfall in our shop,” Goodman says. “But the advantage to this community of 1,600 people is incalculable. Money that would otherwise flow out to the supermarkets now stays in Lynton. It costs the taxman very little, but it does our community a power of good.”

Madderson is recommending to the government that big supermarkets should not be allowed to sell fuel below cost price; nor should they employ deep discount tactics such as cheaper petrol if large sums are spent in their stores.

Madderson says: “If HM Revenue & Customs does not appeal, most filling stations will get 28 days’ grace, which should take some of the pressure off cash flow. But more direct government action is needed if small and remote communities are not to be isolated further.”

Even if the government offers further help to independent stations, it will be too late for Barnes. The costs of restarting would be prohibitive. “It’s hard to see how the little man can make a living selling petrol,” he says. “When all the small filling stations are gone, we’ll see how long it takes supermarkets to decide they don’t need to discount any more.”

His former customers will now have to fill up closer to home rather than en route — and clean their own windscreens.

£1 a litre in sight

Drivers filling up for the bank holiday getaway last weekend saved up to £20 a tank compared with last year, with the cheapest diesel now 29p a litre less than the average cost 12 months ago, according to figures from the AA.

Some of the cheapest fuel on sale in Britain was being pumped from an Esso station just outside Heathfield on the A267 in East Sussex last week. Diesel was 104.9p a litre, and petrol a penny more.

According to petrolprices.com, which collates fuel prices across the country, this was the cheapest petrol anywhere in Britain as Driving went to press. Some other filling stations, including the independently run Knowl Hill Esso garage on the A4 in Berkshire were matching the 104.9p diesel price.

Supermarkets are engaged in a fierce price war, too, with Tesco, Morrisons and Sainsbury’s cutting 2p a litre from unleaded and 1p from diesel.

The price of crude oil is still falling as increased production from fracking in America and oilfields in Iraq has coincided with flatlining demand and warnings of decreasing growth, particularly in China.

The question now: will fuel prices fall through the psychologically important barrier of £1 a litre, and if so, how low can they go?

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk