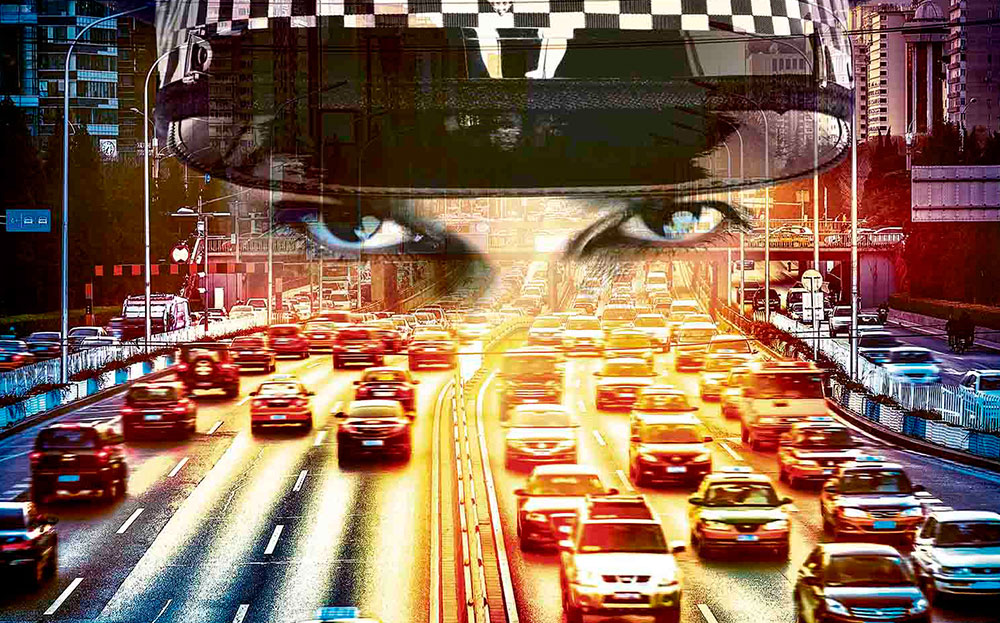

The roadside surveillance cameras tracking every journey you make

We’ve got your number, and 22bn other ones too

EVER NOTICED the discreet black boxes mounted on motorway gantries or attached to lampposts? You could be forgiven for missing them amid the forest of other devices enforcing speed limits, bus lanes, box junctions and traffic lights. But there are now about 8,300 of these black boxes dotted across the UK, including ones fitted to police patrol cars. You won’t be fined if you commit a motoring misdemeanour in front of one; they are not interested in whether drivers are speeding or jumping lights. Nevertheless, they are keeping a 24-hour watch on traffic and form part of what has been described by the government’s surveillance tsar as the densest non-military surveillance network in the world.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

Every time a car passes one of the boxes, the camera it contains takes a digital picture of the numberplate. Each image is analysed by automatic numberplate recognition (ANPR) software, which records the plate, with the date, time and location at which it was snapped. All the information is sent to a data centre in Hendon, north London.

Police can search the database by registration number. By looking at information recorded over a period of weeks, officers can build a picture of a vehicle’s owner — where they visit and when they travel, whether on a commute, a motorway drive or a shopping trip. The cameras’ locations are not disclosed by the police.

Up to 35m numberplates a day are being captured, compared with 14m a day in 2010. With an estimated 9m vehicles on the roads on any given day, that means the average car is now snapped four times. Records are kept for two years, and the data centre at present contains 22bn entries. Plans are being made to more than treble this period to seven years, which would mean that any journey made today could be retrieved in 2022 and used as evidence in court.

Britain is estimated to have 8,300 ANPR cameras, though their locations are closely guarded secrets

Privacy campaigners have sounded the alarm, warning of the threat to people’s private lives and the lack of transparency of the database. Now their concerns have been mirrored by the government watchdog, the surveillance camera commissioner, a former police chief.

Tony Porter was appointed to keep tabs on the expanding network of cameras, including ordinary CCTV. In his annual report Porter comments specifically on the apparent lack of regulation when it comes to ANPR. “There is no statutory authority for the creation of the national ANPR database, its creation was never agreed by parliament and no report on its operation has even been laid before parliament,” the report says.

Porter calls for greater transparency of the system and warns police about the possibility of legal challenges to its use for mining data about private individuals, which “can be far more intrusive than communication intercepts”.

Speaking to The Sunday Times last week he went further, saying he was opposing proposals by the police to increase from two years to seven the length of time they can store numberplate data.“I do not consider the evidence at the moment shows there is a necessity to keep this data beyond two years.

“I recognise the potential value, but you have also got to recognise that society might not tolerate the state having that type of information for years on end on a ‘just in case’ basis.”

So what is ANPR, how does it work and how did it grow to become — in Porter’s words — “one of the largest data gatherers of its citizens in the world”?

ANPR technology started as a useful tool for police about 10 years ago. Patrol cars fitted with the system can quickly check the identity of any driver by automatically matching a vehicle’s registration number with records held by the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and the Motor Insurers’ Bureau. If the vehicle is identified as wanted, untaxed, uninsured or without a valid MoT, or if the owner is a criminal suspect, an alert sounds and officers will pull the car over.

Since 2006, however, the details of any numberplate recorded, regardless of whether or not the driver has been stopped, have been sent to a database known as the National ANPR Data Centre, a £32m computer system in Hendon.

Today every one of the 43 police forces in England and Wales has the cameras and contributes to the database, which is run by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC). All 43 constabularies have access to the records, as do the Ministry of Defence, the National Crime Agency and HM Revenue & Customs.

By searching for a single registration number, officers can call up every time a car has been recorded in the past two years, potentially locating a vehicle at a certain time on a specific day. Police investigating a chain of burglaries, for example, could call up a list of cars recorded in the local area at the time each crime took place to find suspects.

Officials say the system is an essential part of modern policing, which has helped solve serious crimes and provided crucial evidence to convict criminals.

ANPR is about collecting information that’s 99% on innocent people and people who aren’t likely to be suspects

Privacy campaigners say the data collected and stored does not relate only to criminal suspects. “The ANPR database is about collecting information that’s 99% about innocent people and people who aren’t likely to be suspects,” says Richard Tynan, chief technologist at the human rights campaign group Privacy International. “We are constantly told by politicians that this is only for suspects and terrorists, but there’s no getting around the fact that they are capturing massive amounts of data on the record of people’s cars, which means they can start to do very crude tracking of vehicles around the country. The collection of the information in the first place ought to require suspicion before it’s even ingested into the system.”

Tynan argues that the system is open to abuse by police, who could use it to profile certain types of lifestyle. “The fear is that big data and machine learning could be applied to, for example, figure out the pattern of life for individuals and to have people brought under suspicion simply because their pattern of life or movements match some profile of a terrorist suspect or criminal,” he says. “Just living your life is sufficient to bring people under suspicion.”

The use of ANPR is governed by a code of practice issued in 2012 that applies to all surveillance cameras, including CCTV. It requires that authorities follow 12 principles when using the data, including transparency, proportionality and accountability. Access to the database is also strictly controlled, according to the government.

“The use of ANPR and access to the data it collects is subject to a stringent set of safeguards,” says the policing minister, Mike Penning. “The government aims to ensure that the public can be confident that surveillance camera systems in public places are there for their personal protection.”

Police also defend its deployment. “ANPR has been used for over a decade and is a vital tool in both the prevention and the detection of crime,” says Assistant Chief Constable Paul Kennedy, who is in charge of the system at the NPCC.

“It enables police to understand local crime patterns and has resulted in the arrest of some of the country’s most prolific and dangerous criminals. Police forces recognise their responsibility to protect people’s privacy too. ANPR is used proportionately.”

Proportional or not, the use of ANPR is only going to grow. A recent report by Transparency Market Research said the value of the global ANPR market is expected to rise from $416m (£275m) in 2013 to more than $1bn by 2020, with Britain the biggest market in Europe.

So next time you see a discreet black camera by the roadside, remember that your journey is being monitored. That may make you feel safer. And, after all, if you have done nothing wrong, then you have nothing to fear. Have you?

For their eyes only: the data centre far more secret than Bond’s HQ

You can see MI6’s headquarters in high-definition detail in the latest James Bond film. GCHQ has taken Sunday Times journalists for tours around its doughnut-shaped building. And we’ve all heard about the brown road sign paradoxically pointing drivers towards the “secret nuclear bunker”.

But there’s one building in Britain that’s still cloaked in great secrecy. Even the colour of its external walls is protected information. The National ANPR Data Centre is located within the Metropolitan police’s Peel Centre in Hendon, north London, behind a long fence, monitored by CCTV.

The site is currently being redeveloped to provide “new facilities fit for the purpose of modern policing” and a dedicated website shows glossy computer-generated images of how it will look. But there’s no sign of the data centre, which holds 22bn records of British vehicles and the journeys they have made in the past two years.

We asked the Home Office for a guided tour, in which they could explain how our data is kept secure against physical attack and hacking, and who has the right to see the information. It said no, so last week we visited the site, identifying ourselves as journalists from The Sunday Times.

A receptionist at the heavily secured main gate of the police compound said we would not be allowed inside, so we asked where the data centre was or — failing that — for a description of the building. “I’ve been told not to divulge any information,” said the receptionist, who called a security guard.

The guard asked about the identity of the Sunday Times photographer waiting outside reception. We were happy to co-operate and prove that our intentions were simply to find out more in general terms about what records were stored.

We noticed a plan showing the police buildings, but the data centre appeared to be unmarked and we were told to speak to the Home Office for more information. We agreed to do that and left the premises.

In a speech to police chiefs last month the government’s surveillance camera commissioner, Tony Porter, warned that the only way to keep the public happy about the vast amount of information being gathered through ANPR was transparency. Perhaps that message has yet to filter through.

Dominic Tobin

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk