Welcome to California's hydrogen highway

A clean future is a gas, gas, gas

THE LOUDEST thing you’ll hear from behind the wheel of a fuel-cell car driving up the Californian coast is the hum of the tyres on the concrete interstate stretching north from Los Angeles towards Silicon Valley and San Francisco.

There’s no rumble of a big American engine from under the bonnet, no growl from the exhaust. These are things of the past. The only emission this hydrogen-powered Hyundai Tucson produces is water — so pure you can sip it from the tailpipe. Welcome to the future. It’s mute.

Car makers have been promising us the benefits of hydrogen power for years, but only now are the claims convincing.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

What has changed? Not fuel cells — they’re fundamentally unaltered since 1842 when William Grove, a Welsh scientist, came up with the idea of generating electricity from hydrogen gas. His idea has been refined and fuel cells are now cheap and efficient enough to power silent electric motors in cars such as the one I’m driving.

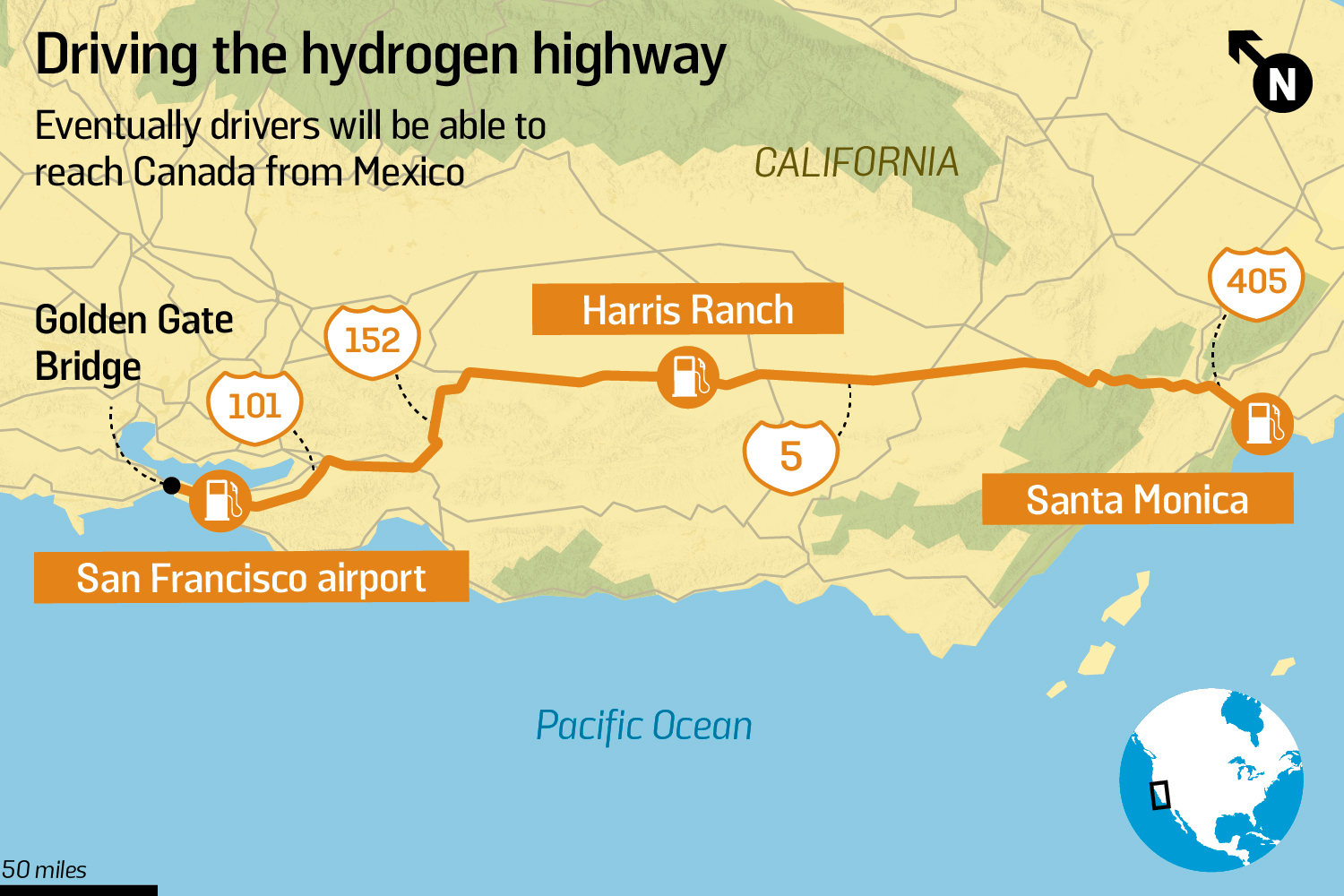

But the most exciting progress is in the development of the infrastructure that will allow drivers to refuel. The “hydrogen highway” is a string of planned refuelling stations along the Californian coast that is a test bed for the new technology.

Arnold Schwarzenegger launched the highway with great razzmatazz in 2004 when he was “governator” of California during an interlude between terminating people on screen. As well as reducing pollution, hydrogen offered an end to the dependence on imported oil and an example that other gridlocked countries including Britain could follow.

The project collapsed along with the Californian economy in 2008. But now, like the Terminator, it’s back. Governor Jerry Brown, successor to Schwarzenegger, has pledged $20m (£13m) a year for the next decade.

The state authorities in California want to see at least 1.5m hydrogen, electric and plug-in vehicles on the roads by 2025. That means building 100 new stations, bringing most Californian drivers within range of a fuel stop.

In two weeks, the first phase of the hydrogen highway — a 400-mile stretch — will be complete when a station halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco opens. Last week, with special permission, The Sunday Times completed the journey in a fuel-cell car, the first media organisation to do so.

The Harris Ranch refuelling stop near Coalinga is the crucial missing link between stations in Los Angeles and the Bay Area of San Francisco. Hyundai — one of the big companies leading the charge into hydrogen — says the stop could jump-start the technology in California and mark a tipping point for its adoption elsewhere, including Britain.

In America, the company has leased out about 85 cars, including the Tucson I’m driving. Toyota, another hydrogen pioneer, has put 30 Mirais on the road since deliveries began last month. Both admit there is a long way to go. “We know from all the interest we get that drivers want to buy them — and many more will when the refuelling network is in place,” says Derek Joyce of Hyundai Motor America.

My car costs $499 a month to lease (as in Britain, most new cars in America are bought on lease). To encourage drivers to adopt the technology, Hyundai offers free fuel for the first three years, and Toyota three years’ or $15,000-worth of free fuel, whichever comes first.

Will drivers take the bait? On my way up Interstate 5 (I-5) from Los Angeles, the most remarkable thing about this car is how unremarkable it is. It drives like any petrol-electric hybrid. The controls are as you would expect in a mid-size SUV. There’s a fuel gauge showing the hydrogen level and a gearbox setting for generating electricity from the braking effect of the motor when coasting.

The fuel cell under the bonnet is fed from a tank under the boot floor with pure H2 — the same stuff that powers the sun. The tank looks too dull to carry an exciting fact like that but it’s the product of some advanced engineering that allows hydrogen to be stored at pressures of about 700 bar (10,000psi) — about 3½ times that of a typical scuba tank.

I keep a careful eye on the fuel level. I filled up in Santa Monica, west Los Angeles, and if I run out of gas I’ll be forced to call a tow truck to take me back there. It won’t be a pleasant wait in the roadside heat with lorries thundering past.

Strictly speaking, there’s no mpg figure — the Tucson will do about 265 miles on a full tank of hydrogen (5.6kg of gas). The “equivalent” figure, taking account of the hydrocarbons used in hydrogen production, is 50mpg.

By the time I arrive at Harris Ranch it’s dusk. I’ve travelled just over 180 miles and according to the dashboard readout there’s 83 miles still left in the tank — a comfortable margin. I’m met by Joel Ewanick, the founder of FirstElement Fuel. His company built the refuelling station. I point out that mile for mile, hydrogen is three times as expensive in America as petrol — it would be roughly on a par with petrol prices in Britain where fuel is more highly taxed.

Ewanick says that will quickly change with economies of scale. “Within five or six or seven years you’re gonna find the cost of hydrogen cheaper than a gallon of gas here in the United States. That will increase the adoption rates of these cars exponentially,” he says. “People will start saying they’re cheaper to fill and they go further and they’ve got zero emissions, and I’m no longer relying on foreign oil.”

Hydrogen cars also score over their pure electric counterparts because the refuelling experience is familiar. You pull up to a pump, connect a hose (the nozzle forms a seal) and it takes just a few minutes to fill the tank with gas.

Just opposite the new hydrogen pumps are charging points for Tesla electric cars and a station for Tesla drivers in a hurry, who opt for a quick battery swap. The cost is $80 for two swaps and each takes about five minutes, giving an each-way range of 270 miles. My hydrogen fill takes the same amount of time, and costs $50.

Can the two technologies — battery electric and hydrogen electric — exist side by side?

Not according to Elon Musk, the chief executive of Tesla. He has scoffed at fuel cells — calling them “fool cells” and a waste of time. Hydrogen is an inefficient way to store energy, he says, and transporting it is fraught because of its potential combustibility. Advocates point out that hydrogen cars and filling stations have been rigorously tested and are as safe or safer than petrol. But the remarks have given ammunition to critics.

The war of words between battery and hydrogen enthusiasts is likely to escalate. Toyota, the world’s largest car maker, was an early partner with Tesla, investing $50m in the California-based company and co-operating on a battery-powered version of its RAV4. Now Toyota has stopped production of the electric RAV4 and has shifted its allegiance to fuel cells. It is an investor in FirstElement.

Others are climbing aboard. Honda unveiled its fuel-cell Clarity in October and says it will be available for lease next year. Mercedes-Benz has promised a fuel-cell vehicle by 2017 and GM, Ford and Nissan are testing prototypes.

Replenished with hydrogen, I continue up the I-5. At truck stops, the car, emblazoned with the words “hydrogen” and “zero emissions”, attracts interest. Yet nobody I meet has heard of the hydrogen highway. “I guess we’re just too much in love with gasoline cars,” says Todd Fairman, who describes himself as a gold prospector who needs a big V8 pickup. “Maybe one day, when oil is as scarce as gold, I’ll make the switch.”

I reach the last fuel stop near San Francisco airport with more than 100 miles of gas still in the tank. This station — also due to open next month — is another crucial link in the highway.

Then it’s only a short hop to my final destination— the Golden Gate Bridge. Hipsters on the Embarcadero love the idea of zero-emissions technology and are astonished to hear Schwarzenegger was hydrogen’s chief advocate. “The Terminator guy? Man, I thought he just blew people away. I didn’t realise he was, like, a green dude.”

Slow road ahead for UK hydrogen

Britain’s hydrogen highway was meant to be the M4. Announced in 2010 by Peter Hain, then the Welsh secretary, the vision was to install filling stations along the motorway in south Wales, the start of a chain that would eventually run from Llanelli to London.

The first filling stations were due to be installed “as early as 2015” but the planned road of the future has not materialised. The only hydrogen filling station near the motorway is at Honda’s Swindon factory.

There are only three other hydrogen filling stations in Britain: one in Rotherham, one at Heathrow and one in a Sainsbury’s car park in Hendon, north London. Although they are technically open to the public, owners of hydrogen cars must set up an account, undergo training and obtain an access code to use them.

Analysts predict filling stations will slowly spring up across the country (last week planning permission was granted for a station in east London) linking towns and cities, so drivers will not be restricted to a single stretch of motorway. By 2020, the government predicts about 65 filling stations will make nationwide long-distance travel possible on common routes.

The government, which has pledged £6.6m of funding, claims it is “positioning the UK to be a lead market for the introduction of hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles”. Only Hyundai has a fuel- cell car commercially available here: the iX35 — the equivalent of the US Tucson — can be bought for £53,105. Toyota says the Mirai is coming next year.

Also read:

- The future of hydrogen filling stations in Britain

- Car of the week: Toyota Mirai

- First Drive review: 2015 Hyundai ix35 Fuel Cell

- Driving Green: What are hydrogen fuel cell vehicles?

- Honda FCV hydrogen fuel cell car ready for launch in 2016

- Hydrogen cars clean up as Honda opens solar-powered filling station

- Test your knowledge: When did Honda unveil its first hydrogen car prototype?

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk